I was reading Iphigenia in Aulis this week, and another thought struck me about this myth.

The Greeks performed a ritual to Artemis prior to attacking Troy, offering Agamemnon’s daughter Iphigenia to her priestesshood, in order to secure favorable winds and other blessings from the goddess, who was venerated along the coast of Asia Minor. Buttering up the gods of the people you planned to attack, trying to get them to move over to your side, was an ancient war strategy. The story goes that Iphigenia was going to be killed at the altar, but by a miracle Artemis substituted a deer (or sometimes, a bear) at the last minute. This made a better story, but it (probably) was an embellishment. Maybe as part of the ritual to Artemis a deer was sacrificed. Maybe Iphigenia initially protested being relegated into chastity. Her mother almost certainly wasn’t onboard with the plan. But I’m not going along with the miracle substitution.

I was thinking this week about how Judy Grahn and other feminists have viewed the Trojan War as a last stand against Western patriarchy, the defeated Trojans representing the matriarchy. The all-women priestesshoods were relics from the matriarchies, their continuation an uneasy truce, or even a condition of surrender. As patriarchy gained a firmer hold, the Witch hunts of the Catholic (later Protestant) church sought to eliminate these relics of female power. The persecution of Dianics by American Witches are a continuation of that quest to subdue female power under male domination. Thinking of the autonomous priestesshood as a term of surrender puts the attacks on Dianics within Paganism in sharper focus. The three major methods of maintaining female subordination under Patriarchy are violence, economic oppression, and religion. Destruction of religious self-determination for women is an essential part of patriarchal control on the left and the right.

I tell the story of Iphigenia in my book, Invoking Animal Magic: A guide for the pagan priestess.

A Priestess for Artemis

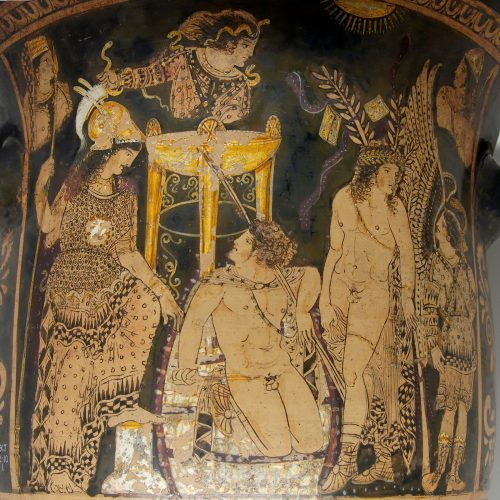

Iphigenia means “mother of strong children” and is probably an early name for Artemis or another bear goddess who became merged with Artemis. It later became an honorary title for her priestess. There are conflicting versions to the following story, but this much is not in dispute: The hero Agamemnon, leading an offensive against Troy, made little headway with his fleet due to unfavorable winds sent by Artemis, whom Agamemnon had offended. After consulting an oracle, Agamemnon offered Artemis his eldest daughter Iphigenia, thus earning the implacable wrath of his wife, Clytemnestra.

King Agamemnon of Mycenae was on the wrong side of Artemis from the start. His father had failed to honor a vow that he would sacrifice a prized lamb to the Huntress, and there is no record that the son felt an obligation to make good the pledge. Agamemnon, so capable in manly pursuits, once slew a white stag with a single arrow and boasted that Artemis could do no better. So true this boast: the beast was a member of the Virgin’s chariot team, and she would never have slain it.

When Queen Helen ran away with the Trojan prince Paris, Agamemnon took command of the retaliatory mission. Here was a chance to lead a great coalition and gain heroic stature. So much more the pleasure of Artemis, whose sympathies were inclined toward the Trojans, in thwarting Agamemnon’s plans. As the fleet readied to embark, an unfavorable northeast wind stranded them in the harbor of Aulis for weeks. Some say the goddess was miffed over the killing of a hare and cursed the whole expedition. Impatient to sail and bewildered by the persistent bad wind, Agamemnon called for an oracle. A chicken was gutted and the seer declared Artemis must be coaxed with a sacrifice of Agamemnon’s oldest daughter.

At first Agamemnon demurred. His wife would never surrender the girl, he protested. The military cohorts devised a scheme: send a messenger to the mother explaining that the demigod and prince Achilles wished to marry the princess, and she must come at once.

