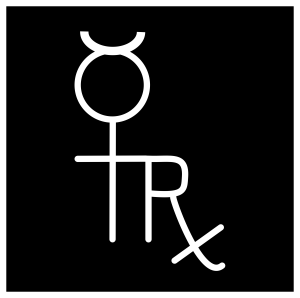

mERCURY retroGRADE

June 28, 2013 About three times a year, the planet Mercury “goes retrograde,” which means from our perspective on Earth it looks like it is changing direction in the sky, moving east-to-west instead of west-to-east. This happens because Mercury and the Earth have different orbital patterns around the Sun, the Earth’s orbit being rounder while faster-moving Mercury’s orbit is more elliptical. Although in reality Mercury is moving steadily along its path, from our vantage point on Earth, Mercury seems to speed up, slow down, remain stationary, move backwards, remain stationary, then move counterclockwise across the sky once again.Mercury is conventionally believed to be the planet ruler of money, commerce, travel, health, literature, music, math, media, communication, technology, and mechanical objects. You might be wondering, what else is there? Well, there’s love, power, conception, parenting, values, death, grandparents, the occult – lots of stuff. But in modern Western society day-to-day survival depends upon the things that Mercury “rules.” Thus when Mercury does something dramatic, like change direction, we would expect it to have immediate noticeable effects.Astrologers disagree on what Mercury retrograde means, but all agree that its effects are significant. Conventional wisdom says that during Mercury retrograde it is more likely that cars will break down, mistakes in computation will occur, miscommunications will happen, health problems will become manifest, etc., etc. Often a period of meditation is prescribed while Mercury is retrograde, but I have found my meditation to be less focused and less productive during this time.I believe that in a general way Mercury influences productivity, however productivity is defined by the individual or society, and that when Mercury changes direction there is a shift in focus. Usually that shifting focus is towards something that has been neglected. This is why mechanical breakdowns and health concerns command attention for some during this time. This does not necessarily mean that the individual has been doing something “wrong”: attention cannot be spread everywhere at all times.The symbol for retrograde in astrology is Rx, which is also the symbol for a medical prescription. This is how I look at a retrograde, as a prescription for a problem, error, disease, or unknown need. In practical terms this can manifest in outward events that demand that we turn our attention to things we have deemed unimportant, like sleep or play, but often the effects are more subtle. We may naturally find ourselves catching up on reading, cleaning out a closet, or spending time in meditation.Under this interpretation of Mercury and Mercury retrograde, the difficulties I have had with meditation at this time make sense. Since meditation was something I found time for under normal circumstances, my attention needed to shift temporarily to other matters.Ultimately the seemingly unproductive downtime of Mercury retrograde keeps us moving toward our goals. Think of it as maintenance and accept the shift in focus, whether it comes from within or without.

About three times a year, the planet Mercury “goes retrograde,” which means from our perspective on Earth it looks like it is changing direction in the sky, moving east-to-west instead of west-to-east. This happens because Mercury and the Earth have different orbital patterns around the Sun, the Earth’s orbit being rounder while faster-moving Mercury’s orbit is more elliptical. Although in reality Mercury is moving steadily along its path, from our vantage point on Earth, Mercury seems to speed up, slow down, remain stationary, move backwards, remain stationary, then move counterclockwise across the sky once again.Mercury is conventionally believed to be the planet ruler of money, commerce, travel, health, literature, music, math, media, communication, technology, and mechanical objects. You might be wondering, what else is there? Well, there’s love, power, conception, parenting, values, death, grandparents, the occult – lots of stuff. But in modern Western society day-to-day survival depends upon the things that Mercury “rules.” Thus when Mercury does something dramatic, like change direction, we would expect it to have immediate noticeable effects.Astrologers disagree on what Mercury retrograde means, but all agree that its effects are significant. Conventional wisdom says that during Mercury retrograde it is more likely that cars will break down, mistakes in computation will occur, miscommunications will happen, health problems will become manifest, etc., etc. Often a period of meditation is prescribed while Mercury is retrograde, but I have found my meditation to be less focused and less productive during this time.I believe that in a general way Mercury influences productivity, however productivity is defined by the individual or society, and that when Mercury changes direction there is a shift in focus. Usually that shifting focus is towards something that has been neglected. This is why mechanical breakdowns and health concerns command attention for some during this time. This does not necessarily mean that the individual has been doing something “wrong”: attention cannot be spread everywhere at all times.The symbol for retrograde in astrology is Rx, which is also the symbol for a medical prescription. This is how I look at a retrograde, as a prescription for a problem, error, disease, or unknown need. In practical terms this can manifest in outward events that demand that we turn our attention to things we have deemed unimportant, like sleep or play, but often the effects are more subtle. We may naturally find ourselves catching up on reading, cleaning out a closet, or spending time in meditation.Under this interpretation of Mercury and Mercury retrograde, the difficulties I have had with meditation at this time make sense. Since meditation was something I found time for under normal circumstances, my attention needed to shift temporarily to other matters.Ultimately the seemingly unproductive downtime of Mercury retrograde keeps us moving toward our goals. Think of it as maintenance and accept the shift in focus, whether it comes from within or without.

