Several years ago a North Country man shot and killed a member of his hunting party, the girlfriend of his son. This is an all too frequent tragedy, not worth a mention anywhere but the local news. The man said he thought the girlfriend was a deer, which is also not so unusual. More perplexing is that the woman was standing not far away from the shooter and was immobile, leaning against a tree. Regardless, the victim’s family and the prosecutor believed this was an accident, and the shooter was offered a reduced prison sentence that left some observers looking askance. Was it plausible that a sober man with good eyesight could accidentally shoot a person at close range, no matter how crazed he was to “get his buck”?

Or, could the victim-hunter – thinking about the deer, struggling to perceive the deer, trying to get in the mind of the deer, willing the deer to come closer – actually have turned into a deer? This alternative may seem more fantastic than the first, yet I have seen women (always women for some reason) momentarily turn into deer.

Moreover, I once received validation of sorts for my perception, during a women’s ritual. I glanced over to the woman beside me and saw that she had turned into a deer, and I thought I must be mistaken. This woman was very infatuated with bears, and I would never have associated her with deer. She was not fazed by this, however, explaining that her Cherokee great-grandmother had believed her to be attuned with the deer and had lobbied unsuccessfully to give her a deer name.

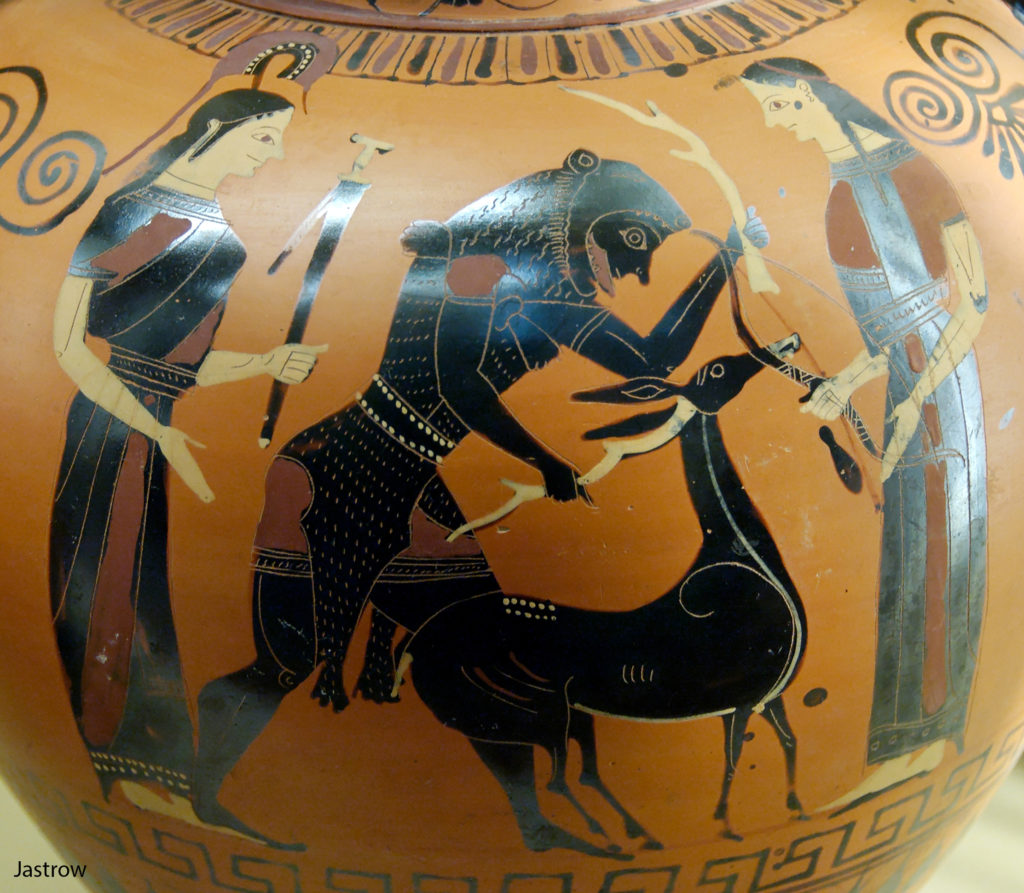

In the story of Sadb and Oisin the Irish heroine Sadb is turned into a fawn by one of her father’s enemies. She evidently retains the power to change back and forth, because she becomes the lover of the hero Fionn Mac Cumhaill after he spares her cervid form during a hunting expedition. The enraged druid changes her back into a doe, this time permanently, and in this form she gives birth to their son Oisin. The child appears human in all ways, save for a fawnlike forelock of hair, yet he can run as fast as a deer. (A slightly different version of this story appears in my book Invoking Animal Magic.)

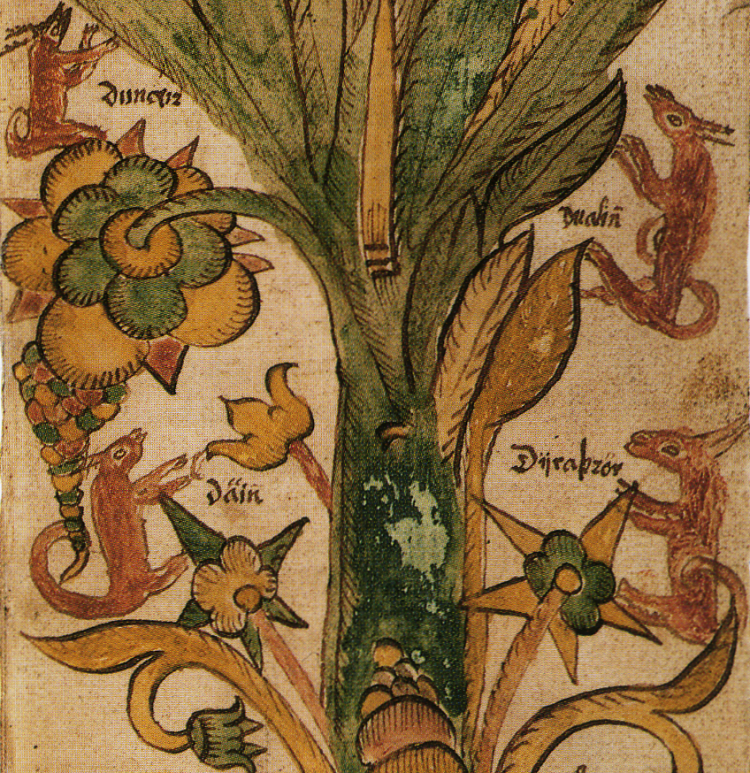

The Scottish hag Beinne Bhric changes into a gray deer, echoing legends of the Cailleach Bheur, the giant crone who keeps a herd of magic deer. The generic Scottish word for a shape-shifting charm, fith-fath (fee faw), literally means to take the shape of a deer.

Make no mistake: women can take the shape of deer, at least some women can. It is the stuff of legend, but nonetheless true. Serious inquiry has not been made into the qualities of the children of doe-mothers, but perhaps this is how shape-shifting ability is passed on. If you think you might be part deer, make your way carefully in the woods.

Sources:

Celtic Mythology. New Lanark, Scotland: Geddes and Grosset, 1999.

Matthews, Caitlin and John. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Wisdom: The Celtic Shaman’s Sourcebook. Shaftsbury, UK: Element Books, 1994.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.