Easy Really Difficult Steps to Creating a Patriarchal Pagan Group.” My purpose is not to make women feel responsible for male dominance or poor behavior, but to frame the goals of feminist spirituality as natural outcomes that take consistent effort to subvert.1) Place no prerequisites on male participation. Women are often the majority or the exclusive members in a new experimental enterprise, spiritual or not. As soon as the effort becomes established into something viable, the men show up. While Shulamith Firestone sagely observed that “Sex class is so deep as to be invisible,” it is women – who actually experience sexism from the first day of their lives – who are more likely than men to understand that sexism can be hard to recognize. Women entering a goddess group are more likely than men to have read at least a little feminist theory, and of course they have a lived experience of women’s oppression. Men often believe that their own belief in gender equality is enough. Women, trained from an early age not to be “too demanding,” often operate out of a trust that a “nice guy” who “means well” will automatically be appropriate for group membership.2) Allow a disproportionate amount of group dialogue and decisions to be guided by men. In mixed group discussions women talk only about a quarter as much as men, and men perceive women as dominating the conversation when they speak more than 30% of the time. Men are more likely to seek leadership roles than women. Women need to have a secure sense of their abilities before they take on a leadership role; men not so much. Women’s hesitation to take leadership roles they may not be fully capable of makes sense when you consider the higher amount of criticism woman leaders get from both sexes. Even when women constitute more than half of the group discussion or leadership, having only a handful of men in your organization, with the majority of them in leadership roles or dominating debate, sends a message about the relative value you place on men’s input versus women’s. Sometimes this disproportionate influence of men is seen by women as beneficial, because “We need more men.” Do we? This idea needs to be examined carefully and not taken as axiomatic. The presence of certain types of men may do far more to weaken the feminist principles within your organization than to strengthen the position of women in the world at large.3) Protect men in the organization from any confrontation by women. At this stage the lioness’ job is to defend the lion from that other lioness, making his potentially hurt feelings the primary consideration. Thus when a woman confronts a man over sexism, she can expect to be attacked by a group of women who don’t agree that it was sexist or think she should have objected in a different manner or know that the gentleman in question is sensitive, gentle, “not a sexist at all” and therefore her confrontation was out of line. The man who may or may not have said something sexist is thus protected from having to dialogue and work things out with the woman who raised the objection.4) Operate out of the assumption that we are all trying to balance our “inner feminine” and “inner masculine.” The key word here is assumption. The idea that we have both male and female operating within us is a Jungian concept that keeps stereotypic ideas about women and men intact, while allowing flexibility within the individual. It is a dominant view within mainstream Western culture, and people who adhere to it often (unconsciously) enforce this view in spiritual settings. The problem is that not everyone sees humans or society in terms of “balancing the masculine and feminine.” Radical feminists, especially, do not see the world this way. Thus discussions about feminism and the goddess within spiritual organizations go nowhere because people are talking past one another.5) Operate out of the assumption that escape from patriarchy can only equal equality. This step flows naturally from the last, and it assumes that we have a clear understanding of what equality looks like – rather problematic after 5000 years of Western patriarchy. Many indigenous cultures place female councils in key decision-making roles, without harming or enslaving men. The feminist concept of matriarchy is not an inverted patriarchy with women despots. Especially in religious organizations, where women almost invariably outnumber men, it makes sense to become comfortable with female authority. It is truly amazing the steps liberal organizations will go to in order to keep power out of “too many” women’s hands. The idea of women in charge seems so much scarier than patriarchy.6) Stamp out sexism – against men! Once a patriarchal concept of equality is established, the next step is to keep the goddess in her place. She must always be balanced with a god. In some cases a goddess is never invoked without a counterbalancing male deity. Ceremonies must have a female and a male leader. There is widespread complaint about the “invisibility” of male witches or priests. The fact that there is a larger and more competent pool of women doesn’t matter: qualifications are only relevant when they keep women out of power.7) Do not allow women’s issues to have a voice or priority in your organization. It should be a no-brainer that a spiritual group honoring the goddess addresses the abysmal state of oppression that its female members endure. But if Catholics, Hindus and Buddhists can exalt a female deity while furthering women’s