Leaves finally came out this week, in literally two days.

Open water everywhere now! I’ve been hearing Canada Geese from my apartment for weeks. With the reduced traffic from COVID-19 lockdowns, I wonder if even people in the cities can hear them. When I lived in Arizona, they flew so high during migration that they looked like swarms of gnats.

Tired of looking at cats on the Internet? Here’s a duck.

There’s actually a female Mallard nearby in this photo, but she’s impossible to see with her camouflage coloring. Though males are more colorful, females are more vocal.

The Mallard is the most common wild duck, ancestor of the domestic white, found throughout the Northern Hemisphere with slight variations in coloring. This male has a lot of white on its body and a reddish belly and might be confused with a Merganser, also common in this area. The female confirms the identification.

“Like a duck to water,” goes the saying. I took this sighting as a message of being in one’s own element, feeling natural, effortless, and in control.

On an electric pole along the Ausable River, between the villages of Jay and Ausable Forks, I saw a pair of nesting ospreys on Wednesday. They’ve picked this particular site before, and the region experienced a half-day planned electricity outage last year as crews tore down the nest after the chicks were grown. Looked on the map and noticed a pond in a housing development, which may be stocked, flows into the river near this site.

This video, which is amazing, is not the electric pole in question. These birds eat a LOT of fish. They can pull bigger fish than shown here out of the lakes in the Adirondacks.

I’ve been trying to learn to differentiate Osprey, Pileated Woodpecker, Northern Flicker, and Northern Goshawk calls. Sounds doable when comparing recordings, but in the field it’s a bit more challenging.

As you cozy into your COVID cocoon, snug as a bug in a rug, now’s the time to think about crocodiles. They can’t get you now – you’re inside!

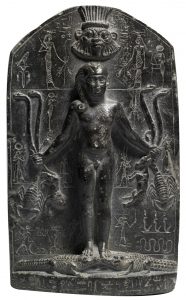

In Ancient Egypt that might not have helped, because crocodiles were kept as pets. They wore jewelry and had special piercings to display their jewelry. Crocodile Body Piercer: there’s a high risk occupation. I wonder if it was considered “essential business” during a fever epidemic. You can bet the Egyptians didn’t close the houses of worship for a little plague. They would be earnestly supplicating the divine temple crocodile Petsuchos – a living, breathing god incarnate – for relief.

River crocodiles are wily hunters who have been observed hunting in tandem. Sometimes they cower with brush on their snouts hoping to lure birds seeking nesting materials. They have good memories and monitor the routines of prey animals. Crocodiles clamp their victims in powerful jaws and hold them underwater until they drown. (Crocs themselves can stay underwater several hours.) Then they dismember the bodies by thrashing in the water until the pieces are small enough to swallow.

Crocodiles lay their eggs on land near water and cover them with grass, mud, or sand to protect from the heat. Then the mother crocodiles rest close by to guard the nest. When the babies are ready to hatch, they mew inside their eggs. As they emerge, the mother carries them in her snout to the water. She will protect them from predators while they are small.

Crocodilians have a lot of patience, and spend much of their lives waiting around for eggs to hatch or a meal to appear. This is a magical quality in much demand at the moment, as we wait for the pandemic to subside. More crocodile magic can be found in my book Divining with Animal Guides.

Anyone else notice attacks on their website decrease significantly during the Chinese New Year? The Chinese and Russian governments pay the most attention to this site. I don’t flatter myself that they’re reading it; I think it’s a policy of overall nuisance and mischief, not directed at me personally.

I’ve been listening to Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill on audio, about Harvey Weinstein’s predatory sexual criminality. I hesitated ordering it, figuring it would make me mad, and it has, but it’s been interesting too. It struck me how hard it can be to understand the potential of a project to change things while it’s underway.

The other thing that struck me was how much better and more explosive the story became as a result of efforts of NBC executives to kill the story. They kept telling Farrow he didn’t have enough evidence, and he kept digging, I guess because he didn’t realize he was being played as a sap. It reminds me of the fairy tales, where the heroine is given some impossible task, like “bring me bones from the witch Baba Yaga’s hut,” as a way of getting rid of the naive heroine, and then she actually performs the mission. The evil stepmother rages, sends her out on another task designed to fail, and the heroine returns successful.