Solstice Moon

June 21, 2013 This Friday, June 21st, at 12:04 AM Eastern Daylight Time (5:04 Universal Time) the sun reaches the northernmost point in her travels, marking the Summer Solstice. Of course, the sun isn’t really moving north; the northern hemisphere of the earth is tilting toward the sun and will begin a reciprocal tilt following the solstice. But from our perspective, the sun has come to the north. This is a high energy time, wonderful for spell work or for group ritual. Traditionally this is the time when covens that have “hived off” to form their own groups return to the mother coven for reunion. Interestingly, it is not the midday zenith of the sun that is considered the most auspicious but rather the short twilight night.On Sunday morning at 7:32 AM Eastern Daylight Time on June 23rd, we have the full moon in June. The June full moon is always special. Women used to gather dew from the leaves of the trees just before sunrise at June’s full moon to use in their spells. This dew is potent for love charms or anything that the heart desires. This full moon arrives twenty-two minutes after the moon is at perigee, the nearest point in her orbit around the earth. At perigee the moon’s influence is obviously stronger, so a full moon at perigee is very powerful.In the past I have expressed skepticism over certain dates that are promoted as unusually auspicious times for doing magic, but this weekend really is a big deal. The perigee full moon occurring so close to the Summer Solstice makes this an extremely powerful time for magic. Analyzing the various factors involved (waxing versus waning moon, astrological sign of the moon, moon void-of-course, and proximity to the solstice or full moon), I would say that the evenings of Friday June 21st, Saturday June 22nd, and Sunday June 23rd are about equally powerful for those living in North America, although I lean very slightly in favor of Saturday the 22nd. If you live on the West Coast, I would recommend a specific time for ritual: that would be during the very early morning hours of June 23rd between 1:10 AM and 1:30 AM Pacific Daylight Time. At this time the moon has entered Capricorn, the astrological sign of her fullness, and the sun will be at her nadir.Since Mercury is getting ready to go retrograde, don’t expect the results of your spells to manifest immediately. Project your energy toward attaining goals that can come to fruition toward the end of the summer or later.If you live in the southern hemisphere, this Winter Solstice weekend is also powerful for magic. The energies particularly favor the beginning of new projects and (metaphorically) the planting of new seeds.

