I’m blogging today about a piece of information about cylinder seals I ran across in a children’s nonfiction book on Mesopotamia. The book is Passport to the Past: Mesopotamia by Lorna Oakes.Cylinder seals are small cylindrical carved pieces designed to make impressions in clay. They were used in Mesopotamia to sign documents and affix ownership. Kings, officials, and just about anyone with wealth or rank had their own unique seal which they guarded carefully. These seals might be carved of ivory, shell, bone, limestone, or lapis lazuli. According to Oakes, some believe these seals evolved from sheep knuckles used for the same purpose. The book has a picture of a seal with a knob in the shape of a sheep. I could not find a public domain photo of this cylinder, but I did find another cylinder pictured here that has sheep carved into its knob.

Like a Vague Malodorous Stain Seeping into the Theological Discourse

September 12, 2014

Reflections on Recent Events in the Dianic Community

September 5, 2014

Rose of Champions

August 29, 2014

I am Nature, the universal Mother, mistress of all the elements, primordial child of time, sovereign of all things spiritual, queen of the dead, queen also of the immortals, the single manifestation of all gods and goddesses that are. My nod governs the shining heights of Heaven, the wholesome sea-breezes, the lamentable silences of the world below. Though I am worshipped in many aspects, known by countless names, and propitiated with all manner of different rites, yet the whole world venerates me…. I have come in pity of your plight, I have come to favour and aid you. Weep no more, lament no longer; the hour of deliverance, shone over by my watchful light, is at hand.

Isis then instructs Lucius to approach one of her High Priests at a procession he will be attending the next day in his captive donkey guise. The priest will be carrying a garland of roses.The next day unfolds for Lucius as Isis promised. The priest is expecting Lucius and holds the sweet garland out for the donkey to eat. Lucius is transformed back into a man, and he leaves with the entourage of Isis to be initiated as one of her priests.If you have never read The Golden Ass, the first century novel from which this story comes, I recommend that you add it to your list. Despite being informative and worthwhile ancient literature, it is an entertaining read that can also be enjoyed simply for the story. The translation by Robert Graves is considered the best.Apuleius. The Transformations of Lucius Otherwise Known as The Golden Ass. Robert Graves, trans. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1951.

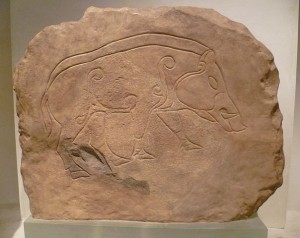

The Old Sow, part IV

August 22, 2014 The final segment of my four part series on the Sow Goddess is up at Return to Mago blog. Also see Part I, Part II, and Part III.

The final segment of my four part series on the Sow Goddess is up at Return to Mago blog. Also see Part I, Part II, and Part III.

Queen Deities and Patriarchal Distortions

August 15, 2014 As Pagans our spirituality suffers not only from the alienation from nature that is the bane of modern life, but from the class structures we struggle under. This can be seen in the way we think about and address our deities.Often when we address a nature deity which does not have a specific name, we refer to that deity as a mother, deva, goddess, or queen. For example, Hedgehog Goddess, Hedgehog Mother, Hedgehog Deva, or Hedgehog Queen. Where an animal deity is addressed by name, the name is usually the word for that animal in some non-English language, such as Arachne, which is Greek for spider, or Epona, which is a continental Celtic word for horse. Deva is borrowed from Sanskrit and is a masculine noun in that language. Mother, goddess, and queen are clearly feminine nouns and also carry the connotation of rank, privilege, or power-over.The word queen is derived from another word that means woman, which makes this word in English different from most other languages, where the word for feminine ruler is derived from a word meaning king. The word queen referring to a feminine male homosexual probably derives from the older English association with woman. The Arcade Dictionary of Word Origins says:

As Pagans our spirituality suffers not only from the alienation from nature that is the bane of modern life, but from the class structures we struggle under. This can be seen in the way we think about and address our deities.Often when we address a nature deity which does not have a specific name, we refer to that deity as a mother, deva, goddess, or queen. For example, Hedgehog Goddess, Hedgehog Mother, Hedgehog Deva, or Hedgehog Queen. Where an animal deity is addressed by name, the name is usually the word for that animal in some non-English language, such as Arachne, which is Greek for spider, or Epona, which is a continental Celtic word for horse. Deva is borrowed from Sanskrit and is a masculine noun in that language. Mother, goddess, and queen are clearly feminine nouns and also carry the connotation of rank, privilege, or power-over.The word queen is derived from another word that means woman, which makes this word in English different from most other languages, where the word for feminine ruler is derived from a word meaning king. The word queen referring to a feminine male homosexual probably derives from the older English association with woman. The Arcade Dictionary of Word Origins says:

Queen goes back ultimately to prehistoric Indo-European *gwen- ‘woman,’ source also of Greek gune ‘woman’ (from which English gets gynecology), Persian zan ‘woman’ (from which English gets zenana ‘harem’), Swedish kvinna ‘woman,’ and the now obsolete English quean ‘woman.’ In its very earliest use in Old English queen (or cwen, as it then was) was used for a ‘wife,’ but not just any wife: it denoted the wife of a man of particular distinction, and usually a king. It was not long before it became institutionalized as ‘king’s wife,’ and hence ‘woman ruling in her own right.’

