The horror of today’s shooting at the elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut is too extreme to be expressed in words, so I will not try. I know that we all are profoundly affected. Children, and not only the children at the school, will be traumatized by the event. News media will be obsessed with these events for several weeks, perhaps justifiably so, and the exposure of children to the constant and macabre details that emerge will need to be monitored.As the president noted in his briefing, mass shootings by the solitary gunman are happening at an intolerable frequency, and I pray that his promise that concrete action to prevent further atrocities will be fulfilled. The forthcoming discussion will probably include a look at ways of banning assault weapons and restricting gun ownership by mentally unstable individuals, as well as drawing attention to the limited availability of competent mental health treatment. I wonder if and when we will ever look at the fact that these shootings are nearly always committed by males. Certainly not all men are violent, but the role of male socialization in creating violence will have to be addressed at some point if we are ever to live in a peaceful world.In rural America we tend to think of violence, particularly violence from strangers, particularly violence on a massive scale, as being an urban problem. We need to break through the tendency to isolate ourselves from the idea of violence occurring where we live in order to address the problem on a cohesive level.

Category: Uncategorized

Another post at Return to Mago

November 29, 2012

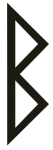

Brigid and the Mountain Ash

November 9, 2012

I was feeling rather smug about my identification of a new magical tree, when I learned that the American Mountain Ash is a New World subspecies of the rowan tree. Oh well.Every beginning magic student hears about the rowan tree. The tree with magic berries, protected by a dragon. The source of the best wands. The tree of strong protection, which banishes lightening. The tree of vision. Both saints and heroes had some of their most extraordinary revelations under the rowan tree. “What’s a rowan tree?” I recall asking on more than one occasion. The response would be, “Oh, it’s some tree that grows in England, and it [recites a litany of magical qualities].” Why didn’t anyone tell me that the rowan is the Mountain Ash? Because they didn’t know. Because most of us learn about witchcraft in urban settings. Because I was studying in California, and the Mountain Ash doesn’t grow there any more than the rowan does. Because the study of magic has gotten lost in its abstractions. This is one of the reasons I started the Yellow Birch School of Magic, because I wanted to connect pagans with the tangible foundations of magical practice.The rowan is the tree for the second month of the Celtic tree calendar. Says Robert Graves, “The important Celtic feast of Candlemas fell in the middle of it (February 2). It was held to mark the quickening of the year…” Quickening refers to the point in the pregnancy where fetal movements can be felt by the mother. In folklore it is believed to be the time when the spirit incarnates in the growing fetus. Graves goes on to say “Since it was the tree of quickening, it could also be used in a contrary sense. In Danaan Ireland a rowan-stake hammered through a corpse immobilized its ghost; and in the Cuchulain saga three hags spitted a dog, Cuchulain’s sacred animal, on rowan twigs to procure his death.”By identifying the rowan tree with Candlemass, I have given away the link between this tree and the Celtic goddess Brigid. February 2nd is also known as “Brigid’s Day.” Brigid is the Celtic fire goddess. Patricia Monaghan says of her pre-Christian worship, “She may have been seen as a bringer of civilization, rather like other Indo-European hearth goddesses (Vesta, Hestia) who ruled the social contract from their position in the heart and hearth of each home.” Fire is associated with vision, and Brigid’s Day is a day for divination, particularly weather divination. This is why the groundhog sees or doesn’t see his shadow on this day. And how is the rowan tree connected with fire? For that we have to go back to those little orange berries, the color of a warm fire.SourcesGraves, Robert. The White Goddess. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.Ketchledge, E.H. Forests and Tress of the Adirondack High Peaks Region. Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club, 1967.Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.Ristic, Radomir. Balkan Traditional Witchcraft. Trans. Michael C. Carter, Jr. Sunland, CA: Pendraig, 2009.Tree Encyclopedia. American Mountain Ash – Sorbus americana