oppression, so can we. At this point mention of male violence, when it occurs at all, is met with assertions designed to close down discussion, such as “men are raped too.” The group goes out of its way to remind members that “men are not the problem,” sometimes even replacing discussions of patriarchy with the idea of kyriarchy, which makes women’s oppression invisible. The organization begins focusing its community service on important issues that are perceived as gender-neutral, such as ecological issues or pagan anti-defamation.8) Pretend the needs of transwomen and female-born women are identical. Women-only groups were not conceived as methods of validating (or invalidating) transwoman feelings of womanhood. One purpose of the women-only spiritual group is to work with a more homogenous female energy, which is completely changed when a male body enters the circle, no matter how that body has been changed by hormones or surgery. Another purpose of women-only groups is to tie women’s spiritual understanding with their bodies. This means celebrating menstruation and menopause, nurturing women preparing for childbirth through shared understanding, and embracing the female body in its natural state. The natural state of the female body does not just include nudity, but an acceptance of what a woman perceives to be her bodily imperfections. Being away from men, male bodies, and those with a male socialization in a female-only group gives women a chance to temporarily express themselves in a safer environment. All of these benefits of women-only groups become moot when people enter who have male bodies and male socializations, however much they may internally reject both. Understand that I am not saying that women and transwomen should never meet in groups excluding those who are male-identified, but to make this an issue of transwoman validation or invalidation obscures the purpose of these groups.9) Do not sanction any women-only groups. This is seen as a way of satisfying some transwomen who say they feel invalidated when the female-born meet even occasionally in their own groups. Feelings – not facts, goals or needs – are tantamount at this stage, as long they’re not the feelings of the female-born. The argument goes, if some women must have born-female rituals, why can’t they do them completely separate – unadvertised, unaffiliated and far away from any other pagan group? The problems with this conflict-avoidance tactic are that females cannot understand the benefits of a female-only group if they are never exposed to one, they cannot attend a female-only ritual if they do not know that it is happening, and this attitude sends a message that female-only groups are not legitimate. Born-female groups – social, political, and spiritual – are facing an extraordinary amount of abuse in their isolation. They face vandalism, attempts to shut down rented venues, and threats of physical violence. The location of female-only retreats is not disclosed until you pay your $500 or so entrance fee for a reason. Mixed pagan groups have begun denying women-born-female their First Amendment rights of freedom of religion and association. We can go to Iran and have the “right” to practice secretly in a hotel room, and we had the “freedom” to practice clandestinely in the woods during the Middle Ages.10) Develop a tolerance toward intolerable behavior. It is at this point that truly egregious behavior becomes acceptable in an organization, things like bullying or sex with students or other behaviors that clearly cross acceptable boundaries. The creed of “tolerance” is used to step around the powder keg of sexism that has developed. When sexism cannot be effectively addressed, all kinds of abuse becomes acceptable. Not coincidentally, it is usually young women who are victimized in the deteriorating situation.11) Identify your villainess. The Woman We Love to Hate plays the important function of facilitating solidarity in an unsafe environment. The villainess can be a member of the organization or a prominent figure outside the organization, or a group of women such as radical feminists or Dianics. Statements about the wretchedness of these women are repeated without elucidation or evidence, and statements, beliefs or practices are mis-attributed to them. This is a tactic that the Christian right plays with Democrats they love to hate. Thus President Obama is a Muslim socialist, and we know this because it has been repeated repeatedly. In fairness to both modern pagans and the Christian right, however, this tactic is as old as patriarchy. The classical Greeks said the Amazon tribes cut off their right breast (or was it the left?), broke the bones of male children, and practiced human sacrifice with abandon. Need I give examples of the pagan Women We Love to Hate? It’s an embarrassment of riches. Pagan organizations that have become sexist to the core need women to villify so they can cast themselves as moderate.12) Deny that your organization has a problem with women. This puts you squarely with the most conservative branches of Christianity and Islam. Enough said.I could actually keep going here, but twelve is a nice patriarchal number, what with the twelve disciples and all, and patriarchal paganism gets tiresome very quickly. The good news is that it’s not a matter of creating something different, but getting out of the way so that women’s leadership can flower. We only have to stop working so hard to re-establish and maintain patriarchal paganism.

