To finish up the broom series, I will share some tidbits about consecrating the magical broom (also called a besom). There is no consensus about how this should be done, but many witches believe consecration is important. Carrie Moonstone says in her Witchvox article How to Make a Besom, “Once you have finished the besom, it needs to blessed and consecrated as you would with any other magickal tool. You may dedicate it to a spirit or deity of your choice and charge it with protective energies.” As Moonstone implies, the broom is not unique in this; most magical tools are consecrated in some way.In Wheel of the Year: Living the Magical Life, Pauline Campanelli says you must first “name your broom as you would a horse.” She tells you to “anoint it with oil as you would a candle, and consecrate it in the names of the Gods:

To finish up the broom series, I will share some tidbits about consecrating the magical broom (also called a besom). There is no consensus about how this should be done, but many witches believe consecration is important. Carrie Moonstone says in her Witchvox article How to Make a Besom, “Once you have finished the besom, it needs to blessed and consecrated as you would with any other magickal tool. You may dedicate it to a spirit or deity of your choice and charge it with protective energies.” As Moonstone implies, the broom is not unique in this; most magical tools are consecrated in some way.In Wheel of the Year: Living the Magical Life, Pauline Campanelli says you must first “name your broom as you would a horse.” She tells you to “anoint it with oil as you would a candle, and consecrate it in the names of the Gods:

Besom of Birch with Willow tiedBe my companion and my guide.On ashen shaft by moonlight paleMy spirit rides the windy galeTo realms beyond both space and timeTo magical lands my soul will sailIn the company of the Crone all rideThis Besom of birch with willow tiedSo do I consecrate this magical TreeAs I will, so must it be!

Tess Whitehurst gives a detailed ritual for full moon consecration of a new broom (which is too long to quote here) in her book Magical Housekeeping: Simple Charms and Practical Tips for Creating a Harmonious Home. She uses frankincense, candle flame, salt and rosewater to consecrate the broom to all four elements. Christine Zimmerman gives a four-elements consecration here. Yvonne at Earth Witchery does not believe there is anything unique about the broom in this regard and advises to “Consecrate the finished broom as you would any ritual object.”Radomir Ristic in Balkan Traditional Witchcraft maintains that “The broom itself has magical power and it does not require consecration.” I myself lean toward this point of view.SourcesCampanelli, Pauline. The Wheel of the Year: Living the Magical Life. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1989.Moonstone, Carrie. “How to Make a Besom.” At Witchvox.Ristic, Radomir. Balkan Traditional Witchcraft. Michael C. Carter, Jr., trans. Los Angeles: Pendraig, 2009.Whitehurst, Tess. Magical housekeeping: Simple Charms and Practical Tips for Creating A Harmonious Home. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 2010.Zimmerman, Christine. A Pray or Ritual for a Broom Cleansing.In honor of the last article in the witch broom series, apropos of nothing, I leave you with my favorite magic broom video.

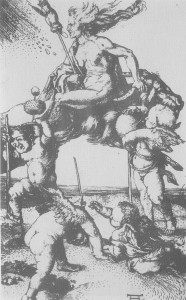

The first thing that we have to grapple with when we talk about the broom as a magical tool is that the sacred broom is not really a broom, not in the way it is commonly understood as a utensil for sweeping debris off the floor. So what is it? Is it the act of sweeping that makes the broom magical? Is it a cleaning application in the realm of etheric energies? Is it some quality in the materials sewn into the part that sweeps? Is it some quality in the handle? Does it relate to the broom’s relationship to the house? As we will see, all of these things play into the magical power of the broom.When we talk about witches riding their brooms, the cliched expression is “riding on their broomsticks.” Yet we don’t ordinarily refer to the handle of the broom in other contexts. For example, if I wanted someone to pass a broom to me, I would say, “hand me the broom,” not “hand me the broomstick.” Magically speaking, the stick in broomstick warrants examination.

The first thing that we have to grapple with when we talk about the broom as a magical tool is that the sacred broom is not really a broom, not in the way it is commonly understood as a utensil for sweeping debris off the floor. So what is it? Is it the act of sweeping that makes the broom magical? Is it a cleaning application in the realm of etheric energies? Is it some quality in the materials sewn into the part that sweeps? Is it some quality in the handle? Does it relate to the broom’s relationship to the house? As we will see, all of these things play into the magical power of the broom.When we talk about witches riding their brooms, the cliched expression is “riding on their broomsticks.” Yet we don’t ordinarily refer to the handle of the broom in other contexts. For example, if I wanted someone to pass a broom to me, I would say, “hand me the broom,” not “hand me the broomstick.” Magically speaking, the stick in broomstick warrants examination.