I was feeling rather smug about my identification of a new magical tree, when I learned that the American Mountain Ash is a New World subspecies of the rowan tree. Oh well.Every beginning magic student hears about the rowan tree. The tree with magic berries, protected by a dragon. The source of the best wands. The tree of strong protection, which banishes lightening. The tree of vision. Both saints and heroes had some of their most extraordinary revelations under the rowan tree. “What’s a rowan tree?” I recall asking on more than one occasion. The response would be, “Oh, it’s some tree that grows in England, and it [recites a litany of magical qualities].” Why didn’t anyone tell me that the rowan is the Mountain Ash? Because they didn’t know. Because most of us learn about witchcraft in urban settings. Because I was studying in California, and the Mountain Ash doesn’t grow there any more than the rowan does. Because the study of magic has gotten lost in its abstractions. This is one of the reasons I started the Yellow Birch School of Magic, because I wanted to connect pagans with the tangible foundations of magical practice.The rowan is the tree for the second month of the Celtic tree calendar. Says Robert Graves, “The important Celtic feast of Candlemas fell in the middle of it (February 2). It was held to mark the quickening of the year…” Quickening refers to the point in the pregnancy where fetal movements can be felt by the mother. In folklore it is believed to be the time when the spirit incarnates in the growing fetus. Graves goes on to say “Since it was the tree of quickening, it could also be used in a contrary sense. In Danaan Ireland a rowan-stake hammered through a corpse immobilized its ghost; and in the Cuchulain saga three hags spitted a dog, Cuchulain’s sacred animal, on rowan twigs to procure his death.”By identifying the rowan tree with Candlemass, I have given away the link between this tree and the Celtic goddess Brigid. February 2nd is also known as “Brigid’s Day.” Brigid is the Celtic fire goddess. Patricia Monaghan says of her pre-Christian worship, “She may have been seen as a bringer of civilization, rather like other Indo-European hearth goddesses (Vesta, Hestia) who ruled the social contract from their position in the heart and hearth of each home.” Fire is associated with vision, and Brigid’s Day is a day for divination, particularly weather divination. This is why the groundhog sees or doesn’t see his shadow on this day. And how is the rowan tree connected with fire? For that we have to go back to those little orange berries, the color of a warm fire.SourcesGraves, Robert. The White Goddess. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.Ketchledge, E.H. Forests and Tress of the Adirondack High Peaks Region. Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club, 1967.Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.Ristic, Radomir. Balkan Traditional Witchcraft. Trans. Michael C. Carter, Jr. Sunland, CA: Pendraig, 2009.Tree Encyclopedia. American Mountain Ash – Sorbus americana

A Wonderful Samhain to Everyone

October 31, 2012The Hard Side of Aphrodite

October 4, 2012

Frigga and the Birch

September 7, 2012

It’s all in how you see it

August 30, 2012 The internets have been in a titter for a week, and no doubt every Blue Moon café, restaurant and tavern is in high celebratory mode. Really, the significance of the Blue Moon is that it is hard to categorize. Solar and lunar time only reconcile about every nineteen years, so there are twelve lunar cycles and some change in any solar year. Whether there are twelve or thirteen full moons depends on which day you start the calendar. Depending on the tradition (and the latitude), we label each month’s moon according to its seasonal significance. Thus the January moon is the “Wolf Moon”, the February moon is the “Hungry Moon,” the March moon is the “Storm Moon,” etc. What happens when you have two full moons in a month? You don’t know how to categorize the second one. It’s also an uncommon occurrence, occurring only about every three years.A Blue Moon is a full moon in which you do something you wouldn’t ordinarily do, and something that you probably won’t do again for awhile. When I had a large teaching coven, the women would circle with the men on that night, just to show that we were not categorically opposed to it (but still not willing to make it a regular occurrence).The color blue in lunar context has some significance. Red is ordinarily the color associated with the full moon (look at it closely some time), a phenomenon that was easier to see when the moon was closer to the earth. Red is a very powerful magical color, associated with the Mother and characteristic of the Dianic Tradition. White is the color of the waxing moon, associated with the Maiden, while black is the color of the Crone and the dark portion of the waning moon. Thus we have the three important magical colors of the Dianic Tradition and many others. Blue is a cooling color less frequently invoked, which nonetheless has its own important properties. If colors are invoked when casting a circle, blue is often linked with the direction of West. In shamanic traditions which are based on the number four, unlike Indo-European cultures, which are almost always based on the number three, blue is usually included as one of the four basic colors.A lot of pagans are saying that the Blue Moon has very special powers, but I disagree with this. In and of itself, the Blue Moon only has meaning if you accept the validity of the Julian calendar. How many of us do? I accept that I have to work with this calendar, to navigate the business and larger social world, but magically my calendar is marked in different time, beginning on November 1st. Other people may start their year at the winter solstice, or the spring equinox, or at some other time. What gives the Blue Moon its significance is the the permission people give themselves to loosen up, be unorthodox, try something new. This is the special energy that drives the Blue Moon.