Tag: Pagan Blog Project

Hecate and the Waterway

November 2, 2012

SourcesMonaghan, Patricia. The Book of Goddesses and Heroines. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1990.Plants for a Future. Salix alba.

Aine at Summer’s End

October 26, 2012

Matthews, Caitlin and John Matthews. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Wisdom. Shaftesbury, UK: Element Books, 1994.Matthews, John and Caitlin Matthews. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Myth and Legend. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2004.Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.

Neith and the Acacia Tree

October 20, 2012

In historical times Neith gained prominence as her city Sais rose in influence during the seventh century BCE, but Neith was probably worshiped in Lower Egypt long before dynasties or agriculture, when people still hunted for food. The crossed arrows on her crown probably originated as a hunting emblem, and may also relate to the defensive stinger of the bee and the defensive thorns on the acacia. Primarily Neith is a goddess of sustenance, engaged in the perpetual creation of life. Out of just one tree she created incense, perfume, wood for implements, seedpods for cattle, pigment binder for ink and paint, materials for embalming and food for bees, not to mention welcome shade in a hot dry climate.SourcesBarrett, Clive. The Egyptian Gods and Goddesses: The mythology and beliefs of ancient Egypt. London: Diamond Books, 1996.Clark, R.T. Rundle. Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 1959.

Review ~ Grandmother Moon: Lunar Magic in Our Lives, by Zsuzsanna E. Budapest

October 12, 2012 Grandmother Moon recently became available again through Amazon Createspace. The book is a collection of goddess lore based on the lunar calendar, a wheel corresponding to the zodiac sign for each lunation. There are thirteen sections or “lunations,” each starting with basic information about the moon followed by a contemplation about a goddess associated with this moon energy. There is information about the emotional side of the moon, auspicious activities, a few spells, and descriptions of lunar holidays. The lunar holidays are usually not European but Middle Eastern, Chinese, East Indian, Native American or Mesoamerican. Z explains, “This was my intention because these cultures have preserved their lunar calendars to this day.”Looking at the section for the upcoming new moon in Libra, October 13–15, Grandmother Moon categorizes it as the “Blood Moon.” Its herb is oatstraw and its animal is the cat. The goddess is the Egyptian overseer of truth and justice, Maat — not surprising since the symbol for Libra is the scale. This is a good time to fall in love and to decorate the home, and the energies of pleasure dominate. In keeping with this, Z offers a spell for physical pleasure. The festivals for this moon highlight the difficulties of incorporating an array of lunar calendars in a solar framework. The Jewish festival of Rosh Hashanah occurred at the last new moon and the Hindu festival of Diwali will occur next month. The full moon festivals occurred the end of September. We’ll have to look ahead to the Mourning Moon on October 29th and the festival of Oschophoria, when the full moon in Taurus will celebrate the ecstatic Greek God of the grapes, Dionysus. Sounds like a wonderful time for a party.Grandmother Moon is easy to pick up and put away, skim through and read out of order. It seems tailor-made for busy schedules and short attention spans. It has an index, which is helpful. The rituals, which appropriately focus on the emotions, can be done solo. It’s a great book for developing an understanding of moon energies.

Grandmother Moon recently became available again through Amazon Createspace. The book is a collection of goddess lore based on the lunar calendar, a wheel corresponding to the zodiac sign for each lunation. There are thirteen sections or “lunations,” each starting with basic information about the moon followed by a contemplation about a goddess associated with this moon energy. There is information about the emotional side of the moon, auspicious activities, a few spells, and descriptions of lunar holidays. The lunar holidays are usually not European but Middle Eastern, Chinese, East Indian, Native American or Mesoamerican. Z explains, “This was my intention because these cultures have preserved their lunar calendars to this day.”Looking at the section for the upcoming new moon in Libra, October 13–15, Grandmother Moon categorizes it as the “Blood Moon.” Its herb is oatstraw and its animal is the cat. The goddess is the Egyptian overseer of truth and justice, Maat — not surprising since the symbol for Libra is the scale. This is a good time to fall in love and to decorate the home, and the energies of pleasure dominate. In keeping with this, Z offers a spell for physical pleasure. The festivals for this moon highlight the difficulties of incorporating an array of lunar calendars in a solar framework. The Jewish festival of Rosh Hashanah occurred at the last new moon and the Hindu festival of Diwali will occur next month. The full moon festivals occurred the end of September. We’ll have to look ahead to the Mourning Moon on October 29th and the festival of Oschophoria, when the full moon in Taurus will celebrate the ecstatic Greek God of the grapes, Dionysus. Sounds like a wonderful time for a party.Grandmother Moon is easy to pick up and put away, skim through and read out of order. It seems tailor-made for busy schedules and short attention spans. It has an index, which is helpful. The rituals, which appropriately focus on the emotions, can be done solo. It’s a great book for developing an understanding of moon energies.

