The following research is related to my next book (in progress) about animal divination.

Most people are aware of the connection between lions and bees through the biblical story of Samson. The hero featured in the Book of Judges was on his way to meet his betrothed when he encountered a lion, which he killed with his bare hands. Some days later he passed the carcass and found a swarm of bees in it, and he scraped out the honey and shared it with his parents without telling them where he found it. The biblical account is quite clear on this point, perhaps to reconcile some inconsistencies in the tale, such as that honey coming from a dead carcass would not have been kosher. A kernel of this story originates in the cult of the bee goddess of Anatolia, as does the myth of Aristaeus recounted by Virgil near the start of the Common Era. Before moving back to Anatolia, let’s look at the Greek myth.

Aristaeus was the child of the huntress Cyrene, who liked to wrestle lions barehanded, and the sun god Apollo. He was fostered by myrtle nymphs, who taught him the cottage industries of olive curing, cheesemaking, and beekeeping. One day he was distressed to find that all his bees were dead or dying. He traveled to a pool of water and asked his mother what to do. She directed him to a seer, who revealed this was punishment for his role in the death of Eurydice. (This occurs in a well-loved tale that is only tangential to this story.) Aristaeus sought his mother’s counsel again, and she instructed him to build four altars to the wood nymphs and on them sacrifice four bulls and four heifers. He was then to leave the sacrificial place and return on the morning of the ninth day, bringing poppies, a calf, and a black ewe. When Aristaeus returned with these offerings, he found bees in a rotting carcass, which rose in a swarm to a nearby tree.

That Aristaeus is raised by myrtle nymphs is significant. It reveals him as a shamanic deity who travels to the underworld to gain knowledge. The myrtle tree is a symbol of love and marriage today due to its association with Aphrodite, who is remembered by most for her love goddess aspect, but myrtles in ancient Greece were used for funeral wreathes. While the flowers and even the leaves have a sweet fragrance, the sweetness was associated with death, perhaps because corpses emit a sweet odor as they decay. The idea of honeybees swarming on a dead carcass of any kind is absurd, although they do gather around the myrtle tree.

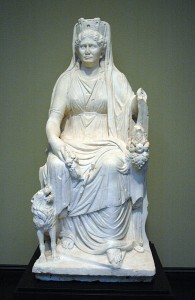

Bee and lion imagery in Anatolia goes back to before the fifth millennium. The Seated Woman of Catal Huyuk, who is flanked by two felines usually identified as leopards (which could as easily be lionesses), looks strikingly similar to classical statues of Cybele. The goddess Cybele is unmistakably enthroned between male lions.

Cybele’s myth, as told by the Greeks, starts with her arrival from outer space in the form of a meteorite. Cybele eventually falls in love with the beautiful god Attis, who returns her attentions for a time, then becomes infatuated with another. The infuriated Cybele harasses him ceaselessly until he goes insane. In remorse, Attis tears off his genitals and dies of his wounds beneath a pine tree. Cybele tearfully shrouds his body and buries it at the mouth of her sacred cave shrine, along with the transplanted pine tree.

Perhaps it was Cybele’s fiery form across the sky that first evoked the image of the fierce, fleet, destructive lion. The tormenting Cybele is the angry bee. The emasculation of Attis refers to the death of the drone after copulation. The pine is of a species found in Turkey which draws a type of aphid that sweats a sweet nectar. Bees congregate around this pine, attracted to the aphid nectar. The resulting honey is renowned for both its taste and its healing properties, and it is mentioned in Classical medical literature.

Another healing agent known to ancient physicians is the opium poppy, which strongly attracts bees. The bees gather poppy pollen granules to take back to the hive. Bees, lions, and flowers that could be poppies appear on the statue of Artemis of Ephesus, along with cattle, goats, and the animals of the zodiac. Whatever the name and personality of the mother-goddess as she was first worshiped at Ephesus, she evolved into a goddess exhibiting hybrid traits of Cybele and of Artemis, who had already absorbed many other goddesses by the time the Greeks colonized the Anatolian coast. That the bee is meant to be a significant and not a minor facet of Ephesian Artemis is demonstrated by the coinage of the city-state: deer on one side; bee on the other.

It is in Greece that art specifically linking the bee and the lion first appears, yet the association seems to have been imported from Anatolia. The swarm of bees arising from the heifer/bull sacrifice rather than from a lion is a Greek permutation of another myth. Normally bees are assumed to be linked exclusively with bulls in pictures, but we often forget cows can also have horns. Bees and cows are alike from a human standpoint, in that they provide nourishing food from their bodies. Bees like cows are normally fairly docile and allow themselves to be “herded” into a new field or nest site. But bees are like lions in that they roar, they like the sun, they hunt in an open field, they are territorial, they attack in a coordinated fashion, and (when possible) they make their home in caves.

Sources

Gough, Andrew. “The Bee” (parts I-II-III). June 2008. http://andrewgough.co.uk/articles_bee1/

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin, 1992.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Book of Goddesses and Heroines. St Paul, MN: LLewellyn, 1990.

New English Bible. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1972.