I have a post in this week’s Return to Mago eZine: This Disappearing Leadership, in response to what happened at Fayetteville Goddess Festival. It’s about a need to reflect on power and control tactics being used in the Pagan communities.

I have a post in this week’s Return to Mago eZine: This Disappearing Leadership, in response to what happened at Fayetteville Goddess Festival. It’s about a need to reflect on power and control tactics being used in the Pagan communities.

Troubled by bothersome mold and mildew? There’s a god for that! Robigus is the Roman deity of rust and mildew. His honorary day is April 25. Implicit in the worship of deities who rule over things we find abhorrent is the recognition that these things do have a place — just not in our house, please. Pray to Robigus to keep rust off your ritual tools and mildew from you ritual spaces.

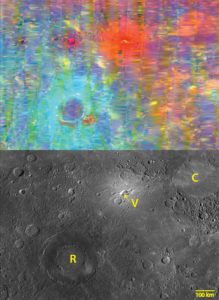

Both Mercury and Venus are retrograde right now, along with Jupiter and Saturn, but don’t freak out just yet.

“Retrograde” simply means that from our Earth perspective the planets are going “backwards” in the sky, although in reality they are tootling along like they always do. The outer planets are retrograde a good part of the time, so Jupiter and Saturn retrograde seems like business as usual, nothing to remark upon. Jupiter, for example, went retrograde in February and will go direct in June before going retrograde again in March of next year. Venus is more significant, as this planet goes retrograde every few years for about six weeks. Venus will go direct in a few days, so that retrograde is about done until June 2020.

So what about Mercury? That’s the retrograde people have learned to fear. I have written before on this blog how retrograde Mercury is a shift in attention, usually toward an area that has not been getting much focus. I recommend taking another look at this post.

My understanding of retrogrades, and particularly Mercury retrograde, is undergoing another transformation. I am especially taking exception to the admonition frequently given that the problems of Mercury retrograde are “your own damn fault. If you’d just been conscientious about your diet/maintenance/bookkeeping you wouldn’t have anything to fear from Mercury retrograde.” I don’t like this perspective because, for one thing, we can’t focus everywhere at once: our lives are too complex. The shift in attention may be needed, if unwelcome, but it’s not necessarily a punishment. You may have to take “lessons” from what happens at this time or you may not, depending on the situation. Whatever happens, you will find yourself preoccupied with things you don’t normally think too much about, though they will (probably) not be bizarre or highly unusual things.

But my thinking has evolved a bit further, to the point where I actually look forward to Mercury retrograde. Yes, it can be a wonderful time! This is when problems are addressed and often resolved, usually problems dealing with health, communication, finance, commerce, construction, or machinery. They can be hidden problems rising to the surface, which is the aspect of Mercury that is frustrating, or they can be longstanding problems. It’s a great time to proofread, revise, revisit, and reflect.

Take advantage of these next few weeks to problem-solve and resolve issues, especially the niggling kind that sap your energy. This may be the time you admit that you’re over your head in certain areas and go the doctor, hire a bookkeeper, or ask a friend to help you organize a project. This is a good time to use your magic for solving personal problems that seem outside your control.

Early the other day, while I was reading the nature poet Pattiann Rogers, my pancakes got a bit scorched in the griddle. I probably should not mention my name in the same post as Pattiann Rogers, lest comparisons be made, but the incident reminded me of this poem I wrote at this time last year.

Breakfast at My House

I am eating poems for breakfast.

Giraffes, dragonflies, and polar bears stalk

my kitchen. It is spring, it is winter, it is sunset, it is

too late – another burned pancake

goes in the trash.

I ponder food as a metaphor for wisdom while the cat

chows down on the scrambled tofu. The poignancy of life’s

impermanence hits home as the coffee

grows cold.

You can’t eat poetry, said my mother, but

I know you can, because I know what poetry

tastes like. It is soggy cereal and scorched potatoes.

It is charred polenta. It is over-steeped tea.

Millions of people

are eating poems for breakfast, and it is

the only meal that leaves you

really full.

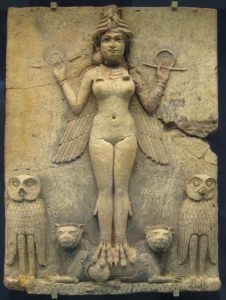

Ishtar amongst the gods, extraordinary is her station.Respected is her word, it is supreme.Strong, exalted and splendid are her decrees.The gods continually cause her commands to be executed:All of them bow down before her.

