The vocalist on this album is from Australia, where it’s Midwinter, not Midsummer, but the track feels like a dreamy summer solstice.

A few glitches with my website last week, but everything’s fixed. I moved from one SSL provider (the thing that puts the “s” in https://) to another, and I expected some issues to arise, but they were thornier than predicted. The site was never compromised (and I’m not selling anything through this site anyway), but web browsers, especially Google, like to flag things.

Bugs have started coming out, so I don’t know how much longer I’ll be taking pictures. These are from three separate hikes this past week.

I remember my mother one day giving me this very typical (for her) advice: “Be sure to wash your celery good. I was reading the other day that celery is extremely dirty and people should be more careful.”

To which I had to reply: “Where do you read these things?”

Well, I was reading the other day that termites like heavy metal music. Yes, I read it on the Internet, but there’s so much stuff on the Internet that you have to know what to look for.

The article didn’t say whether termites show taste in heavy metal – whether they like Queen and Jethro Tull but hate KISS – but researches inferred that termites prefer this music since they chew faster when they hear it. According to Erlich Pest Control Blog, rock is ideal work music for termites due to “the frequency of 2.5KHz outputs for bass and electric guitars, which are distinctive of the rock genre.”

Mammals can have idiosyncratic tastes in music. Dolphins purportedly love Radiohead. In Tracking and the Art of Seeing, Paul Rezendes describes a raccoon who “would often come in when the man was playing Bach on his stereo. As soon as the record was over, the raccoon would leave.”

I used to have a cat who liked loud classical music, the kind with lots of horns and cymbals. She would lay next to a boombox playing Wagner or The William Tell Overture and cry if it was turned off. She’s dead now, but in Misha’s memory I would like to share this rendition of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, her favorite.

Trees are starting to bud where I live, and the birds have arrived. I went to Crown Point this week to watch the birds being banded. I’ve driven over the Crown Point Bridge hundreds of times but have never stopped here.

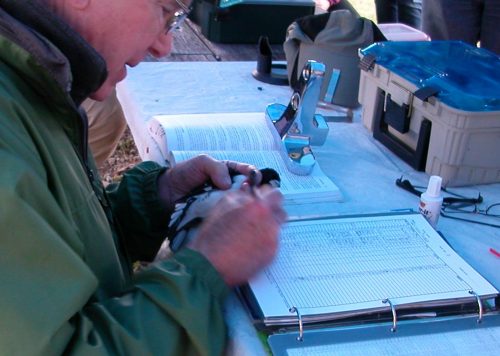

Banding a Rose Breasted Grosbeak. Birds are measured, then sex and age is recorded.

Savannah Sparrow.

It had rained early in the morning, and the cloud shapes were interesting.

After the long winters here, even dandelions are beautiful.

I liked this tree. Spring is unrolling slowly this year.

Crown Point Bridge from New York to Vermont.

It has finally begun to feel like spring where I live, even though it was snowing this morning when I arose. The trees are not leafing yet, but the maples are budding, and animal life is conspicuous. In the past week, I have seen or heard the Barred Owl, Short-eared Owl, Cooper’s Hawk, Broad-winged Hawk, Osprey, Pileated Woodpecker, and the drumming wing feathers of the courting Ruffed Grouse.

One particularly welcome sight was a Little Brown Bat that sailed by my left shoulder on a dirt road near the village. I haven’t seen spring daytime bats in years. When the Little Brown Bat emerges from hibernation, she hunts during the day for insects which are inactive at night in cool weather. I used to see groups of bats flittering in the midday sun in early spring, but that changed years ago. White-nose Syndrome was first discovered in upstate New York in 2007 and has since spread throughout North America. A few species are predicted to become extinct, though the Little Brown Bat has a chance since her numbers were so high and her colonies so widespread to begin with.