The internets have been in a titter for a week, and no doubt every Blue Moon café, restaurant and tavern is in high celebratory mode. Really, the significance of the Blue Moon is that it is hard to categorize. Solar and lunar time only reconcile about every nineteen years, so there are twelve lunar cycles and some change in any solar year. Whether there are twelve or thirteen full moons depends on which day you start the calendar. Depending on the tradition (and the latitude), we label each month’s moon according to its seasonal significance. Thus the January moon is the “Wolf Moon”, the February moon is the “Hungry Moon,” the March moon is the “Storm Moon,” etc. What happens when you have two full moons in a month? You don’t know how to categorize the second one. It’s also an uncommon occurrence, occurring only about every three years.A Blue Moon is a full moon in which you do something you wouldn’t ordinarily do, and something that you probably won’t do again for awhile. When I had a large teaching coven, the women would circle with the men on that night, just to show that we were not categorically opposed to it (but still not willing to make it a regular occurrence).The color blue in lunar context has some significance. Red is ordinarily the color associated with the full moon (look at it closely some time), a phenomenon that was easier to see when the moon was closer to the earth. Red is a very powerful magical color, associated with the Mother and characteristic of the Dianic Tradition. White is the color of the waxing moon, associated with the Maiden, while black is the color of the Crone and the dark portion of the waning moon. Thus we have the three important magical colors of the Dianic Tradition and many others. Blue is a cooling color less frequently invoked, which nonetheless has its own important properties. If colors are invoked when casting a circle, blue is often linked with the direction of West. In shamanic traditions which are based on the number four, unlike Indo-European cultures, which are almost always based on the number three, blue is usually included as one of the four basic colors.A lot of pagans are saying that the Blue Moon has very special powers, but I disagree with this. In and of itself, the Blue Moon only has meaning if you accept the validity of the Julian calendar. How many of us do? I accept that I have to work with this calendar, to navigate the business and larger social world, but magically my calendar is marked in different time, beginning on November 1st. Other people may start their year at the winter solstice, or the spring equinox, or at some other time. What gives the Blue Moon its significance is the the permission people give themselves to loosen up, be unorthodox, try something new. This is the special energy that drives the Blue Moon.

Another Post at the Mago Blog

August 23, 2012I have another guest post at “Return to Mago.” The article describes my meeting with the Sumerian death goddess Ereshkigal.

The Woman Who Walks With the Wolves

July 27, 2012The Linden Prophesy

July 20, 2012 The tree goddess this week is the Latvian Laima (pronounced like the first word in “lima bean”). Her Lithuanian name is Laime. Be careful not to get her confused with the fairy goddess Lauma or the Greek Lamia.Laima is associated with many trees, but especially the linden; many birds, but especially the cuckoo; and many animals, but especially the cow. Laima is the goddess of birth, fertility, fate and prosperity — goddess qualities that seem to go together. Laima measures the length of the day, the length of a lifespan, the length of a spell of good luck. I have a mental picture of her flying around with a wooden ruler measuring things. (“Baby girl, you are going to be this tall.”)

The tree goddess this week is the Latvian Laima (pronounced like the first word in “lima bean”). Her Lithuanian name is Laime. Be careful not to get her confused with the fairy goddess Lauma or the Greek Lamia.Laima is associated with many trees, but especially the linden; many birds, but especially the cuckoo; and many animals, but especially the cow. Laima is the goddess of birth, fertility, fate and prosperity — goddess qualities that seem to go together. Laima measures the length of the day, the length of a lifespan, the length of a spell of good luck. I have a mental picture of her flying around with a wooden ruler measuring things. (“Baby girl, you are going to be this tall.”)

A branchy linden tree grewIn my cattle stall.This was not a linden tree,This was Laima of my cows.

Laima produces goats and sheep from her other trees:

All roadsides were covered with Laima’s trees:From a birch a ewe was born,From an aspen-tree, a little goat.

It is common in Euro-shamanism for land animals to have a bird form. Here we have sheep and goats with tree forms.Of course Laima also measures the length of a woman’s pregnancy and presides at the birth of children. She governs the bathhouse and sauna where Latvian women traditionally gave birth. In this role she takes the form of a woman with braided hair bearing linden branches.

Why so swift Mother LaimaWith linden twigs in your hand?To still the tears of a young brideWho came last year to our land.

Laima can appear as one goddess, three goddesses, or as many as seven. In various aspects she may be given different titles, such as “Cow Laima” or “Fate Laima.” This is interesting in the context of the linden tree, because its trunk often looks like it has multiple trunks fused together. The American Basswood has several distinct trunks rising from a single base. The linden tree exemplifies the idea of the goddess who is many and one.