Moving & Changing: A Tree Collage

October 4, 2012Aphrodite and the Myrtle Tree

September 28, 2012

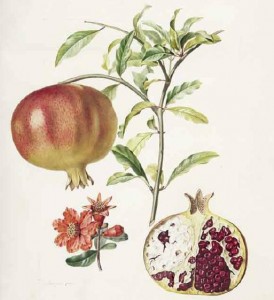

The Sacred Fruit of Persephone

September 21, 2012 The autumn equinox coincides with the start of the major ceremonies of the Eleusinian mysteries. These ceremonies, which in Greco-Roman times attracted a huge number of attendees from all over the Mediterranean, guide participants into a deeper understanding of Persephone’s descent into the underworld. There are several versions of the myth of Persephone, which is too long to explain in detail here. The gist of it is that Persephone as a maiden goddess or “Kore” is painting flowers in a meadow when the earth opens up and the death god Hades abducts her. He demands that she stay in the underworld with him as his wife and queen and refuses to let her leave. Persephone’s mother Demeter is inconsolable and neglects her duties as mother of vegetation, leaving crops to wither from lack of rain. As the earth becomes more and more parched, the gods become alarmed, and finally the chief god Zeus orders Hades to relinquish his captive. Unfortunately Persephone has eaten a pomegranate seed while in the underworld, and the laws there decree that no one who takes food in the land of the dead may return to the living. Given the urgency of the situation, a compromise is nevertheless reached: Persephone will spend four months of every year in the underworld with Hades and will spend the rest of her time on earth with her mother Demeter. From Apollodorus:

The autumn equinox coincides with the start of the major ceremonies of the Eleusinian mysteries. These ceremonies, which in Greco-Roman times attracted a huge number of attendees from all over the Mediterranean, guide participants into a deeper understanding of Persephone’s descent into the underworld. There are several versions of the myth of Persephone, which is too long to explain in detail here. The gist of it is that Persephone as a maiden goddess or “Kore” is painting flowers in a meadow when the earth opens up and the death god Hades abducts her. He demands that she stay in the underworld with him as his wife and queen and refuses to let her leave. Persephone’s mother Demeter is inconsolable and neglects her duties as mother of vegetation, leaving crops to wither from lack of rain. As the earth becomes more and more parched, the gods become alarmed, and finally the chief god Zeus orders Hades to relinquish his captive. Unfortunately Persephone has eaten a pomegranate seed while in the underworld, and the laws there decree that no one who takes food in the land of the dead may return to the living. Given the urgency of the situation, a compromise is nevertheless reached: Persephone will spend four months of every year in the underworld with Hades and will spend the rest of her time on earth with her mother Demeter. From Apollodorus:

When Zeus commanded Pluto [Hades] to send Core [Kore] back up, Pluto gave her a pomegranate seed to eat, as assurance that she would not remain long with her mother. With no foreknowledge of the outcome of her act, she consumed it… Persephone was obliged to spend a third of each year with Pluto, and the remainder of the year among the gods.