This Friday, June 21st, at 12:04 AM Eastern Daylight Time (5:04 Universal Time) the sun reaches the northernmost point in her travels, marking the Summer Solstice. Of course, the sun isn’t really moving north; the northern hemisphere of the earth is tilting toward the sun and will begin a reciprocal tilt following the solstice. But from our perspective, the sun has come to the north. This is a high energy time, wonderful for spell work or for group ritual. Traditionally this is the time when covens that have “hived off” to form their own groups return to the mother coven for reunion. Interestingly, it is not the midday zenith of the sun that is considered the most auspicious but rather the short twilight night.On Sunday morning at 7:32 AM Eastern Daylight Time on June 23rd, we have the full moon in June. The June full moon is always special. Women used to gather dew from the leaves of the trees just before sunrise at June’s full moon to use in their spells. This dew is potent for love charms or anything that the heart desires. This full moon arrives twenty-two minutes after the moon is at perigee, the nearest point in her orbit around the earth. At perigee the moon’s influence is obviously stronger, so a full moon at perigee is very powerful.In the past I have expressed skepticism over certain dates that are promoted as unusually auspicious times for doing magic, but this weekend really is a big deal. The perigee full moon occurring so close to the Summer Solstice makes this an extremely powerful time for magic. Analyzing the various factors involved (waxing versus waning moon, astrological sign of the moon, moon void-of-course, and proximity to the solstice or full moon), I would say that the evenings of Friday June 21st, Saturday June 22nd, and Sunday June 23rd are about equally powerful for those living in North America, although I lean very slightly in favor of Saturday the 22nd. If you live on the West Coast, I would recommend a specific time for ritual: that would be during the very early morning hours of June 23rd between 1:10 AM and 1:30 AM Pacific Daylight Time. At this time the moon has entered Capricorn, the astrological sign of her fullness, and the sun will be at her nadir.Since Mercury is getting ready to go retrograde, don’t expect the results of your spells to manifest immediately. Project your energy toward attaining goals that can come to fruition toward the end of the summer or later.If you live in the southern hemisphere, this Winter Solstice weekend is also powerful for magic. The energies particularly favor the beginning of new projects and (metaphorically) the planting of new seeds.

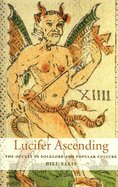

Review: Lucifer Ascending by Bill Ellis

June 14, 2013 I picked up this book written by an academic active in Lutheran ministries because the author and I share an uncommon belief: that the West has never been thoroughly Christianized and pagan “superstitions” continue to operate in plain view. Bill Ellis’ examples on this subject are much closer to orthodox ideas of the occult then mine would be, including things like formal ritual magic, Satanic “bibles,” ghost stories, and graveyard encounters with the supernatural. My examples would be more banal, including things like healing charms, housecleaning rituals, garden planting, and signs regarding true love. Yet even keeping his examination of magic to the narrow scope that meets Christian definitions of diabolical, Ellis finds no shortage of material.The inspiration for this treatise appears to be the high level of concern in fundamentalist circles generated by the Harry Potter books, which Ellis believes is misplaced. He places the tenets of the Hogwarts School in historical context and argues, “witchcraft, magical ritual, and contact with the supernatural constitute stable and generally functional folk traditions in cultures in both Europe and North America, up to the present day.” Ellis explores folk magic and legend of the past 300 years with more emphasis on German and Pennsylvania Dutch practices than I have seen elsewhere, and he also gives a nod to the prevalence of hoodoo. For this reason many students of witchcraft will find it useful in providing historical background. Ellis provides interesting theories about the function of witchcraft beliefs in Christian society and the reasons for authoritative suppression of witchcraft. Some of these motivations for suppression, such as patriarchal monopoly of medicine or legal control of marginalized people, will be familiar to many. One which was new to me has to do with the fundamentalist view of Christianity as a force for good that is opposed to witchcraft as the force of evil. Some Christians need to view witches as malignant evil-doers because that belief conforms to their world view and affirms that their own monopoly on goodness. The supposition that “a good witch is worse than a bad witch,” expressed in the Roman Catholic theology which laid the groundwork for the witch hunts, is generally believed by Pagans to reflect the desire of the church to hold monopoly over magic and ritual and to wrest power from women and the lower classes. But this may not be the issue operating in present day clashes between witches and fundamentalists. If certain Christians are determined to view themselves as stalwart goodness in a world of evil, then the presence of malignant witches is reassuring and the presence of good witches is profoundly unsettling. With fundamentalists of this stripe, pagan anti-defamation campaigns to show the world that “we’re really good people” will not meet with success and will even precipitate greater opposition.Ellis devotes considerable space to Satanic escapades of teenagers which range from possession of Anton LaVey’s Satanic Bible to summoning witches or ghosts in order to curse them to vandalizing graveyards. He argues that these are expressions of rebellion arising from the disempowerment of youth, using the “demonic possessions” of the girls in Salem Village which precipitated that late seventeenth century American witch craze as an example. I would agree that obtaining a copy of a book entitled Satanic Bible is an act of rebellion, and the girls in Salem Village may have been acting out of their disempowerment, but many of these Satanic activities strike me as reinforcing of Christian beliefs. The cursing of witches and the vandalism of graveyards expresses disaffection and hostility in a socially conforming way. I would place these actions in a category with gay bashing or desecration of synagogues. If rebellion and defiance is the motive, why not vandalize a church? Churches are occasionally vandalized by teenagers, of course, but these churches tend to be African-American, which supports my take on the issue.The role of women in the early beginnings of the Pentecostal movement, and how that movement co-opted elements of spiritualism and magic, I found fascinating. Ellis explains, “The revival expressed itself from the start as being in some palpable sense governed by supernatural forces.” He contends, “Revivalist movements likely do not produce cycles of supernatural or demonic phenomena, but they do provide ready opportunities in group meetings for people to describe their experiences and fit them into a shared mythology.” Within the context of a new religious movement women found opportunities for leadership that had been denied to them in more orthodox religious settings. One leader, Jesse Penn-Lewis, described the opposition to evangelical women’s ministries as “war by Satan upon the womanhood of the world.” It seems women have typically been at the forefront of new religious movements, from early Christianity to the Pentecostals, only to find themselves in subordinate positions again once these movements solidified.Lucifer Ascending is more evenhanded and better researched than most books dealing with witches coming out of the academic presses, and I think it adds to the social discourse on witchcraft. Even real witches are not always aware of how pervasive witchcraft is.

