The autumn equinox coincides with the start of the major ceremonies of the Eleusinian mysteries. These ceremonies, which in Greco-Roman times attracted a huge number of attendees from all over the Mediterranean, guide participants into a deeper understanding of Persephone’s descent into the underworld. There are several versions of the myth of Persephone, which is too long to explain in detail here. The gist of it is that Persephone as a maiden goddess or “Kore” is painting flowers in a meadow when the earth opens up and the death god Hades abducts her. He demands that she stay in the underworld with him as his wife and queen and refuses to let her leave. Persephone’s mother Demeter is inconsolable and neglects her duties as mother of vegetation, leaving crops to wither from lack of rain. As the earth becomes more and more parched, the gods become alarmed, and finally the chief god Zeus orders Hades to relinquish his captive. Unfortunately Persephone has eaten a pomegranate seed while in the underworld, and the laws there decree that no one who takes food in the land of the dead may return to the living. Given the urgency of the situation, a compromise is nevertheless reached: Persephone will spend four months of every year in the underworld with Hades and will spend the rest of her time on earth with her mother Demeter. From Apollodorus:

The autumn equinox coincides with the start of the major ceremonies of the Eleusinian mysteries. These ceremonies, which in Greco-Roman times attracted a huge number of attendees from all over the Mediterranean, guide participants into a deeper understanding of Persephone’s descent into the underworld. There are several versions of the myth of Persephone, which is too long to explain in detail here. The gist of it is that Persephone as a maiden goddess or “Kore” is painting flowers in a meadow when the earth opens up and the death god Hades abducts her. He demands that she stay in the underworld with him as his wife and queen and refuses to let her leave. Persephone’s mother Demeter is inconsolable and neglects her duties as mother of vegetation, leaving crops to wither from lack of rain. As the earth becomes more and more parched, the gods become alarmed, and finally the chief god Zeus orders Hades to relinquish his captive. Unfortunately Persephone has eaten a pomegranate seed while in the underworld, and the laws there decree that no one who takes food in the land of the dead may return to the living. Given the urgency of the situation, a compromise is nevertheless reached: Persephone will spend four months of every year in the underworld with Hades and will spend the rest of her time on earth with her mother Demeter. From Apollodorus:

When Zeus commanded Pluto [Hades] to send Core [Kore] back up, Pluto gave her a pomegranate seed to eat, as assurance that she would not remain long with her mother. With no foreknowledge of the outcome of her act, she consumed it… Persephone was obliged to spend a third of each year with Pluto, and the remainder of the year among the gods.

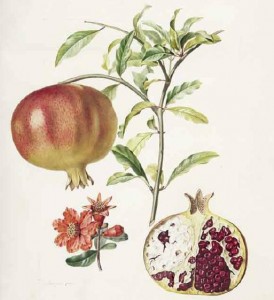

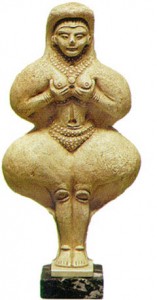

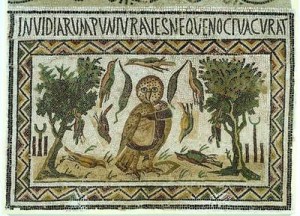

Persephone’s return to the upper world in February coincides with the lesser ceremonies of Eleusis.In addition to explaining the fallow period of the agricultural year, Persephone’s myth is believed to be an account of the merger of the Hellenic (Indo-European) pantheon with a much older one. The rape motif in the story underscores that the Hellenic takeover was a violent one that wrested power from women. In the words of Robert Graves, “It refers to male usurpation of the female agricultural mysteries in primitive times.”The pre-patriarchal Persephone was probably a triple goddess, with the maiden Kore her manifestation in early spring, the mother Demeter her mature aspect, and the queen of the underworld her death aspect. Note that Mediterranean goddesses were rarely depicted as hags or crones, even in their death aspect.Persephone’s symbols are many, but we are confining our attention here to the pomegranate. This tree, which is native to Afghanistan and surrounding regions, has been cultivated for at least 5000 years. It is probable that the fruit was traded even earlier, since pomegranates keep well and their flavor is enhanced during storage. Pomegranate trees grow easily from seed. They thrive in hot, semi-arid conditions, even in poor soil. After the pomegranate flowers, the burgeoning fruit has a pronounced crown. The fleshy red seeds are sectioned by membranes that are cavernous in appearance. The cave is a symbol of both the underworld and the womb. Red is the color of blood, the womb, and birth. Many ancient people in the Mediterranean and elsewhere painted dead bodies with the red mineral ocher to symbolize rebirth. Of course, seeds also symbolize birth, and the plethora of seeds inside the pomegranate make it an emblem of fertility.Provocative symbolism aside, the pomegranate is a useful fruit. The seeds have a pleasant, astringent taste that is not overly sweet. The seeds have long been used to treat tapeworms, and the rind can sooth irritated skin. The rind is also used to dye cloth yellow. The sacred trees of major goddesses usually have a long history of generosity to humans.