What’s really felt weird has been reading about the trial that’s happening this week in New York City while listening to this book. Weinstein is pleading “not guilty” to rape charges and the witnesses are different than the ones mentioned in the book. The guy certainly was busy.

A misconception emerged in the last decade of the twentieth century that took feminism seriously off track: the assertion that feminism is about “the rights of everyone.” Yes, because feminism deals with the rights of half the world’s population, it has had to delve into many issues that also affect men, albeit in different ways. Feminism has had to address racism, as it affects women of color. Feminism has had to address class, as it affects working class women. Feminism has had to address sexual orientation, as it affects lesbians. But these and other serious problems also need to be addressed within their own movements, in work performed by women and men: it is not the business of feminism to solve all the world’s problems. The moment women ceased to be centered in the movement dedicated to furthering their rights, feminism itself became a tool for placing women last.

Since feminism has never been popular, it’s debatable whether defining feminism as “about everybody” has done anything for other movements. Defining a problem as a “women’s issue” at best frames it as a problem for women to solve. Since women as a group lack political and economic power, while shouldering most of the daily work of taking care of others, the group with the least resources is tasked with solving the biggest problems. Certainly women should be part of these solutions, but they are men’s problems, too, and men need to give in real ways, not just in empty grandstanding.

Making feminism about everybody’s rights does make feminism slightly more fashionable. A feminism about “men too” is a feminism more men and women can get behind. And since men’s ideas and needs are the draw for the “everybody feminism,” men quickly become the priority. Feminism that centers men is (mistakenly) lauded as “intersectional.” Feminism that centers women, such as childbirth issues, is decried as “white feminism,” although childbirth can transcend “white feminism” by reframing it in terms of those identifying as men: chest feeding, not breastfeeding; front hole, not vagina; pregnant person, not mother. At worst, “everybody feminism” destroys the concept that there can be a legitimate movement centered on women’s rights.

Feminists who are for women have grown increasingly weary of “everybody feminism,” cognizant of the deleterious effects of feminist mission creep on the women’s movement. Nowhere has this mission creep been more obvious than in the assertion that “animal rights are a feminist issue.”

Feminism is a movement concerned with the rights of women – adult human females. By definition, it is not about nonhuman animals. The rights of animals are important – with the growing eradication of whole species it can be argued that animal rights are more important than those of women – but animal rights are not the same as women’s rights.

The exploitation of animals in capitalism is indefensible. Eating animals can be defended as the cycle of life or decried as unnecessary for human survival, but the wrongness of inflicting suffering on animals should be a given. There is also overwhelming evidence that exploitative practices of the meat industry contribute greatly to global warming and other environmental pollution. The question for people invested in the wellbeing of animals (and the planet) is not whether animals are exploited by humans but how to reduce or eliminate that exploitation.

Actually, there is an additional question: how to define that exploitation. The suffering of animals at human hands is so ubiquitous that you would think this definition would be obvious, or at least that debate over the finer points could be put aside until gross injustices are remedied. But there is a tendency in social movements to equate the suffering of one constituency with that of another, one in which there is seemingly more agreement. This tendency is especially prevalent when activists feel their efforts are being stymied. When people feel like they are losing an argument, they bring up such an analogy – not to gain insight into their issue or to explain their position, but to win the debate.

The most famous example of this tendency is Godwin’s Law, the observation that any passionate sustained argument will eventually devolve into a comparison with The Holocaust. Another common occurrence brings Segregation in the South into arguments that have nothing to do with race. Then there is Sexual Violence Against Women. Apparently it happens to animals too.

To people who use these analogies, the parallels are obvious. There is hierarchy and violence; there is domination and abuse; there is perpetration and suffering. But analogies are not equations. People who use human rights analogies need to think about where these analogies break down.

Infringement on animal rights predates patriarchy. I would guess (without really knowing) that abuse in 10,000 B.C.E. was milder than today, but at the end of the Ice Age many species of mammals were hunted by humans into extinction, and not always because there were no alternatives. Humans moved to a more plant-based diet partly because we had killed so many animals (though the environmental changes precipitated the imbalance).

Animal abuse does not, usually, involve sexual gratification. Yes, men can do all kinds of bizarre sexual things, but the key word is bizarre. Bestiality is not normative male behavior, unlike sexual abuse of women.

