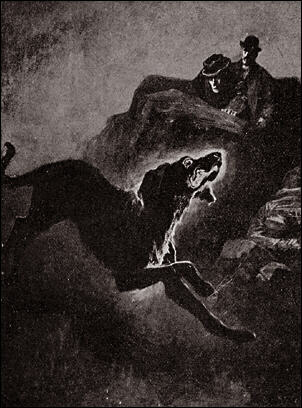

Several people had seen a creature upon the moor which corresponds with this Baskerville demon, and which could not possibly be any animal known to science. They all agreed that it was a huge creature, luminous, ghastly, and spectral. I have cross-examined these men, one of them a hard-headed countryman, one a farrier, and one a moorland farmer, who all tell the same story of this dreadful apparition, exactly corresponding to the hell-hound of the legend.

The creator of Sherlock Holmes had a vivid imagination that his famous protagonist would have sneered at. Conan Doyle’s impressionable mind was piqued by a story he chanced upon in 1901 when driven from the golf course by a storm. His companion regaled him with tales of a phantom dog that haunted the countryside, with bloody eyes and a luminous aura. Throw in a family curse, an evil aristocrat, and a lovely victim, and the legend had all the ingredients of a first rate mystery. The Hound of the Baskervilles is considered Conan Doyle’s most expertly crafted plot and one of the best detective novels ever penned.

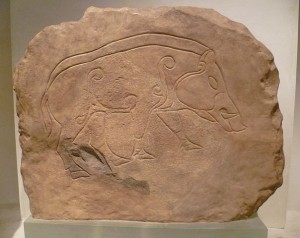

But this was not an obscure folktale, at least not the hellhound part of it. Legends of a phantom dog from the death realm, usually huge and black, are found wherever there has been Celtic influence, most notably the British Isles but also France, Germany, and Spain. Black Dog anecdotes have even cropped up in North and South America, all containing elements of the core fable: a black dog inhabiting liminal spaces, strongly connected with death. Conan Doyle probably did not know that the Black Dog is also a storm dweller, making the eminent author’s retreat from the golf course that inclement day appear to have the paw prints of fate.

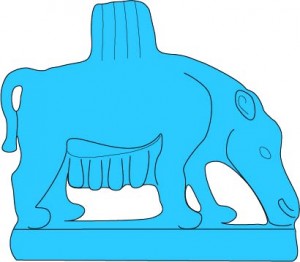

In this upcoming webinar we will examine the origin of the Black Dog as emissary of the Mother-goddess. We will also discuss myths originating in Mesoamerica and the Philippines that provide clues to the meaning of the strange and persistent tales of the phantom dog.

Befriending the Black Dog

Monday, December 8, 2014

7:00–8:00 pm Eastern Time (US)

Attend live or stream later

Cost $25 $10

Pre-registration required