I picked up this book written by an academic active in Lutheran ministries because the author and I share an uncommon belief: that the West has never been thoroughly Christianized and pagan “superstitions” continue to operate in plain view. Bill Ellis’ examples on this subject are much closer to orthodox ideas of the occult then mine would be, including things like formal ritual magic, Satanic “bibles,” ghost stories, and graveyard encounters with the supernatural. My examples would be more banal, including things like healing charms, housecleaning rituals, garden planting, and signs regarding true love. Yet even keeping his examination of magic to the narrow scope that meets Christian definitions of diabolical, Ellis finds no shortage of material.The inspiration for this treatise appears to be the high level of concern in fundamentalist circles generated by the Harry Potter books, which Ellis believes is misplaced. He places the tenets of the Hogwarts School in historical context and argues, “witchcraft, magical ritual, and contact with the supernatural constitute stable and generally functional folk traditions in cultures in both Europe and North America, up to the present day.” Ellis explores folk magic and legend of the past 300 years with more emphasis on German and Pennsylvania Dutch practices than I have seen elsewhere, and he also gives a nod to the prevalence of hoodoo. For this reason many students of witchcraft will find it useful in providing historical background. Ellis provides interesting theories about the function of witchcraft beliefs in Christian society and the reasons for authoritative suppression of witchcraft. Some of these motivations for suppression, such as patriarchal monopoly of medicine or legal control of marginalized people, will be familiar to many. One which was new to me has to do with the fundamentalist view of Christianity as a force for good that is opposed to witchcraft as the force of evil. Some Christians need to view witches as malignant evil-doers because that belief conforms to their world view and affirms that their own monopoly on goodness. The supposition that “a good witch is worse than a bad witch,” expressed in the Roman Catholic theology which laid the groundwork for the witch hunts, is generally believed by Pagans to reflect the desire of the church to hold monopoly over magic and ritual and to wrest power from women and the lower classes. But this may not be the issue operating in present day clashes between witches and fundamentalists. If certain Christians are determined to view themselves as stalwart goodness in a world of evil, then the presence of malignant witches is reassuring and the presence of good witches is profoundly unsettling. With fundamentalists of this stripe, pagan anti-defamation campaigns to show the world that “we’re really good people” will not meet with success and will even precipitate greater opposition.Ellis devotes considerable space to Satanic escapades of teenagers which range from possession of Anton LaVey’s Satanic Bible to summoning witches or ghosts in order to curse them to vandalizing graveyards. He argues that these are expressions of rebellion arising from the disempowerment of youth, using the “demonic possessions” of the girls in Salem Village which precipitated that late seventeenth century American witch craze as an example. I would agree that obtaining a copy of a book entitled Satanic Bible is an act of rebellion, and the girls in Salem Village may have been acting out of their disempowerment, but many of these Satanic activities strike me as reinforcing of Christian beliefs. The cursing of witches and the vandalism of graveyards expresses disaffection and hostility in a socially conforming way. I would place these actions in a category with gay bashing or desecration of synagogues. If rebellion and defiance is the motive, why not vandalize a church? Churches are occasionally vandalized by teenagers, of course, but these churches tend to be African-American, which supports my take on the issue.The role of women in the early beginnings of the Pentecostal movement, and how that movement co-opted elements of spiritualism and magic, I found fascinating. Ellis explains, “The revival expressed itself from the start as being in some palpable sense governed by supernatural forces.” He contends, “Revivalist movements likely do not produce cycles of supernatural or demonic phenomena, but they do provide ready opportunities in group meetings for people to describe their experiences and fit them into a shared mythology.” Within the context of a new religious movement women found opportunities for leadership that had been denied to them in more orthodox religious settings. One leader, Jesse Penn-Lewis, described the opposition to evangelical women’s ministries as “war by Satan upon the womanhood of the world.” It seems women have typically been at the forefront of new religious movements, from early Christianity to the Pentecostals, only to find themselves in subordinate positions again once these movements solidified.Lucifer Ascending is more evenhanded and better researched than most books dealing with witches coming out of the academic presses, and I think it adds to the social discourse on witchcraft. Even real witches are not always aware of how pervasive witchcraft is.

