Category: Animals

Song of Khepri

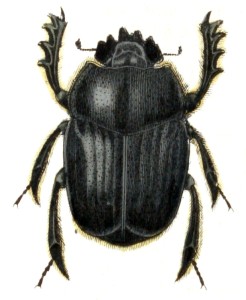

May 30, 2014 In the beginning the beginning beganIn the becoming the becoming becameI have come into being in the coming of my beingas I came into being in beginning timeTo the ancient Egyptians, the animating force Khepri was best exemplified by the scarab, also known as the Dung Beetle. This little critter descends on the scat of herbivores in droves to consume undigested nutrients. To consume a meal in peace, the scarab pats a piece of dung into a ball and rolls the scat some distance away, sometimes hiding the trophy in an underground niche. The Dung Beetle lays her eggs in concealed dung balls, which the larvae subsist on. The young adult emerges from the dung ball seemingly self-created.By pushing his large dung ball over the sand the scarab illustrated to the Egyptians the force pushing the sun across the sky in the daytime, then pushing the sun under the earth through the night. The scarab was not merely a symbol of this force, named Khepri, but an incarnation of a pervasive presence which manifested through this insect in a pure form.

In the beginning the beginning beganIn the becoming the becoming becameI have come into being in the coming of my beingas I came into being in beginning timeTo the ancient Egyptians, the animating force Khepri was best exemplified by the scarab, also known as the Dung Beetle. This little critter descends on the scat of herbivores in droves to consume undigested nutrients. To consume a meal in peace, the scarab pats a piece of dung into a ball and rolls the scat some distance away, sometimes hiding the trophy in an underground niche. The Dung Beetle lays her eggs in concealed dung balls, which the larvae subsist on. The young adult emerges from the dung ball seemingly self-created.By pushing his large dung ball over the sand the scarab illustrated to the Egyptians the force pushing the sun across the sky in the daytime, then pushing the sun under the earth through the night. The scarab was not merely a symbol of this force, named Khepri, but an incarnation of a pervasive presence which manifested through this insect in a pure form.

Kheper-i kheper kheperu kheper-kuy n kheperu m khepra kheperu m sep tepy.

I first heard this in 1987 at the Isis Oasis in Geyserville, California and it has always stayed with me. More information can be found in a book called Eternal Egypt: Ancient Rituals for a Modern World by Richard J. Reidy and at the website for a group called House of Keperu.

Blue Jay Communique

May 16, 2014

Jumping Spiders and Jellyfish Eyes

May 9, 2014So inevitable was the development of vision among motile creatures that it has developed along two different evolutionary pathways: the brain in vertebrates and the epidermis in invertebrates. That’s right, the skin. Among the more primitive jellyfishes, the eyes are raised patches of cells, called eyespots. These eyes cannot form images but can detect the direction light is coming from. The surface of the entire jellyfish appears to be photosensitive, sensing light even when the eyespots are covered.

SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.PostscriptIn the course of my research I discovered that “Jellyfish Eyes” is the name of a 2013 film by Takashi Murakami currently being screened at indie art theatres around the USA. I chose the title of this post before realizing this, as I was truly interested in actual jellyfish eyes. I may be the first to point out that the eyes on these “jellyfish” creatures are in no way anatomically correct. Alas, few sci-fi artists care about such things. Here is the trailer.

Ianuaria, Celtic Goddess of Music

May 2, 2014

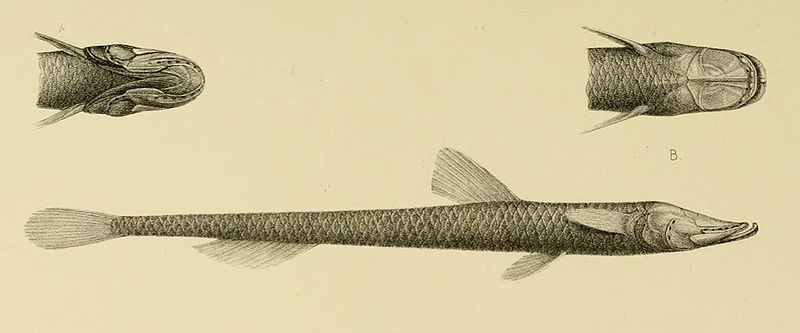

Ipnops

April 25, 2014

http://media.eol.org/content/2009/05/19/16/68617_orig.jpg (Photo R. B. Reyes) Ipnops Agassizii

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Ipnops.JPG/640px-Ipnops.JPG Ipnops Murrayi

Human and Animal Vision

April 18, 2014 It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

Ability to detect light (this is the core function of vision)Ability to locate the source of diffuse light (polarization)Ability to see in low lightAbility to see in bright lightSensitivity to changes in contrastAbility to see colorsRange of color visionAbility to distinguish hues within a narrow band of colorDepth perceptionDetection of movementAbility to see stationary objectsField of vision (including ability to see up and down as well as on a 360 degree plane)Focusing ability (including speed of focus on near and far objects)Ability to detect images at great distancesClarity of vision at far and close range (accommodation)Ability to detect shapes, both solid and outlineAbility to recognize patternsRapidity of image formation (analogous to frames per second in a camera)Clarity of underwater visionAbility to detect images below the surface of the water from above (and vice versa)Ability to compensate for idiosyncrasies in refraction (closely related to the factor above)Ability to compensate for movement (self locomotion as well as movement in the environment)Formation of a single image versus split visionCapacity for visual organs to withstand environmental challenges such as cold, pressure, and debris

I have not been able to find information comparing abilities to see and interpret auras.  So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

How Animals See

April 11, 2014 Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

Eagle and Ratatosk

February 28, 2014More to come in a few weeks on cuisine in Mesopotamia: food and the dead, feasting with the gods and a few other topics. A diversion this week for something too wonderful to pass up.

I don’t know if people remember the essay I wrote on Ratatosk, the Red Scoundrel for Return to Mago blog. In Germanic lore Ratatosk scampers up and down the world tree carrying insults between Nidhogg, the serpent-dragon who nibbles the roots of the tree, and a giant eagle (unnamed as far as we know) who lives in the top branches. Anyway, I found a photo of it! This really is happening, still.

Another Review For “Invoking Animal Magic”

February 24, 2014 This review, from Before It’s News, a UK publication, was published last August, but I just recently ran across it. Obviously, I didn’t learn about it until long after it was news.Invoking Animal Magic can be purchased in bookstores or on Amazon here.

This review, from Before It’s News, a UK publication, was published last August, but I just recently ran across it. Obviously, I didn’t learn about it until long after it was news.Invoking Animal Magic can be purchased in bookstores or on Amazon here.