March 22nd marks the 27th anniversary of my ordination as priestess of Ishtar.

Hail to the Queen of Women, Mistress of Animals, Embodiment of Righteousness, the Beautiful Light of Heaven.

The big excitement this week has been the appearance of a Great Gray Owl, a boreal owl rarely seen in the United States. As the name implies, this is a very large owl, bigger even than the Great Horned. The wingspan is huge, but a blur in my camera even flying slowly.

No one knows if this is a female or male, though one birder thought this owl is female based on the size (female owls tend to be slightly larger, but the difference is not great enough for identification). The owl was unconcerned about the group of people nearby and concentrated on hunting rodents. As word has spread, people have been flocking here from out-of-state.

What does it all mean? On one level, that food for this bird in the far north has been scarce this winter. Possibly we have had a greater mouse or vole irruption, though I haven’t noticed it. Gray Owls have also been spotted in the past few weeks in Maine and New Hampshire.

This was not a personal sign since I was told where the bird was feeding in the late afternoon and went looking for it, but it is a sign for the nearby community as whole, which has talked of little else this week. I ordinarily don’t place credence on superstitions about seeing owls in daylight and don’t know anyone who does, partly because we see so many owls during the day around here.

The owl is the sacred bird of Ishtar, probably because the owl protects the grain by hunting rodents. The owl was also a women’s symbol in Mesopotamia. Women wore owl amulets during childbirth and the prostitutes’ union used the owl as their totem. I interpret this owl as an intervention from outside to rid the community of the vermin of noxious ideas.

In the next day or two as weather becomes warmer, the owl is expected to move north.

Germane to my post last week on Frigga, here is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, Divining with Animal Guides.

The origin of Germanic writing is complex. Late Bronze Age carvings and cave markings from Northern Italy to Sweden show some rune-like symbols, their meaning undeciphered. Readable runic script dates to the second century and was presumably derived from the Etruscan alphabet, with which it shares some symbols. The god Odin is credited with discovering the runes, eighteen of them to start, when he hung upside down from the world tree, Yggdrasil, for nine days and nine nights. It is essential to understand that runes are not and were not simply signs that could be manipulated to form language, although they certainly were used for that purpose. Runes have always been magical powers in and of themselves. They disclose hidden truths, they protect buildings, they form spells. They are the force behind what words they speak.

Since Odin found the runes while tied to the tree but did not invent them, we have to look deeper for their source. The deities who nourish Yggdrasil are the Norns Urd, Verthandi, and Skuld. They are the Norns we are usually talking about when we say “The Norns.” The Norns water Yggdrasil’s roots from a pool of water at the base of the tree. They are responsible for giving each person their destiny and can reveal the past, present, and future. They are usually the powers invoked when using runes for divination and they are the powers petitioned for changing life circumstances. In addition to tending the tree, the Norns tend a pair of swans who are said to be the parents of all swans in the world. The Norns themselves wear cloaks of swan feathers.

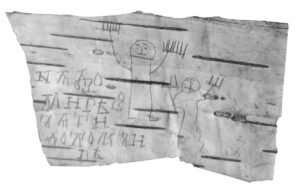

Another Germanic divinatory goddess is Frigga, who knows the future but seldom speaks of it. According to some sources it is she who bestows destiny on every child. Frigga’s distaff is in heaven and the stars revolve around it, which means she controls the calendar. Frigga wears a crown of heron feathers. Her sacred tree is the birch, probably the White Birch or Silver Birch. The white, supple bark of the birch has been used throughout northern Europe as a medium for writing and drawing. Natives in North America used the Paper Birch for similar purposes. Since bark is a degradable material it would be impossible to know how far back symbolic drawing on birch goes; extant pieces from Russia date to the twelfth century. Not much was recorded in Christian times about Frigga, despite her status as nominal head of the pantheon along with Odin, because clerics worked especially hard to erase all traces of her. Those who in later centuries recorded the Norse legends were men who would not have been privy to feminine traditions anyway. While Frigga is not explicitly documented as a writing goddess, information about her points in that direction.