So inevitable was the development of vision among motile creatures that it has developed along two different evolutionary pathways: the brain in vertebrates and the epidermis in invertebrates. That’s right, the skin. Among the more primitive jellyfishes, the eyes are raised patches of cells, called eyespots. These eyes cannot form images but can detect the direction light is coming from. The surface of the entire jellyfish appears to be photosensitive, sensing light even when the eyespots are covered.

SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.PostscriptIn the course of my research I discovered that “Jellyfish Eyes” is the name of a 2013 film by Takashi Murakami currently being screened at indie art theatres around the USA. I chose the title of this post before realizing this, as I was truly interested in actual jellyfish eyes. I may be the first to point out that the eyes on these “jellyfish” creatures are in no way anatomically correct. Alas, few sci-fi artists care about such things. Here is the trailer.

Tag: vision

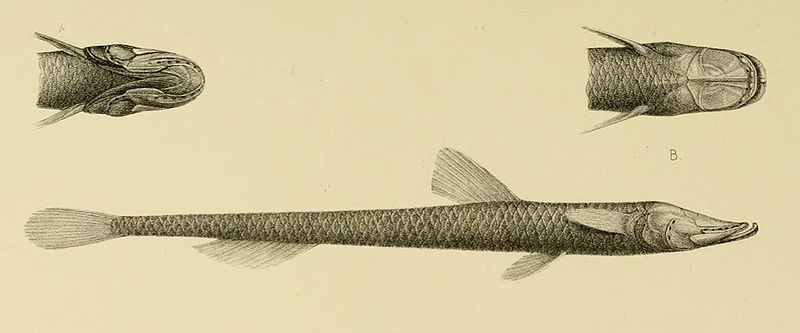

Ipnops

April 25, 2014

http://media.eol.org/content/2009/05/19/16/68617_orig.jpg (Photo R. B. Reyes) Ipnops Agassizii

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Ipnops.JPG/640px-Ipnops.JPG Ipnops Murrayi

Human and Animal Vision

April 18, 2014 It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

Ability to detect light (this is the core function of vision)Ability to locate the source of diffuse light (polarization)Ability to see in low lightAbility to see in bright lightSensitivity to changes in contrastAbility to see colorsRange of color visionAbility to distinguish hues within a narrow band of colorDepth perceptionDetection of movementAbility to see stationary objectsField of vision (including ability to see up and down as well as on a 360 degree plane)Focusing ability (including speed of focus on near and far objects)Ability to detect images at great distancesClarity of vision at far and close range (accommodation)Ability to detect shapes, both solid and outlineAbility to recognize patternsRapidity of image formation (analogous to frames per second in a camera)Clarity of underwater visionAbility to detect images below the surface of the water from above (and vice versa)Ability to compensate for idiosyncrasies in refraction (closely related to the factor above)Ability to compensate for movement (self locomotion as well as movement in the environment)Formation of a single image versus split visionCapacity for visual organs to withstand environmental challenges such as cold, pressure, and debris

I have not been able to find information comparing abilities to see and interpret auras.  So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

How Animals See

April 11, 2014 Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

Seeing More Clearly

September 20, 2013

Relearning to See

September 6, 2013 This isn’t so much a review of Thomas R. Quakenbush’s book Relearning to See, considered one of the best books explaining what is called the “Bates Method,” as it is an exploration of how the principles of natural vision have changed my thinking and my life. Although most people will elect to go the route of glasses and surgery to correct vision problems, and a few lucky people have perfect vision without considering the issue, I think these insights have implications beyond correcting eyesight, implications especially for the magical practitioner.I first decided to use natural vision methods over twenty-five years ago, when I was at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. I was camping out at the festival with several thousand women, and I rolled over my glasses in the tent while I was asleep, breaking them beyond repair. I was a day’s drive away from home, and my girlfriend did not know how to drive, so I had no idea how we would be able to get home. I was in a bit of a panic. In the end, some women scrounged up materials and pieced the glasses together so that they could stay on my nose long enough for the drive – but that was the turning point. I saw that my life was hanging by a thread, depending on these implements to interface with the world, and I vowed that I would find a way to emancipate myself from the tyranny of eyeglasses. I had never heard of “natural vision,” and I didn’t know anyone who had successfully thrown away their glasses, but I was determined to be free.Looking back, I can see that it was no coincidence that my commitment to better vision began here, just as it was no coincidence that my vision problems started in my first year of college. That year I began complaining of headaches, and my mother made an appointment for me at the “Vision Clinic,” as it was misnamed. It should have been called the “Adjusts to Poor Vision Clinic.” Sure enough, my eyesight had deteriorated. The explanation given was that I was spending long hours hunched over books, often under the glaring light of the library, and this was putting a strain on my eyes. I don’t dispute this explanation, and William H. Bates himself says that eyestrain is a big culprit in poor vision, but this is a surface explanation, like saying your car got dented because something hit it. What happened?College is a period of indoctrination as much as a period of learning. The biases, prejudices and imperatives of Western civilization bombard the young mind, as the institution struggles against itself to teach that mind how to think while dictating to it what to think. Especially for a woman, the incongruities are fierce. I took what amounted to a minor in English literature, and in all those classes read exactly one book written by a woman. The thing that bothers me most about that is that I didn’t “see” it. I majored in economics, and it was never mentioned that most wealth is in the hands of men and poverty disproportionately affects women. What bothers me now is that I didn’t “see” it. For a woman higher education is a period of great strain, one she survives by turning a blind eye, or at least a myopic one, to what is going on.Since I had not been inured to wearing glasses at a young age, of course I hated them, and I only wore them when reading a textbook – something that should have been instructive. When I graduated from college and began working for a large corporation, I began needing higher prescription lenses to read it all, and eventually needed glasses even to drive.Michigan provoked the turn around. This was in the earlier days of the festival, before the rise of organized attacks that changed the timbre of the music. I had to never been in a crowd of so many women. I had to never been in a large public gathering where men were completely absent. I realized with a shock that for many years, perhaps most of my life, I had lived in heightened alert against the threat of rape, both in and outside of my house. I had never reflected on this, never even noticed it, but the absence was startling. My body was conditioned to tighten at the sound of a low voice or a rustle of leaves – but then I would remember, “I am safe here.” This is what the early days of Michigan were like.It was also at Michigan that I met my first witch, or at least the first witch who would talk to me. I had imposed myself once on a woman who was pointed out to me at a local coffee house, who admitted to being a witch. I asked her where I could learn how to fly on a broom, and she brushed me off. But at Michigan there were lots of witches. I took a tarot class taught by Daughters of the Moon designer Fiona Morgan. I remember nothing about the class except that I felt excited to catch a glimpse of some thing totally new. Something was shifting in me. Looking back I see that my fuzzy eyesight was the distortions of patriarchy and my eyeglasses were the coping mechanism that allowed me to function. I left Michigan determined not to throw away my coping mechanism, but to dispense with the need for it altogether. The clearer vision that ensued allowed me to penetrate the occult realms.As often happens when I write a blog post, I have discovered that I have more to say than I thought I did. I will continue the topic of acquiring clear vision in another post.

