Biblical sacrifice, the idea of which we have become more or less accustomed to, is basically a negative gesture: it deprives us – and we willingly accept this deprivation – of something we reserve for God without his having a need or use for it. In Mesopotamia, on the other hand, sacrifice, offerings to the gods, were positive actions: what was given to them, they needed.

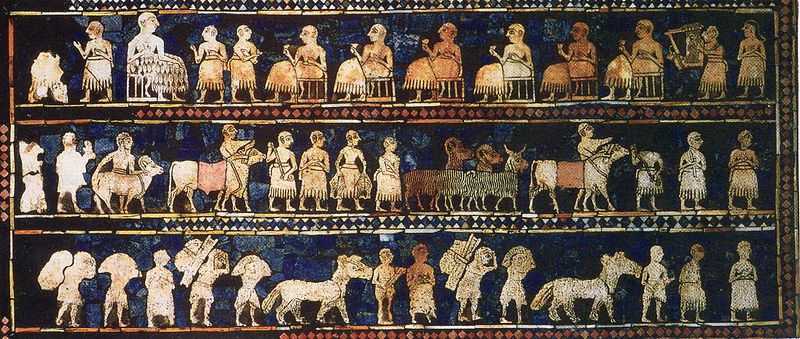

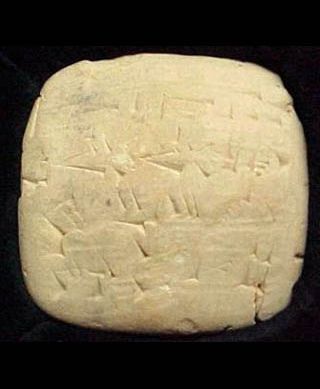

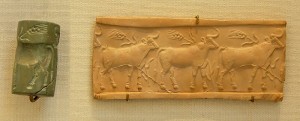

In order to understand the role of food in religious life, it is also necessary to move out of contemporary constructs about food. We think of food as fuel or sustenance, we think of food as sensory enjoyment, we think of certain foods as symbolic, and we think of shared food as a means of social cohesion. For Mesopotamians food was all of these things, but it was something more. Food was imbued with certain powers, particularly the power of life. The various prayers and ceremonies involved in the harvesting, milling, butchering, and preparing of food enhanced these powers and added new ones. Recall that when Inanna is trapped in the underworld unable to save herself, the god Enki sends his representatives down to revive her with the “bread of life” and “water of life.” Recall also from the previous post that Ereshkigal participated in an important ceremony not by being present but by partaking in the food that was served. Throughout Sumerian and Akkadian myth the idea is implied but not specifically spelled out that food is a means of disseminating power.Millers, farmers, herders, and others donated the basic ingredients to meet the voracious appetites of the gods. There were specifications about how animals destined for the temple should be raised and fed. All of the meat was high quality and some of it was exceptional. Special prayers were spoken when butchering temple animals or when milling grain that would be used for temple bread. Though high quality ingredients were used in food preparation, and meals were served on the finest platters and vessels by priests or priestesses dressed in immaculate clothing, the recipes themselves were basic. Meat was grilled or boiled rather than simmered in the elaborate sauces that characterized Mesopotamian cooking from the empire stage onward, at least for people with means. The gods were believed to be traditionalists in their culinary tastes, preferring food as it was prepared in prehistory.What finally became of all that food? The accounting involved in meeting the meal specifications for the gods must have been daunting in itself. In fact, we have learned much about the feeding of the gods by making inferences from temple accounting records, which are extensive. The food could not have been left outside the city once the gods had gorged themselves without creating a huge problem with lions, hyenas, and other scavengers. Nor could this much food have been consumed by the what must have been a large temple staff. Though Mesopotamian cultures in historic times, and even in the archaeological records of prehistory, were highly class stratified, this food would not have been destined for the tables of aristocrats. As mentioned a few posts back, rich men employed an extensive kitchen staff to prepare elaborate meals catering to their sophisticated tastes. They would not have eaten such simple food except when participating in religious rites. Unfortunately the temple accountants did not see a need to document how the food was disbursed once the gods had eaten their share. Probably it was given away.SourceBottero, Jean. The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

In order to understand the role of food in religious life, it is also necessary to move out of contemporary constructs about food. We think of food as fuel or sustenance, we think of food as sensory enjoyment, we think of certain foods as symbolic, and we think of shared food as a means of social cohesion. For Mesopotamians food was all of these things, but it was something more. Food was imbued with certain powers, particularly the power of life. The various prayers and ceremonies involved in the harvesting, milling, butchering, and preparing of food enhanced these powers and added new ones. Recall that when Inanna is trapped in the underworld unable to save herself, the god Enki sends his representatives down to revive her with the “bread of life” and “water of life.” Recall also from the previous post that Ereshkigal participated in an important ceremony not by being present but by partaking in the food that was served. Throughout Sumerian and Akkadian myth the idea is implied but not specifically spelled out that food is a means of disseminating power.Millers, farmers, herders, and others donated the basic ingredients to meet the voracious appetites of the gods. There were specifications about how animals destined for the temple should be raised and fed. All of the meat was high quality and some of it was exceptional. Special prayers were spoken when butchering temple animals or when milling grain that would be used for temple bread. Though high quality ingredients were used in food preparation, and meals were served on the finest platters and vessels by priests or priestesses dressed in immaculate clothing, the recipes themselves were basic. Meat was grilled or boiled rather than simmered in the elaborate sauces that characterized Mesopotamian cooking from the empire stage onward, at least for people with means. The gods were believed to be traditionalists in their culinary tastes, preferring food as it was prepared in prehistory.What finally became of all that food? The accounting involved in meeting the meal specifications for the gods must have been daunting in itself. In fact, we have learned much about the feeding of the gods by making inferences from temple accounting records, which are extensive. The food could not have been left outside the city once the gods had gorged themselves without creating a huge problem with lions, hyenas, and other scavengers. Nor could this much food have been consumed by the what must have been a large temple staff. Though Mesopotamian cultures in historic times, and even in the archaeological records of prehistory, were highly class stratified, this food would not have been destined for the tables of aristocrats. As mentioned a few posts back, rich men employed an extensive kitchen staff to prepare elaborate meals catering to their sophisticated tastes. They would not have eaten such simple food except when participating in religious rites. Unfortunately the temple accountants did not see a need to document how the food was disbursed once the gods had eaten their share. Probably it was given away.SourceBottero, Jean. The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.