All Hail the Winsome Freya

All Hail the Mighty Cerridwyn

All Hail the Nourishing Demeter

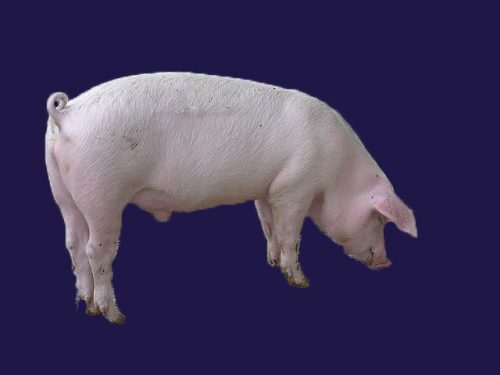

These triple goddesses have traditionally been worshiped in porcine form. The pig embodies the generating, nourishing, destroying aspects of the Triple Goddess.

All Hail the Winsome Freya

All Hail the Mighty Cerridwyn

All Hail the Nourishing Demeter

These triple goddesses have traditionally been worshiped in porcine form. The pig embodies the generating, nourishing, destroying aspects of the Triple Goddess.

There is a curious section in Aradia: Gospel of the Witches by Charles Leland that describes the goddess Diana’s incarnation in human form and her marvelous spellcasting to impress the witches. The passage says that “she declared that she would darken the heavens and turn all the stars into mice.” Diana duly accomplishes this feat, the heavens rain with mice, and Diana is crowned Queen of the Witches.

So why does Diana make it rain mice, of all things, to impress the witches? The answer lies in the dual roles of Apollo, as god of light and god of mice. Possibly these roles became syncretized with Apollo as he absorbed many other gods, but at any rate Diana was turning the stars (light) into another of their forms: mice. This is why Diana once chose to make it rain mice.

Ever wonder about the phrase “It’s raining cats and dogs”? Most people recognize this as a description of a fierce rain shower, but have you ever seen cats and dogs pouring down from the sky?

The folklore behind the saying has two parts. A lightning strike in European folklore (and in some other places, such as the Philippines) is associated with a dog bite. That makes sense: electricity has a bite to it, so being struck by lightning probably would feel like a dog bite.

What about the cats? There is also a longstanding belief in folklore that cats cause it to rain by vigorously washing their faces.

So, raining cats and dogs refers to a type of storm where there is torrential rain (caused by the cats) and lightning (biting dogs).

The big excitement this week has been the appearance of a Great Gray Owl, a boreal owl rarely seen in the United States. As the name implies, this is a very large owl, bigger even than the Great Horned. The wingspan is huge, but a blur in my camera even flying slowly.

No one knows if this is a female or male, though one birder thought this owl is female based on the size (female owls tend to be slightly larger, but the difference is not great enough for identification). The owl was unconcerned about the group of people nearby and concentrated on hunting rodents. As word has spread, people have been flocking here from out-of-state.

What does it all mean? On one level, that food for this bird in the far north has been scarce this winter. Possibly we have had a greater mouse or vole irruption, though I haven’t noticed it. Gray Owls have also been spotted in the past few weeks in Maine and New Hampshire.

This was not a personal sign since I was told where the bird was feeding in the late afternoon and went looking for it, but it is a sign for the nearby community as whole, which has talked of little else this week. I ordinarily don’t place credence on superstitions about seeing owls in daylight and don’t know anyone who does, partly because we see so many owls during the day around here.

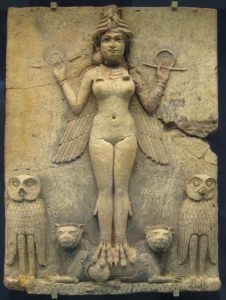

The owl is the sacred bird of Ishtar, probably because the owl protects the grain by hunting rodents. The owl was also a women’s symbol in Mesopotamia. Women wore owl amulets during childbirth and the prostitutes’ union used the owl as their totem. I interpret this owl as an intervention from outside to rid the community of the vermin of noxious ideas.

In the next day or two as weather becomes warmer, the owl is expected to move north.

Then said Gangleri: “Which are the Asynjur?” Harr said: “Frigg is the foremost: she has that estate which is called Fensalir, and it is most glorious.”

— The Prose Edda, Snorri Sturluson, translated Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur.

Deities tend to become conflated over time, particularly female deities. When a major goddess enters the historical record in an obscure manner, the situation becomes more pronounced. Such is the case with Frigga, possibly at one time the most widely worshipped of the Germanic gods. Often confused with the beautiful and loving Frejya, Frigga is very much a goddess of her own realm.

The term “Asynjur” mentioned above means “goddess” in this case, though it can refer specifically to the branch of Germanic deities known as the Aesir. Marija Gimbutas classifies the two branches as a conjoining of Old European and invading Indo-European pantheons: “The Vanir represent the indigenous, Old European deities, fertile and life giving. In contrast, the Aesir embody the Indo-European warrior deities of a patriarchal people.”(1) I view this assessment, and Frigga’s place in it, not as false but as overly facile. The Vanir was undoubtedly drawn into the Aesir, with the Aesir All-Father Odin the dominant deity of the new pantheon, but the more populated Aesir had probably absorbed other pantheons at an earlier time. I believe Frigga was a central goddess of a matriarchal culture who was absorbed into Odin’s cult by “marriage,” a time-honored way of combining pantheons. Frigga’s marriage to the head of the patriarchal pantheon signals her importance. Her cult seems never to have been entirely subdued, because she retains her own sphere and is more than a match for Odin. In two stories she outwits the All-Father.