Persephone’s return to the upper world in February coincides with the lesser ceremonies of Eleusis.In addition to explaining the fallow period of the agricultural year, Persephone’s myth is believed to be an account of the merger of the Hellenic (Indo-European) pantheon with a much older one. The rape motif in the story underscores that the Hellenic takeover was a violent one that wrested power from women. In the words of Robert Graves, “It refers to male usurpation of the female agricultural mysteries in primitive times.”The pre-patriarchal Persephone was probably a triple goddess, with the maiden Kore her manifestation in early spring, the mother Demeter her mature aspect, and the queen of the underworld her death aspect. Note that Mediterranean goddesses were rarely depicted as hags or crones, even in their death aspect.Persephone’s symbols are many, but we are confining our attention here to the pomegranate. This tree, which is native to Afghanistan and surrounding regions, has been cultivated for at least 5000 years. It is probable that the fruit was traded even earlier, since pomegranates keep well and their flavor is enhanced during storage. Pomegranate trees grow easily from seed. They thrive in hot, semi-arid conditions, even in poor soil. After the pomegranate flowers, the burgeoning fruit has a pronounced crown. The fleshy red seeds are sectioned by membranes that are cavernous in appearance. The cave is a symbol of both the underworld and the womb. Red is the color of blood, the womb, and birth. Many ancient people in the Mediterranean and elsewhere painted dead bodies with the red mineral ocher to symbolize rebirth. Of course, seeds also symbolize birth, and the plethora of seeds inside the pomegranate make it an emblem of fertility.Provocative symbolism aside, the pomegranate is a useful fruit. The seeds have a pleasant, astringent taste that is not overly sweet. The seeds have long been used to treat tapeworms, and the rind can sooth irritated skin. The rind is also used to dye cloth yellow. The sacred trees of major goddesses usually have a long history of generosity to humans.

The Broom is Married to the House

September 14, 2012 In pagan imagery, the broom is not just a symbol of witches, but of wives. The Celtic goddess Brigid has among her many functions the charge of housekeeping, and her followers report that they often see her with broom in hand. Women used to leave their broom outside the front door when they left the house, as a signal to visitors that they were not at home. The ordinary broom used for household chores, as opposed to the witch’s ritual broom, is married to the house; when a family moves it is customary for the broom to remain at the house rather than being brought along to the new location.Many people are familiar with the phrase “to jump the broom,” which means to get married, and this custom relates to the broom as symbol of housekeeping and mature womanhood. The custom of jumping the broom was common on the American frontier when ordained ministers were scarce. A couple might be awaiting their second child before their marriage became official within their church, and the broom served to sanction their union until then. Broomstick weddings were also common among African American slaves, who were denied “real” marriage by slaveholders and Christian authorities. The association of brooms and marriage has antecedents in so many cultures that it is impossible to trace the origin of the custom, other than to say that it almost certainly did not originate in America.In many pagan weddings today, it is the jumping of the broom, rather than the exchange of rings or the words “I do,” that is the core part of the ceremony. The couple, holding hands or with hands fastened by ribbons, jumps over a broom lying horizontal on the ground. While in the air the spirits of the couple become joined, and when they hit the ground that union becomes sealed in the physical world. Superstitions about broom handles touching the ground suggest that in the older ceremonies the jumping broom might have been elevated or propped against something.

In pagan imagery, the broom is not just a symbol of witches, but of wives. The Celtic goddess Brigid has among her many functions the charge of housekeeping, and her followers report that they often see her with broom in hand. Women used to leave their broom outside the front door when they left the house, as a signal to visitors that they were not at home. The ordinary broom used for household chores, as opposed to the witch’s ritual broom, is married to the house; when a family moves it is customary for the broom to remain at the house rather than being brought along to the new location.Many people are familiar with the phrase “to jump the broom,” which means to get married, and this custom relates to the broom as symbol of housekeeping and mature womanhood. The custom of jumping the broom was common on the American frontier when ordained ministers were scarce. A couple might be awaiting their second child before their marriage became official within their church, and the broom served to sanction their union until then. Broomstick weddings were also common among African American slaves, who were denied “real” marriage by slaveholders and Christian authorities. The association of brooms and marriage has antecedents in so many cultures that it is impossible to trace the origin of the custom, other than to say that it almost certainly did not originate in America.In many pagan weddings today, it is the jumping of the broom, rather than the exchange of rings or the words “I do,” that is the core part of the ceremony. The couple, holding hands or with hands fastened by ribbons, jumps over a broom lying horizontal on the ground. While in the air the spirits of the couple become joined, and when they hit the ground that union becomes sealed in the physical world. Superstitions about broom handles touching the ground suggest that in the older ceremonies the jumping broom might have been elevated or propped against something.

Frigga and the Birch

September 7, 2012