Clytemnestra, whose ambitions were wholly channeled in securing an advantageous match for her beautiful daughter, hastened to Aulis with Iphigenia, where a comedy of errors—or perhaps a tragedy of errors—awaited them. Agamemnon’s secret letter to Clytemnestra exposing the ruse had been intercepted, and the strong-willed matron arrived against her husband’s expectations demanding a marriage contract. Achilles, innocent and uninformed of the subterfuge (and married to someone else besides), was protesting there had been a mistake. Priests were completing preparations for Iphigenia’s dedication. The bamboozled daughter was balking at the plan, and her mother began begging Agamemnon and then threatening him. Surely there was a face-saving way out of the mess, by declaring Achilles an unknowing partner to deception if nothing else, but the fact remained that ships were stuck in harbor and men were itching for war.

Iphigenia, realizing her father’s ambitions and her country’s future revolved around her, finally stepped forward and declared she would go to Artemis. Iphigenia was as loyal, devoted and obedient as she was beautiful. Or maybe filial duty and patriotism were just a piece of it, and Artemis herself seduced the girl. Perhaps Artemis promised her adventure in a far flung country. She could be mistress of a great temple. The possessions of rich ladies who died in childbirth were sent to this temple, and Iphigenia’s beauty could be displayed against the finest fabrics and jewels.

Iphigenia’s acquiescence stirred a whirlwind. At the altar of Artemis the priests raised their knives to slit the girl’s throat, but at the last moment a bear cub was switched in her stead, and Iphigenia was swept on a red cloud to the land of Tauris. The same wind that whisked the new priestess filled the sails of the Greek fleet, and they were off to conquer Troy.

In offering Artemis the coveted maiden, Agamemnon was given the favorable wind he requested, but the act never improved the disposition of the goddess toward him. Later she abandoned him to the wrath of Clytemnestra.

It would be inaccurate to say the sacrifice of Iphigenia turned Clytemnestra away from her husband, for he had earned her hatred long ago. There comes a point, however, where dislike becomes disloyalty, and the proud mother had envisioned a greater future for her daughter than being exiled in a remote temple wearing dead women’s clothes. That the victorious Agamemnon returned from the war to be trapped in his wife’s net should surprise no one.

Iphigenia did not learn of her father’s fate for many years, until her brother Orestes was cast ashore at her temple under mysterious circumstances. As high priestess, Iphigenia presided over the slaying of refugees at the altar of Artemis, and during the pre-ceremonial interview learned of his identity.

What was Orestes doing in Tauris? Orestes admitted he was running from the horror of his actions. He had killed Clytemnestra, with Apollo’s approval, to avenge her murder of their father. After the filthy deed, Orestes was called to account before the Olympians, where Apollo spoke in his defense. The gods quarreled over his fate along political lines until the goddess Athena cast a vote with Apollo, tipping the verdict in Orestes’ favor.

An acquittal won through a brilliant defender and a stacked jury does not automatically erase the pangs of conscience, however, and Orestes had committed a horrendous deed. The Furies, sister deities who rule the conscience, tormented him for his crime until, driven to the edges of insanity, he consulted an oracle for a remedy. The oracle instructed him to steal the sacred statue of Artemis at Tauris and carry it to Brauron, where he was to build a new temple to the goddess. If he was unable to carry out this feat, Orestes declared, he might at as well die in Tauris; he could not go on living with this torment.

Surprisingly, Iphigenia decided to help her brother. She had grown tired of her exile and longed for the customs, faces and clothing styles of her native country. She told the Taurian king that Orestes and his companion were polluted by matricide and must be cleansed before sacrifice. That much was true; Orestes was not fit to have his throat slit on the altar of Artemis. She further told the leaders of her host country that she was borrowing the statue of the goddess for the purification rites. Iphigenia was certainly the double-crossing daughter of Agamemnon

Miraculously, with much adventure and intercession of the gods, the brother and sister eventually reached the ancient shrine in Brauron. A new temple was built, with the sacred image installed therein, and Iphigenia was named high priestess of the complex.

The presence of an important temple to Artemis so close to the city was an honor that made the Athenians nervous, as the wrath of Artemis had already sparked so many misadventures. Every family that could spare a daughter for a year sent the girl to Brauron to attend the goddess and learn the Brauronia ritual. The girls were called little bears and charmed the goddess with their dances. In this way, Artemis extended her healing side to Athens, protecting against plagues and enhancing the survival of infants and their mothers.