Animal abuse occurs across species. Animal rights activists are often criticized for caring about animals yet not caring about people. Sometimes this accusation is justified, sometimes it is not, but it is an obstacle in convincing the public to refrain from supporting factory farming. Occasionally I see social media bios that say something like, “I love animals and hate people.” I wonder, do the owners of these accounts understand that dogs and cats are not reading their Facebook posts? Do they think that kind of post endears them to other humans (unless those humans are so delusional they believe they are nonhuman animals)? Do they understand what it means to be human, and can a person who doesn’t understand humans think about animal rights in a coherent way?

One argument for animal rights as feminism uses a Marxist analysis of ownership of female reproduction. The idea is that, just as patriarchy controls women’s reproduction, animal abuse is about controlling the fertility of female animals. This, to me, is a stretch. Yes, domestic female animals are used for their eggs and milk. Every animal slaughtered is some female’s baby. But I don’t think female animals, on balance, are really treated worse than males. In the rural community where I live, which is very patriarchal, the marginal agricultural environment supports goats and sheep, and the females are well cared for. The males, of no use for wool or milk, are made into burgers. Male deer are hunted and does are left alone. Dogs and cats are not pampered according to sex, but male horses are usually castrated. I’m sure there are examples of female animals treated worse or suffering more than males, but as a country girl I’m finding this a hard sell.

Women’s right are human rights. They’re not animal rights.

The false equivalency between women’s and animal rights movements has produced a backlash that is in some way understandable. This should not mean, however, that feminism should leave animal rights alone. When feminist events become inhospitable to animal rights activists, it does become an issue specifically for feminists. I’ve noted situations where multi-day feminist events did not offer vegan options, either as part of the pre-paid event meals or as option to buy elsewhere in vegan food deserts. Since veganism is an important aspect of animal rights for many women, this becomes a feminist issue in terms of barriers.

There are a lot of “feminist” issues that are not intrinsically about women’s rights. Women in literature has been recognized from the start feminist issue, with women’s words suppressed or warped by patriarchy. Women in STEM is a hot feminist issue right now, with feminists pushing to overturn barriers for girls entering science and tech fields. Yet science is not intrinsically about women’s rights; it only affects our rights tremendously. Women and religion is another important area for feminists, yet is religion itself about women’s rights, or it only used as a tool for perpetuating male dominance?

Animal rights is a women’s issue when it is an issue begging for feminist leadership and influence. Animal rights as practiced can have a “ladies’ auxiliary” aura to it, with men defining and controlling the issue and women preaching to other women about becoming vegan to be a real feminist. It reminds me of knitting socks to help the war effort. Who controls the philosophy of animal ethics, or the strategy of animal rights, and why?

There has also been an element (which may now be on the wane) of the subjugation of women through animal rights activism. I’m talking about the PETA lettuce dresses and other skimpy clothing, the women re-enacting lobsters boiling, the women subjecting themselves to animal testing. This kind of “activism,” whether promoted by women or men, has used animal rights to express hatred and objectification of women. Young women, motivated by compassion for animals, have found themselves conned by this movement. I believe that in some instances animal rights has been used as an issue to control women.

Animal rights need to be discussed within feminism, not as part of the to-do list of being a feminist, but for feminist influence in a wider movement. Why is being vegan an issue for feminists, when men eat so much more than we do? Shouldn’t they be the focus of dietary changes?

Anything can really be about feminism, but the way we know if we are practicing real feminism, versus “everybody feminism,” is by looking at how that feminism challenges the power of men. Are animal rights a feminist issue? Only as they intersect with women’s rights. Only as they affect women’s right to influence an important issue. Only as they may be used by men to dominate women. Animal rights should, in the end, be focused on animals, and there are problems with grafting a human rights model onto animals. Sometimes we have to look beyond our anthropomorphic lens.

So these are the ways animal rights becomes a feminist issue: 1) Ensuring there are no barriers to participation by vegan women in feminism; 2) Pushing for meaningful participation by feminists in the animal rights movement; and 3) Countering the way the animal rights movement is used to further subjugate women. To base analysis of the subjugation of animals on the subjugation of women, however, is unhelpful. Most people, men and women, care less about the suffering of women than that of animals, and making animal rights about feminism extends the mission creep of “everybody feminism” from men to animals.