The idea of Hedgehog Queen harkening back to the idea of a Hedgehog Woman reminds me of referents to spiritual or mythological beings in Native American cosmologies. I’m thinking of White Shell Woman or Changing Woman or Thunder Boy Twins. Frequently in Native American spirituality, prayers to animal deities are addressed simply to “Wolf,” “Eagle,” or “Deer.” I’m not saying Pagans should emulate this practice. Probably for anyone whose primary language is English these Native spiritual beings become processed in the brain under rubrics of “goddess,” “ruler,” or “demon” despite the democratic phraseology. It cannot be otherwise, because language reflects cultural understanding. Any animal by common name has the taint of exploitation. “Woman” carries with it connotations of inferiority and weakness, whatever our intentions and aspirations for the word. “Boy” carries with it the idea of subjugation to the man. Even the word “man” has a link with the concept of commoner or vassal, as in “my man George” or “the King’s men.”When we refer to our nature deity as “Butterfly Queen” we get around negative connotations and associations with the profane, and so to a great extent this works. It also unavoidably separates us from the deities. They are on one level; we are on another. This conundrum illustrates how it is not just patriarchal denigration of nature that has distanced us from spiritual sources, but patriarchal class structures, patriarchal authoritarian family structures, and – especially – patriarchal conceptions of women. Spiritual connection at a societal, as opposed to individual, level will require the dismantling of class structures, humane treatment of animals, recognition of children as persons with basic rights, and the liberation of women.SourcesAyto, John. Arcade Dictionary of Word Origins. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1990.Online Etymology Dictionary http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=queen (accessed 8/12/2014).

Review: A Kitchen Witch’s World of Magical Plants & Herbs by Rachel Patterson

August 8, 2014 Magical herbology is an area every witch needs to develop competency in, whatever her eventual area of focus. The challenge is to gain more than an abstract knowledge of herbs, to find opportunities for hands-on learning. A Kitchen Witch’s World includes tips on ways to work herbs into your daily life and your magical routine. Over 150 common herbs are covered, which for most witches includes all that will ever be needed. Most of the herbs are easily obtained, although one important herb – mandrake – is hard to find in the United States. (Occult stores will try to sell you mayapple as “American Mandrake” instead.) The entries for each herb are fairly short, but contain a brief description of the plant or its growing habitat, which I believe is important because most beginning witches first encounter these herbs in a package.I think what I like most about this book is that it doesn’t indulge in a plethora of correspondences. The tendency to go overboard with correspondences, to the point where it begins to inhibit learning rather than adding to it, is the bane of beginners – yet correspondences do have an important, necessary role in herb magic. I think this book sets the right balance to a thorny issue.If you already work a good deal with magical herbs, to the point where you have begun growing your own, this book is probably not for you, and if you decide to make this your area of expertise you will outgrow this book in a few years. This is not an encyclopedia, and I think we’ve come to expect the encyclopedic approach to herbs, whether for magic or healing. If you would like to use magical herbs a bit more than you do at present, this would be a good resource to have.A Kitchen Witch’s World of Magical Plants and Herbs is due out this fall and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.

Magical herbology is an area every witch needs to develop competency in, whatever her eventual area of focus. The challenge is to gain more than an abstract knowledge of herbs, to find opportunities for hands-on learning. A Kitchen Witch’s World includes tips on ways to work herbs into your daily life and your magical routine. Over 150 common herbs are covered, which for most witches includes all that will ever be needed. Most of the herbs are easily obtained, although one important herb – mandrake – is hard to find in the United States. (Occult stores will try to sell you mayapple as “American Mandrake” instead.) The entries for each herb are fairly short, but contain a brief description of the plant or its growing habitat, which I believe is important because most beginning witches first encounter these herbs in a package.I think what I like most about this book is that it doesn’t indulge in a plethora of correspondences. The tendency to go overboard with correspondences, to the point where it begins to inhibit learning rather than adding to it, is the bane of beginners – yet correspondences do have an important, necessary role in herb magic. I think this book sets the right balance to a thorny issue.If you already work a good deal with magical herbs, to the point where you have begun growing your own, this book is probably not for you, and if you decide to make this your area of expertise you will outgrow this book in a few years. This is not an encyclopedia, and I think we’ve come to expect the encyclopedic approach to herbs, whether for magic or healing. If you would like to use magical herbs a bit more than you do at present, this would be a good resource to have.A Kitchen Witch’s World of Magical Plants and Herbs is due out this fall and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.

Puleew Highway

August 1, 2014

The Old Sow (part 3)

July 25, 2014 The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/

The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/