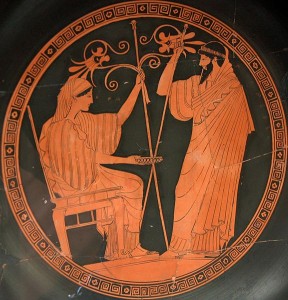

The Greek pantheon became large and complex because so many cultural influences shaped Greek history. New gods became incorporated through outside invasions, trade interactions, and the conquest of other states. The foundational strain of Greek civilization, called the Pelasgian culture by ancient Greek historians and part of the wider civilization of Old Europe by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, placed goddesses at the center of worship. Indo-European invasions introduced a patriarchal religion headed by a sky god Zeus. In time other deities were introduced through trade (e.g., Aphrodite) or conquest (e.g., Hecate). Meanwhile devotion to pre-Indo-European goddesses such as Artemis or Athena persisted.Like nearly all polytheistic societies, the Greeks absorbed new deities by incorporating them in a common religious framework. A favored way of doing this was to marry one of the old goddesses to a new god. The goddess Hera became the wife of god Zeus and Persephone the wife of Hades. Since marriage was seen as subjugation of the goddess, where the cult of a goddess was particularly strong she remained virgin, as in the case of Artemis or Athena. Another way of creating order in the pantheon was to assign specific functions to different deities. Thus Aphrodite was not allowed to do any “work,” but must (officially) stick to her realm of romantic love. Sometimes a deity with a weaker following would become the priestess of a deity with a more robust cult, especially if these deities had similar functions. Thus the Arcadian bear goddess Callisto was said to be a priestess of Artemis. The ecstatic Dionysus was followed by the wild goddesses known as the Maenads. Other times deities with similar functions would be subsumed under the name of the deity with the more powerful cult.

O Royal Juno [Hera] of majestic mien, aerial-form’d, divine, Jove’s [Zeus’] blessed queen,

Thron’d in the bosom of cærulean air, the race of mortals is thy constant care.

The cooling gales thy pow’r alone inspires, which nourish life, which ev’ry life desires.

Mother of clouds and winds, from thee alone producing all things, mortal life is known:

All natures share thy temp’rament divine, and universal sway alone is thine.

With founding blasts of wind, the swelling sea and rolling rivers roar, when shook by thee.

Come, blessed Goddess, fam’d almighty queen, with aspect kind, rejoicing and serene.

Hera is not only the goddess of marriage and the wife of Zeus, she is the creator of everything, the sustainer of life, the protector of people, the force that drives the wind, the waves, and the torrid rivers. She is a big deal.The problems in how we conceptualized the Greco-Roman gods in our high school English class increase exponentially when we begin applying this methodology to other pantheons. Our understanding becomes not only grossly reductionist, but wrong.Let’s look again at the Germanic pantheon. The Germanic tribes, like the Greek, had a steadily growing collection of deities to sort out. Unlike the Greeks, who lived for millennia in the same place and found themselves conquered and reconquered, the Germans grew their pantheon by conquering others and absorbing the local gods, then repeating the process many times as they moved westward. It is common wisdom that the gods of the Vanir branch (including Freya and Freyr), are the Old European gods and the larger Aesir branch (which includes Frigga, Odin, Thor and many others) is the Indo-European one, but the Aesir includes plenty of Old European deities that were absorbed at an earlier time. I have heard Odin described as the old warrior and Thor the young warrior; Skadi the winter goddess and Idunn the spring goddess; Frejya the woman warrior and Frigga the hearth goddess. These depictions are totally accurate but completely wrong.Sometimes a discussion of Germanic mythology from a functional perspective describes the afterlife as the Hall of Valhalla presided over by the god Odin. Only warriors go there, so Odin is the god of the warrior death realm while the goddess Hel is queen of death for ignoble people. But further reading of the myths reveals that half the slain in battle (actually the preferred half) go to Frejya’s Hall of Sessrymnir. Hel’s death field is a sheet of ice, but there is a death goddess by the name of Mengloth who lives on a hill in the underworld called Lyfjaberg. Frigga greets the dead from her island of Fensalir. The god Heimdall meets his faithful in his hall of Himinbjorg. The Germanic tribes seem to have sorted out their gods not by dividing functions, but by allocating real estate in the afterworld. They were a people who lived very close to death, after all.Unlearning high school mythology allows us to make better sense of the Germanic mythology penned by the first generations of Christians, and perhaps even to discern some of their conceptual errors. Next week we will again look at the goddesses Frejya and Frigga, and hopefully understand them in a better way.