Lily of the Goddess

June 7, 2013

The Hand of Kwan Yin

May 31, 2013 This is the statue of the goddess Kwan Yin which I have on my altar. It was given to me by a student after my first Kwan Yin statue was broken by my cat – not Samhain, the cat I had before her, Misha.I was very grieved by the loss of this statue, not only because Kwan Yin is an important goddess to me, but because the statue was given to me by a good friend I had lost touch with. Someone explained to me, however, that porcelain statues of Kwan Yin are expected to break eventually, and that I should take the statue to a temple rather than dispose of it myself.Knowing how devastated I was by these events, one of my students was excited to find a statue she thought was Kwan Yin at a garage sale. “I don’t know if this is Kwan Yin but I thought it might be,” she said. “But there’s a hole in it where one of the hands should be. We’ve been trying to figure out what that’s for.” I knew exactly what the hole was for, because my first statue had the same feature. The hole is for a detachable hand that is removed from the statue when making a request. The supplicant carries the hand around with her until the prayer is granted, then returns it to the goddess.Kwan Yin is the Chinese Buddhist goddess of mercy, “She who hears the cries of the world.” She is a complex and multifaceted goddess who has been the subject of much scholarship, particularly with the rebirth of the Goddess Movement. Even before this she had a sizable devoted following, among Westerners as well as Chinese. I first heard about Kwan Yin at a lecture given by the editor of a paper I worked on, Libby Gregory. In the dark ages before videos and the Internet, Midwesterners went to lectures for entertainment. I don’t know if it was a product of the big tent Christian revival experiences of the audience or if this is a common experience during discussions of Kwan Yin, but after Libby’s talk many people came forward and shared their miraculous experiences with Kwan Yin’s intervention. I was impressed.Because she introduced me to Kwan Yin, my feelings about this goddess are intertwined with my feelings about Libby. A small business owner and editor of the local left-wing paper, Libby was a driving force behind the progressive movement in our conservative town. To be honest I often thought of her as a bit of a nuisance, frequently calling me on the telephone requesting my services for hard journalistic assignments requiring a great deal of investigation. For some reason I almost always said yes, even though these assignments offered very little pay. It was another Kwan Yin miracle.Eventually I moved away to the West Coast and didn’t think too much about Libby. I liked her, but I certainly didn’t give her my new phone number. It was when I was back for one of my infrequent visits that I learned Libby had died several years earlier, killed in a plane crash. Although Libby had never been a huge figure in my personal life, I could not imagine the town without her. She was like the Olentangy River or the state university campus – she was a part of the community structure. Her loss left a hole that could not be replaced.It did not surprise me to learn that “killed in a plane crash” only told part of the story. Libby had stayed behind to help other passengers as the smoking plane was being evacuated, and so was one of the few who did not survive. We could wish she had left the burning aircraft while she had a chance, but if she had done that she wouldn’t have been the person she was.When I was ordained in the Fellowship of Isis, I was asked to make a pledge to three goddesses, one of which I would be “priestess of” and two more I would agree to serve. I chose Kwan Yin as one of my three goddesses. Not because of Libby exactly, but because of mercy.My student took the statue back home and asked her woodworking husband to make a new hand for it. I’ve always wondered about the missing hand, if someone prayed for something they wanted very much and the request was never granted. I hope by this time they have found recompense for their loss.

