Germane to my post last week on Frigga, here is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Divining with Animal Guides.

The origin of Germanic writing is complex. Late Bronze Age carvings and cave markings from Northern Italy to Sweden show some rune-like symbols, their meaning undeciphered. Readable runic script dates to the second century and was presumably derived from the Etruscan alphabet, with which it shares some symbols. The god Odin is credited with discovering the runes, eighteen of them to start, when he hung upside down from the world tree, Yggdrasil, for nine days and nine nights. It is essential to understand that runes are not and were not simply signs that could be manipulated to form language, although they certainly were used for that purpose. Runes have always been magical powers in and of themselves. They disclose hidden truths, they protect buildings, they form spells. They are the force behind what words they speak.

Since Odin found the runes while tied to the tree but did not invent them, we have to look deeper for their source. The deities who nourish Yggdrasil are the Norns Urd, Verthandi, and Skuld. They are the Norns we are usually talking about when we say “The Norns.” The Norns water Yggdrasil’s roots from a pool of water at the base of the tree. They are responsible for giving each person their destiny and can reveal the past, present, and future. They are usually the powers invoked when using runes for divination and they are the powers petitioned for changing life circumstances. In addition to tending the tree, the Norns tend a pair of swans who are said to be the parents of all swans in the world. The Norns themselves wear cloaks of swan feathers.

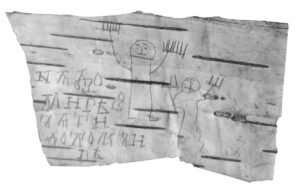

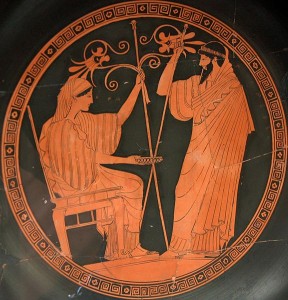

Another Germanic divinatory goddess is Frigga, who knows the future but seldom speaks of it. According to some sources it is she who bestows destiny on every child. Frigga’s distaff is in heaven and the stars revolve around it, which means she controls the calendar. Frigga wears a crown of heron feathers. Her sacred tree is the birch, probably the White Birch or Silver Birch. The white, supple bark of the birch has been used throughout northern Europe as a medium for writing and drawing. Natives in North America used the Paper Birch for similar purposes. Since bark is a degradable material it would be impossible to know how far back symbolic drawing on birch goes; extant pieces from Russia date to the twelfth century. Not much was recorded in Christian times about Frigga, despite her status as nominal head of the pantheon along with Odin, because clerics worked especially hard to erase all traces of her. Those who in later centuries recorded the Norse legends were men who would not have been privy to feminine traditions anyway. While Frigga is not explicitly documented as a writing goddess, information about her points in that direction.