The Norsemen: Myths and Legends, by H.A. Guerber.

The Norsemen: Myths and Legends, by H.A. Guerber.

First published 1908. (This review is from the 1994 Senate edition.)

I recently finished a cover-to-cover read of this book, which I have perused often over the past ten years. It’s a summary of information (in English) contained in medieval texts on Germanic mythology, as well as some of the work of the Grimm brothers. First published in 1908, it has a lot to offer in terms of comprehensiveness, organization, and readability.

First the comprehensiveness. Norse mythology is all the rage now, but twenty-first century authors, in an attempt to focus the massive unwieldy material, weed out the minor extemporaneous aspects. As in, almost all the goddesses and women. They also highlight the more interesting and exciting aspects of the mythology. As in, the violence.

Don’t get me wrong: Norse mythology is patriarchal and violent. It was recorded by early Scandinavian Christian men seeking to glorify their Pagan heritage in ways acceptable to the Church. But apparently twenty-first century audiences need more violence and more male dominance, though the part about sexy Freya sleeping with all those dwarves manages to slip in. Hence there is a need for serious students, seekers, and practitioners to move beyond selective texts, which almost always highlight and enhance a male focus.

Archeology suggests Norse culture, though violent and patriarchal, was less violent and patriarchal than portrayed in early literature. Most Norsemen were fishermen or farmers, not full-time warriors, and women were the custodians of the religion. Shamanic power was expressed more through magic spinning than through magic spears. If selectivity is to be used at all in presenting the Norse legends, it seems that it should bring the women’s sphere into sharper focus.

Next the organization. The chapters are well conceived, and they are divided into many sections that have titles across the top of the page. The index is quite detailed. I imagine most people use this book as a reference rather than reading from page one.

As for readability, here is an excerpt:

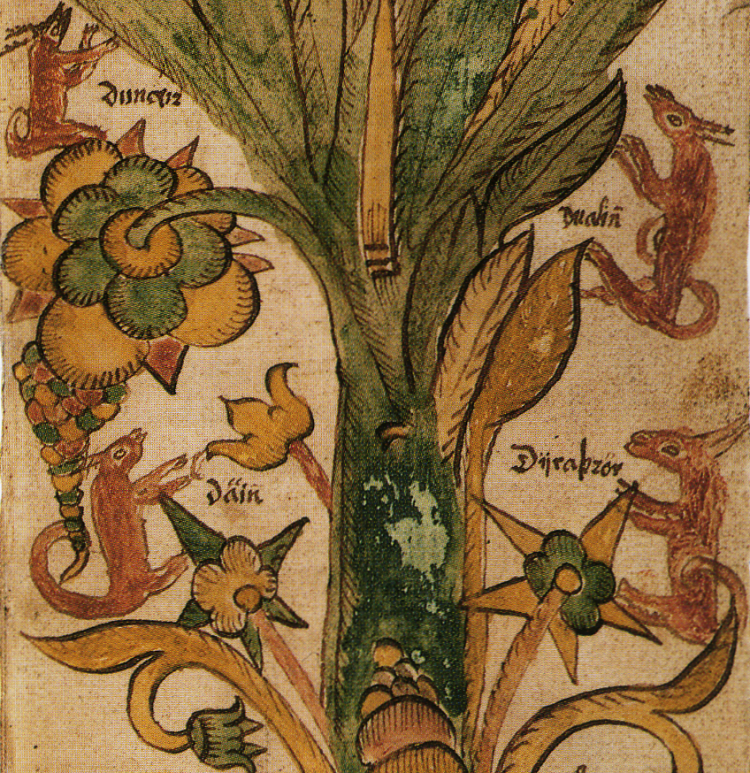

These three sisters, whose names were Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld, were personifications of the past, present, and future*. Their principle occupations were to weave the web of fate; to sprinkle daily the sacred tree with water from the Urdar fountain, and to put fresh clay around its roots, that it might remain fresh and ever green.

Some authorities further state that the Norns kept watch over the golden apples which hung on the branches of the tree of life, experience and knowledge, allowing none but Idun to pick the fruit, which was that with which the gods renewed their youth.

The Norns also fed and tenderly cared for two swans which swam over the mirror-like surface of the Urdar fountain, and from this pair of birds all swans on earth are supposed to be descended. At times, it is said, the Norns clothed themselves with swam plumage to visit the earth, or sported like mermaids along the coast and in various lakes and rivers, appearing to mortals, from time to time, to foretell the future or give them sage advice.

*Some consider this characterization overly simplistic.

(The chapter on the Norns runs for six pages.)

Problems? Sometimes I disagree with Guerber’s interpretation of a myth or deity, and occasionally so does feminist scholarship. She conflates deities and myths among European cultures in a way that was fashionable a century ago but is frowned on now. The text is not footnoted, and reviewers on Goodreads and Amazon complaining of errors seem to be unaware that there are multiple, sometimes conflicting, sources for the material presented. Sometimes she is simply wrong, but not often, and the same could be said for any work of this scope. A hundred years later, The Norsemen still holds up well.