This is the statue of the goddess Kwan Yin which I have on my altar. It was given to me by a student after my first Kwan Yin statue was broken by my cat – not Samhain, the cat I had before her, Misha.I was very grieved by the loss of this statue, not only because Kwan Yin is an important goddess to me, but because the statue was given to me by a good friend I had lost touch with. Someone explained to me, however, that porcelain statues of Kwan Yin are expected to break eventually, and that I should take the statue to a temple rather than dispose of it myself.Knowing how devastated I was by these events, one of my students was excited to find a statue she thought was Kwan Yin at a garage sale. “I don’t know if this is Kwan Yin but I thought it might be,” she said. “But there’s a hole in it where one of the hands should be. We’ve been trying to figure out what that’s for.” I knew exactly what the hole was for, because my first statue had the same feature. The hole is for a detachable hand that is removed from the statue when making a request. The supplicant carries the hand around with her until the prayer is granted, then returns it to the goddess.Kwan Yin is the Chinese Buddhist goddess of mercy, “She who hears the cries of the world.” She is a complex and multifaceted goddess who has been the subject of much scholarship, particularly with the rebirth of the Goddess Movement. Even before this she had a sizable devoted following, among Westerners as well as Chinese. I first heard about Kwan Yin at a lecture given by the editor of a paper I worked on, Libby Gregory. In the dark ages before videos and the Internet, Midwesterners went to lectures for entertainment. I don’t know if it was a product of the big tent Christian revival experiences of the audience or if this is a common experience during discussions of Kwan Yin, but after Libby’s talk many people came forward and shared their miraculous experiences with Kwan Yin’s intervention. I was impressed.Because she introduced me to Kwan Yin, my feelings about this goddess are intertwined with my feelings about Libby. A small business owner and editor of the local left-wing paper, Libby was a driving force behind the progressive movement in our conservative town. To be honest I often thought of her as a bit of a nuisance, frequently calling me on the telephone requesting my services for hard journalistic assignments requiring a great deal of investigation. For some reason I almost always said yes, even though these assignments offered very little pay. It was another Kwan Yin miracle.Eventually I moved away to the West Coast and didn’t think too much about Libby. I liked her, but I certainly didn’t give her my new phone number. It was when I was back for one of my infrequent visits that I learned Libby had died several years earlier, killed in a plane crash. Although Libby had never been a huge figure in my personal life, I could not imagine the town without her. She was like the Olentangy River or the state university campus – she was a part of the community structure. Her loss left a hole that could not be replaced.It did not surprise me to learn that “killed in a plane crash” only told part of the story. Libby had stayed behind to help other passengers as the smoking plane was being evacuated, and so was one of the few who did not survive. We could wish she had left the burning aircraft while she had a chance, but if she had done that she wouldn’t have been the person she was.When I was ordained in the Fellowship of Isis, I was asked to make a pledge to three goddesses, one of which I would be “priestess of” and two more I would agree to serve. I chose Kwan Yin as one of my three goddesses. Not because of Libby exactly, but because of mercy.My student took the statue back home and asked her woodworking husband to make a new hand for it. I’ve always wondered about the missing hand, if someone prayed for something they wanted very much and the request was never granted. I hope by this time they have found recompense for their loss.

The Messages of Birds

May 27, 2013 Recognizing the signs of birds is one of the most ancient sciences. Another post at Return to Mago blog.

Recognizing the signs of birds is one of the most ancient sciences. Another post at Return to Mago blog.

Kitten

May 24, 2013