This isn’t so much a review of Thomas R. Quakenbush’s book Relearning to See, considered one of the best books explaining what is called the “Bates Method,” as it is an exploration of how the principles of natural vision have changed my thinking and my life. Although most people will elect to go the route of glasses and surgery to correct vision problems, and a few lucky people have perfect vision without considering the issue, I think these insights have implications beyond correcting eyesight, implications especially for the magical practitioner.I first decided to use natural vision methods over twenty-five years ago, when I was at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. I was camping out at the festival with several thousand women, and I rolled over my glasses in the tent while I was asleep, breaking them beyond repair. I was a day’s drive away from home, and my girlfriend did not know how to drive, so I had no idea how we would be able to get home. I was in a bit of a panic. In the end, some women scrounged up materials and pieced the glasses together so that they could stay on my nose long enough for the drive – but that was the turning point. I saw that my life was hanging by a thread, depending on these implements to interface with the world, and I vowed that I would find a way to emancipate myself from the tyranny of eyeglasses. I had never heard of “natural vision,” and I didn’t know anyone who had successfully thrown away their glasses, but I was determined to be free.Looking back, I can see that it was no coincidence that my commitment to better vision began here, just as it was no coincidence that my vision problems started in my first year of college. That year I began complaining of headaches, and my mother made an appointment for me at the “Vision Clinic,” as it was misnamed. It should have been called the “Adjusts to Poor Vision Clinic.” Sure enough, my eyesight had deteriorated. The explanation given was that I was spending long hours hunched over books, often under the glaring light of the library, and this was putting a strain on my eyes. I don’t dispute this explanation, and William H. Bates himself says that eyestrain is a big culprit in poor vision, but this is a surface explanation, like saying your car got dented because something hit it. What happened?College is a period of indoctrination as much as a period of learning. The biases, prejudices and imperatives of Western civilization bombard the young mind, as the institution struggles against itself to teach that mind how to think while dictating to it what to think. Especially for a woman, the incongruities are fierce. I took what amounted to a minor in English literature, and in all those classes read exactly one book written by a woman. The thing that bothers me most about that is that I didn’t “see” it. I majored in economics, and it was never mentioned that most wealth is in the hands of men and poverty disproportionately affects women. What bothers me now is that I didn’t “see” it. For a woman higher education is a period of great strain, one she survives by turning a blind eye, or at least a myopic one, to what is going on.Since I had not been inured to wearing glasses at a young age, of course I hated them, and I only wore them when reading a textbook – something that should have been instructive. When I graduated from college and began working for a large corporation, I began needing higher prescription lenses to read it all, and eventually needed glasses even to drive.Michigan provoked the turn around. This was in the earlier days of the festival, before the rise of organized attacks that changed the timbre of the music. I had to never been in a crowd of so many women. I had to never been in a large public gathering where men were completely absent. I realized with a shock that for many years, perhaps most of my life, I had lived in heightened alert against the threat of rape, both in and outside of my house. I had never reflected on this, never even noticed it, but the absence was startling. My body was conditioned to tighten at the sound of a low voice or a rustle of leaves – but then I would remember, “I am safe here.” This is what the early days of Michigan were like.It was also at Michigan that I met my first witch, or at least the first witch who would talk to me. I had imposed myself once on a woman who was pointed out to me at a local coffee house, who admitted to being a witch. I asked her where I could learn how to fly on a broom, and she brushed me off. But at Michigan there were lots of witches. I took a tarot class taught by Daughters of the Moon designer Fiona Morgan. I remember nothing about the class except that I felt excited to catch a glimpse of some thing totally new. Something was shifting in me. Looking back I see that my fuzzy eyesight was the distortions of patriarchy and my eyeglasses were the coping mechanism that allowed me to function. I left Michigan determined not to throw away my coping mechanism, but to dispense with the need for it altogether. The clearer vision that ensued allowed me to penetrate the occult realms.As often happens when I write a blog post, I have discovered that I have more to say than I thought I did. I will continue the topic of acquiring clear vision in another post.