I hoped that this was a sign that the disease has run its course and the Little Brown Bat is recovering, but my Internet search only revealed that White-nose is spreading to places far from the original sighting, like southern Texas. Still, I might be one of the first to notice signs of recovery, if that is occurring. “One swallow does not a summer make,” and one bat is not a colony, but I am hopeful.

This excerpt, about meeting a cougar on a vision quest, is from Divining with Animal Guides: Answers from the world at hand.

I decided I would do a vision quest. I would go out on my own, build a fire, and instead of sleeping I would stay up all night and have visions.

I chose the dark moon for my journey. I walked a few miles along a deserted beach, with cliffs along the edge that had small caves and alcoves. When I reached a sheltered place I pulled firewood out of my backpack, gathered kindling along the beach, built a small fire, and in the approaching twilight commenced scrying into the flames. I didn’t have any visions.

I sat there a long time, getting up only to add more fuel. It began spitting rain and I became chilled even with the fire. I felt silly, shivering all by myself in a deserted place with a car less

than five miles away and a warm bed within a few hours’ drive. “This is boring,” I said to myself. I gathered my belongings and scattered the fire. As I stamped out the last embers, I had a vision.

A fat Chinese Buddha appeared, so rotund that I could not discern the outline of his body within my psychic frame of reference. I intuitively understood that he appeared to me thus to

show that he was bigger than I could envision. The limits of his influence were beyond the scope of my understanding.

The Buddha raised his hand in a gesture of protection and the apparition dissolved. I commenced my journey home.

As I trekked northward, the cliffs at my right and the ocean to my left, I discovered it was not raining at all; the fine droplets were from an unusually rough tide. How had I blotted out the sound of that surf? I realized that I was now in danger of being cut off from dry land; cliffs to one side of me with water butting up against them. Though it was very dark, I put my flashlight in my backpack because I needed both hands to scramble over the slippery rocks. I felt angry with myself for having bumbled into such a dangerous situation.

Finally the cliffs ended and the beach opened up. I had made it. I unloaded my backpack and retrieved my flashlight.

I was now only two miles from the car, two rather slow miles over sand or a short brisk walk via a trail close by. The logical option was to take the trail, but I felt an unexplained reluctance. It was one of those feelings that don’t make sense at the time, but you understand later. I was sopping wet from struggling with the surf, and I was rattled, so despite my misgivings, the trail won out.

I practically ran along the narrow path, so I was very close before I saw her. She was huge, the largest carnivorous beast I had confronted in the wild. She appeared confused. She moved a few steps from the beam of my flashlight and stood there, staring at me.

“You’re supposed to run away,” I said helpfully. The conventional wisdom was that cougars would not attack humans unless cornered, though they might possibly eat children. Many well- publicized deaths from unprovoked mountain lions have occurred since, but this was the prevailing belief at the time. I was not reassured by this while standing face-to-face with my cougar, however, because I am not a large woman. I thought to myself, “I hope this cougar understands that I’m a grown-up and not a child.”

“Listen, you’re blocking the path,” I reasoned. “Turn and follow this other path, or run back the way you came. I have to go in this direction because my car is there.”

The mountain lion took a few steps forward, slightly left of my shoulder.

“Okay, I give you the path,” I said quickly. “I’ll go another way.” I took a small step backward and shone my flashlight directly in the animal’s eyes. I took another slow step backward, and another, and another. I began shining the flashlight away, then back in her eyes, then away, then back, rationalizing this would interfere with her ability to focus. She remained still.

As I finally turned away, I let out the loudest, most terrifying scream I could muster, just to give her second thoughts about following me. “Take that, you big scream machine,” I thought.

My relationship with wilderness changed that night. After my third cougar encounter I still went out by myself, sometimes after dark, but I interacted with my environment in a different way. Hearing an unfamiliar sound I would investigate not only out of curiosity, but also out of concern for safety. I remained vigilant; I became cautious. Magical protection was no longer an abstract concept. Once there was a girl who roamed the wilderness alone at night, aware that there were mountain lions in the woods and completely unafraid. I am no longer that girl.