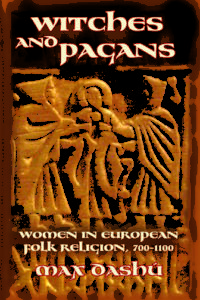

Max Dashu has posted significant excerpts of her multi volume project on the history of witchcraft at her Suppressed Histories website for years, and publication of her research in book form has been eagerly anticipated. This first installment (which Dashu refers to as Volume VII) covers the years 700 to 1100 – a good choice, because this period is critical to understanding the peak of the witch craze in late medieval and early modern times. This is also a period in European history where not a lot of information is available to the average Pagan.

Max Dashu has posted significant excerpts of her multi volume project on the history of witchcraft at her Suppressed Histories website for years, and publication of her research in book form has been eagerly anticipated. This first installment (which Dashu refers to as Volume VII) covers the years 700 to 1100 – a good choice, because this period is critical to understanding the peak of the witch craze in late medieval and early modern times. This is also a period in European history where not a lot of information is available to the average Pagan.

Dashu is explicit that she is writing for a lay audience, but this is a thoroughly researched and referenced work, with a large bibliography and over a thousand footnotes. There are some readers who will think she excessively belabors her points, but there is so much misinformation out there, often written by slipshod academics and well-intentioned Pagans who rely on these academics, that a solid scholarly work was sorely needed. The conclusions Dashu reaches will not be startling to better informed researchers inside and outside academia, but the weight of evidence on which she bases her findings is gratifying in this highly contentious field. No doubt there are many who will be surprised.

The book utilizes linguistic analysis, place names, archaeology, folk customs documented by clerics, early theological treatises on demonology and witchcraft, and mythology of pagan origin recorded by Christians. Dashu is well aware of the shortcomings of each of these methodologies and discusses them frankly. Still the amount of evidence, from many types of sources, leads to well grounded conclusions. This book mentions in passing some of the biases which hamper academic research on witchcraft, leading to often repeated yet erroneous beliefs that have seeped into Pagan discourse.

Dashu informs us that Pagan beliefs and shamanic practices not only survived well into the Middle Ages in supposedly Christianized regions, they were widespread and deeply adhered to, particularly by the lower classes. Shamanic practices and worship of goddesses and nature deities were equated with witchcraft and devil worship by clerics and formed the basis for persecution. Though trials for malefic sorcery also existed in pagan Rome, the intensity and tone of the Christian persecution was different and significantly broader, including for example healing and divination. Aristocratic government and church leadership were intricately connected and both used dispossession of pagan culture along with persecution of witches as a way of solidifying power. The healers, diviners, and keepers of tribal history known as witches were overwhelmingly female, and witch persecutions were part of a pervasive Church strategy to further subjugate women, who were already dominated by men within their pagan cultures. Dashu firmly establishes that for centuries the targets of the witch hunts were shamans, usually female, and that the purpose of witch persecutions was to establish Christian hegemony and solidify aristocratic power.

Dashu also attempts to piece together what those pagan belief systems and female shamanic practices that were under attack actually were, and here her findings must be treated as incomplete. She focuses a great deal on Germanic cultures, and practitioners of the various Germanic traditions will find a wealth of information here. She discusses the importance of the distaff in women’s mysteries and the Norse practice of “sitting out” to achieve psychic insight. She explores the little that is known about northern European goddesses. She devotes an entire chapter to the important Icelandic poem The Volupsa. This is not, however, a definitive look at any Norse tradition, and really to have attempted that would have taken this book too far afield. I have noticed a tendency in witches in my acquaintance to devote their reading solely to authors like Dashu who approach witchcraft from a solid feminist perspective. There would be nothing wrong with that if there were more Pagan writers with a true understanding of feminist theory, but there are not enough of us around to be so selective. If the material here sparks some new interest you will need to draw from a variety of sources on the runes and Norse literature. I was particularly dismayed to hear a friend say she was inclined to cut out any reference to the god Odin from her practice after reading this book. I am a Dianic priestess, and it is more than okay with me if a woman only wants to worship goddesses, but I think we must remember that male as well as female archetypes become distorted in support of male dominance. It is important that we recognize patriarchal bias in our Pagan heritage, but it is equally important that we do not stop there.

Witches and Pagans is slow reading and cannot be tackled in one or two sittings. Dashu’s writing style is clear and straightforward, but the nature of the material is that it is dense. An index would be helpful. There is a web address for an index in the book which took me to a 404 error page. There are quite a few line drawings in the book which add a great deal to the text. This is a great resource with a lot of helpful information. I hope we will not have to wait too long for the next volume of “The Secret History of the Witches.”