There is a 3-legged deer in the village that has attained almost mythical status. People who spot the deer limping around at night are alarmed, only to be reassured that, “Yeah, she’s missing part of a front leg, but she gets along okay. Been that way for a while.”

The other night I glanced up and saw the 3-legged deer peering in the window at me. Wildlife, mostly deer, do this, and I feel sometimes like my house is a zoo cage and I’m on display for the wildlife.

I learned last night that our gimpy deer is not a doe, but a buck. He has a small rack going. I don’t see many bucks around, because they are hunted and they don’t have antlers much of the year. The 3-legged buck stood awhile at the window and then limped away.

Yes, the Bald Eagle is the US national bird, but I’ll bet you secretly like the Wild Turkey best.

Though once endangered, the Wild Turkey has made a comeback and is found in most US states (and in northern Mexico). In New England, she has become a bit of a nuisance, flocking onto roadways and chasing suburban children.

Turkeys are social animals, the females at least, and sisters sometimes raise their next brood together. They can be aggressive, which makes sense, since their chicks are grounded. Adult turkeys can fly and swim, though they usually choose to run and walk.

They are quite fast runners. Once a turkey challenged me to a race. I was riding my bicycle on a paved country road, and a turkey began trotting next to me. Just for fun, I sped up, and the turkey continued running alongside of me. Finally I broke loose and pedaled as fast as I could, and the turkey and I were in tied in a fiercely competitive race. Eventually we left farmland and passed into a copse of trees, and the turkey had to fly up into the branches.

The word for turkey in Munsee Delaware is puleew, and the turkey is the totem animal for one of the major clans. Delaware women would wear cloaks of turkey feathers during important ceremonies.

The turkey has been the downfall of many a vegetarian. Many have told me that they stayed away from animal flesh completely for a year or more until one day, when they were really hungry, there was turkey….

I learned today that sharks have rather interesting vision. Many species have both rods and cones, and they demonstrate an excellent ability to detect contrast. Like cats and other night animals, sharks have a tapetum lucidum, a layer of mirror-like crystals behind the retina which enhances vision in very low light. Apparently sharks hunt primarily by sight, even though they are also sensitive to vibration, electromagnetic fields, and chemical changes in the water. Tiger Sharks have a clear membrane that can cover their eyes like a see-through eyelid while on the attack. Tiger Sharks, like tigers, are one of the few animals that view humans as food. (Great White Sharks will attack humans, but they haven’t actually acquired a taste for us.) They are predators with superb vision, particularly in the watery depths.

In my book, Divining with Animal Guides, I write about the eyesight of many animals and how that applies to divination.

Several years ago, I ran over a rabbit in the car on a lonely stretch of highway. I don’t remember what kind of rabbit; it wasn’t important at the time, probably not even to the rabbit. What mattered was that the rabbit was alive, and then it was dead.

As is typical of deserted roads in the Adirondacks, it was several miles before I could find a place to turn around, but I felt it was important to return, to take responsibility for my action, inadvertent as it was, and honor the life taken. When I returned I discovered the rabbit had hopped or been thrown to the side of the pavement, where it died. I was struck not with pity or regret or self-recrimination, but with confusion and then with wonder. Because the rabbit was not there. The body lay beside the road but the rabbit was gone gone gone. The rabbit had hopped away, with no attachment to the physical form or the place of death. Perhaps I could call its spirit back and ask forgiveness, but why do that, except to placate my own spirit? It happened. The rabbit had moved on. I needed to do the same.

I tend to think that the ease with which the rabbit slipped out the world had to do with the temporal nature of cornerstone species, their short lives making their foothold in this world a tentative one. I imagine that the long-lived elephant would leave with a long good-bye, especially from what I have read about elephant funerals and elephant graveyards. Then too, our North American leporidae are not social creatures, unlike elephants and Old World rabbits. A social hierarchy seems to anchor a species to the earth, creating as it does a more complex system of obligation.

Given the rabbit’s ease in slipping into the world of the dead, it is interesting that graveyards provide such a hospitable living environment for rabbits, hosting open grassy spaces in metropolitan or densely forested areas. While we usually think of bats and spiders at Halloween, the rabbit seems like a highly appropriate animal to meditate upon as the veil grows thin.

In my book, Invoking Animal Magic, I devote a whole chapter to folklore about rabbits and hares.