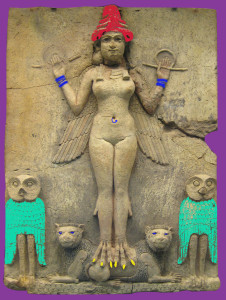

One of the things I appreciate greatly about Mesopotamian mythology is the humor. It’s not just the things that sound funny to us today, from far outside the culture, that tickle me. There are some of those, to be sure, as there are with any mythology. When Ishtar issues her zombie threat at the gates of hell, declaring she will raise up the dead to devour the living unless she is allowed to pass through, Americans giggle because we think zombies are hilarious. Mesopotamians were chuckling because when Ishtar issues this blackmail she has not yet been to hell (she’s trying to get in!) and has no power there. It is an empty threat. Also, even if the scenario she describes were something she would do (it isn’t), it’s a bit of overkill.

Sometimes we understand right away what the Mesopotamians were laughing at, such as when the god Enki gives Inanna all the accoutrements of civilization while he is in a drunken expansive mood, then gets an a dudgeon when he sobers up and realizes all his stuff is missing. Other times it takes some familiarity with ancient cultures to catch the humor. In the Gilgamesh myth the hero Enkidu takes the haunch of the bull he has just killed, to Ishtar’s outrage, and he throws it at the goddess. The haunch was considered the choicest part of the animal, and when a bull was sacrificed this was the part that was ritually offered to the deity. Here, instead of offering the haunch with humble obeisance, the hero is deliberately offending the goddess by throwing it at her. No doubt there are a lot of inside jokes in these stories that we don’t have the background to catch.

Sometimes the stories don’t convey humor so much as wry irony. This is the case with the story of how the fly came to pester humankind, or how Gilgamesh lost his herb of immortality.

I will be teaching an online class in another month where we well discuss these myths, particularly the one about Inanna’s descent into the underworld. Reading materials and instructions for joining the live sessions will be available April 26, and the first live session will be Sunday, May 3. Sessions will last for about an hour and meet every other week until July 26. The class will be taught through Mago Academy, and information for signing up can be found at this website.