While Germanic deities have their own personalities, their individuation is expressed less with symbols and functions, which often overlap, than with territory. Frigga’s place is the slow-moving, marshy river and her glorious estate of Fensalir is an island within the freshwater marshland. The Grey Heron dominates this type of landscape, and Frigga is said to wear a crown of heron feathers. She has also been mentioned as owning hawks, which might be a conflation with Frejya, but could allude to another bird of this landscape, the osprey. I think of her as the great fish eater. She harvests souls swimming in the water of life and so rules over fate.

Frigga’s tree is the European White Birch, which grows well in wet soil along rivers. No doubt her house — or nest — is birch. (For more on this association see my post Frigga and the Birch.) She is the goddess of spinning, with the stars her distaff, which makes her the goddess of the year. Frigga’s status as sun goddess is revealed by her function as goddess of time and her association with gold. If twelve other goddesses mentioned in the Prose Edda are Frigga’s handmaidens, as Diana Paxson maintains(2), this further support the conjecture that she is a sun goddess.

As mother goddess Frigga rules that other fishy place, a woman’s vulva. The sexual connotations of the word “frigg” are derived from her name. (For those who don’t know what frigging is, I explain it here in this video.) Christianity has successfully divided the mother from the sexual being in our minds, thus encouraging the distinction of Frigga as mother goddess as opposed to Frejya as love goddess, yet earlier Pagans knew no such separation.

Frigga is described in the literature as the goddess who knows the future but seldom speaks of it. Herons also walk silently in the still waters, typically quiet except in the rookery. Frigga gives the child her destiny at birth. Her mastery of divination can be traced to her death-goddess huntress aspect or to her spindle which commands time. Birch bark as writing medium ties Frigga to the runes and their association with divination and spells.

While Frejya and Odin divide the heroic who die in battle between them, those good souls who lead a humbler life go to Fensalir after death. This gentle, loving goddess did not rise to prominence in a warrior culture.

I associate Frigga with the smell of fishy water, which I love, and quiet ponds teeming with dragonflies, frogs, and vegetation. She is the stately heron stalking the water’s edge. She is also the beautiful composed matron, the mistress of a rich but comfortable house. She is wise beyond measure, and though we hang on her words she listens more than she speaks.

The fate of all does Frigg know well,

Though herself she says it not

— The Poetic Edda, translated by Henry Addams Bellows

Notes

1. Marija Gimbutas, The Living Goddesses (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999), p. 191.

2. Diana L. Paxson, “Beloved: On Frigg and Her Handmaidens,” at Hrafnar: Twenty Years of Re-Inventing Heathenry

It’s been a frustrating week in foreign language study. For some reason, Samhain has been on patrol a bit more than usual, enforcing the household English-only policy.

This policy was instituted by the cat. She yowls whenever I review my Munsee vocabulary. A Siamese can yell louder than any person, so this is a ban she can enforce. She has an Irish name and her ancestors immigrated from Thailand, but she won’t tolerate any spoken word other than English. Today I thought she was taking a nap, so I opened my language materials, and then she walked in and I thought “Oh no.” Then I said (in English) “This is ridiculous.”

The cat I had before used to start crying when Spanish was spoken in the house, and since we were living in Tucson at the time it couldn’t always be avoided. Don’t tell me animals can’t understand what we’re saying, because they go berserk when they think we’re talking in code. When I was a teenager we had a poodle who was unusually smart, and we actually had to start spelling certain words instead of saying them, because if he got wind that we were up to something he wanted included in, he would begin campaigning strongly to go along. Eventually he became suspicious whenever we started spelling. Nobody likes being left out.

Munsee is actually not a foreign language but one of the Native Algonquian languages, so Samhain is not only a fascist but a colonialist. Starting today, I am going to push back against this reign of tyranny I find myself living under.

So again I am musing, as I do every winter, about the plethora of Snowshoe Hare tracks with no Hares in sight. Yet during this outing I did spy a Great Horned Owl gliding between the branches. Snowshoe Hares are hard to spot, but I suspect this owl is up to the challenge. In most photos it’s taken me about a minute to spot the Hare even though the frame is small and I know it’s there. I’ll bet these bunnies are all around me and I just don’t see them.

I’m more and more aware that it’s not just the trees, rocks, and water that witness my presence in the woods. All around me are eyes peering behind twigs and bushes. I’m never alone.

No reviews either. I’m getting ready to submit the manuscript for my next book so I’m a bit distracted from blogs and blogging. I’ll let my cat Samhain handle the post this week. This picture was taken right after she threw my pen on the floor. Part of an international cat conspiracy to infiltrate the homes of writers and decrease the output of literature. Cats do not like books.

I’ve written a lot about deer, especially reindeer, this year. Here is a poem about the Saami reindeer sun goddess Beiwe.

She rides across heaven in antler wagon.

She rides across heaven in antler wagon.

Holding her daughter, she defines the day.

Holding her daughter, she defines the day.

She crosses antler heaven holding her daughter,

defining a day in the wagon ride.

Bring peace to hearts in the blackness.

Bring peace to hearts in the blackness.

Offer red blood of white reindeer.

Offer red blood of white reindeer.

In the heart of the blackness offer red blood.

White reindeer bring peace.

Bring light to wake forest in springtime.

Bring light to wake forest in springtime.

Make rings of birch branches.

Make rings of birch branches.

Birch forest light rings, bring branches, make

time wake the spring.

Her reindeer daughter brings heart. Her reindeer

antlers hold the light of day. In the

forest she wakes blood in birch. Time

branches, crosses heaven, makes

an offering. Black, red, white define

the wagon ride. Peace.