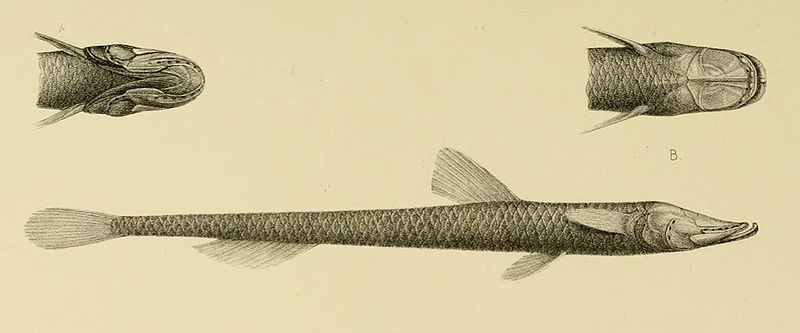

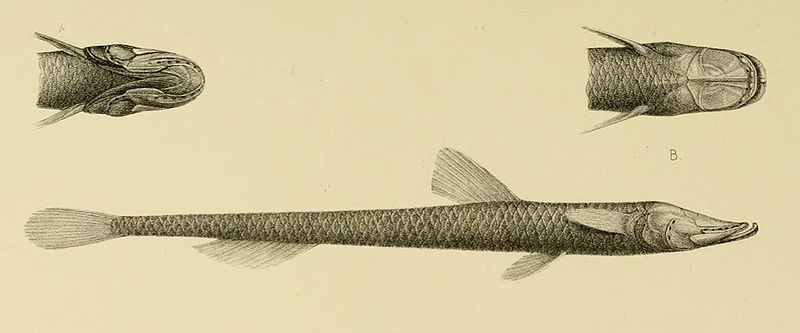

http://media.eol.org/content/2009/05/19/16/68617_orig.jpg (Photo R. B. Reyes) Ipnops Agassizii

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Ipnops.JPG/640px-Ipnops.JPG Ipnops Murrayi

http://media.eol.org/content/2009/05/19/16/68617_orig.jpg (Photo R. B. Reyes) Ipnops Agassizii

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Ipnops.JPG/640px-Ipnops.JPG Ipnops Murrayi

It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

It turns out that humans are highly anthropocentric in how we conceive of vision. The measures that we use tend to be areas where problems in human vision arise: focusing at distant and close range, seeing at night, depth perception, field of vision, and colorblindness. We don’t factor in things that most humans can do easily, such as recognize patterns, and we also don’t think about things we can’t do at all, such as recognize the source of diffuse light.Here is a list of factors that vision entails (which may not be complete):

Ability to detect light (this is the core function of vision)Ability to locate the source of diffuse light (polarization)Ability to see in low lightAbility to see in bright lightSensitivity to changes in contrastAbility to see colorsRange of color visionAbility to distinguish hues within a narrow band of colorDepth perceptionDetection of movementAbility to see stationary objectsField of vision (including ability to see up and down as well as on a 360 degree plane)Focusing ability (including speed of focus on near and far objects)Ability to detect images at great distancesClarity of vision at far and close range (accommodation)Ability to detect shapes, both solid and outlineAbility to recognize patternsRapidity of image formation (analogous to frames per second in a camera)Clarity of underwater visionAbility to detect images below the surface of the water from above (and vice versa)Ability to compensate for idiosyncrasies in refraction (closely related to the factor above)Ability to compensate for movement (self locomotion as well as movement in the environment)Formation of a single image versus split visionCapacity for visual organs to withstand environmental challenges such as cold, pressure, and debris

I have not been able to find information comparing abilities to see and interpret auras.  So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

So which animal has the best vision? I was a few chapters into this book before I realized what a silly question this is. Each animal has a type of vision perfectly adapted to its environmental niche. No eye or set of eyes can function in all areas extraordinarily well, because there are a few areas that are mutually exclusive and so it’s a choice between specialization or compromise. If I did have to pick the animal with the best vision, however, it would be any member of the ape family, including humans. No doubt many will not believe me and will dismiss this as more anthropocentricism. I say this because while there are animals who outperform us in every area of vision, except perhaps pattern recognition, our eyes function competently in a wide range of environments and circumstances. Our eyes do little that is spectacular but almost everything well. This is probably the main reason we have adapted to so many environments around the globe.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.Photo credits: Eagle–Vtornet; Chimpanzee–Thomas Lersch

Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

Most of us intuitively understand that other animals do not see the world the way we humans do, and we like to imagine how things look from their point of view. It turns out that the ways of seeing are more intricate and varied than we realize.I am returning this week to a favorite topic of mine: vision. Over the next several weeks I will be sharing insights gleaned from my perusal of an out-of-print book, How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World, by Sandra Sinclair. This book examines eyesight in a wide range of creatures, from insects to mammals, sea dwellers to migrating birds.I did not realize when I picked up this book how unique it is, really one-of-a-kind. Since it was published in 1985 the other books on the subject have been children’s books, which is par for the course. Books on the really interesting topics seem to be written for kids, not grownups. Lack of interest may not be the primary factor here, however. The subject matter is difficult, so much so that biologists and others who study in this area use words and concepts that most people have only a fuzzy understanding of. Sinclair spent years researching her material under the mentorship of Dr. Dean Yeager of The State University of New York College of Optometry, and Dr. Yaeger writes in his foreword that even he was forced to read outside his areas of expertise in order to assist with the project. This seems to be the kind of book that only a very bright journalist with generous assistance from experts could make comprehensible to the lay reader. Even so, I do not think I would have been able to understand this material had I not already read some basic books about human eyesight such as Relearning to See by Thomas Quackenbush, which I wrote about last year.I have tried unsuccessfully to find a more up to date version of Sinclair’s work. I have found only two books that are close: a 2012 book called How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision by Olga F. Lazareva et al and Animal Eyes by Michael F. Land and Dan-Eric Nilsson. The blurb at Goodreads boasts that How Animals See the World “…contains 26 chapters written by world-leading experts” and calls it “An exhaustive work in range and depth, … a valuable resource for advanced students and researchers in areas of cognitive psychology, perception and cognitive neuroscience, as well as researchers in the visual sciences.” Animal Eyes is billed by the publisher as “…a comparative account of all known types of eye in the animal kingdom, outlining their structure and function with an emphasis on the nature of the optical systems and the physical principles involved in image formation.” Both rather dense sounding texts assume a solid knowledge base in the visual sciences, which makes me appreciate Sinclair’s work all the more. I have to say, however, that I found even this book a stretch.Over the next few months, look forward to juicy bits of trivia about some very weird ways of seeing.SourceSinclair, Sandra. How Anmals See: Other Visions of Our World. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

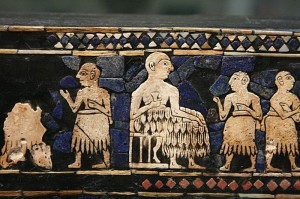

In writing this book I did not intend to provide an exhaustive, scholarly study of eating and drinking among our venerable ancestors from ancient Mesopotamia. Such a work would have been tedious and dry, addressed (at the expense of honest readers) only to academics, who scarcely need it and may not want it.

I am not an academic or a scholar, so I appreciate that attention was paid to making the study of Mesopotamian cuisine interesting. I have, however, read a fair amount about the Sumerians and Akkadians, more than the average Pagan, so I also have some general context in which to place this cornucopia of information about food. One thing that jelled for me in exploring this book, which had only vaguely registered before, was an appreciation for the enthusiasm with which the ancient Mesopotamians approached the business of life. This can be glimpsed in their descriptions of their games, in the homage paid in word and picture to lovemaking, and in the exuberance with which the hero Gilgamesh throws himself into adventure, friendship, and even sorrow. Yet it was only in studying the art and excess of their food and drink that I came to recognize the Mesopotamian commitment to enjoying life. This was not merely the hedonism of “eat, drink, and be merry,” although sensuality certainly played a part. Mesopotamians worked as hard as they played, and they took significant pride in their accomplishments. They also loved hard: they loved their cities, their craftsmanship, their civilization, and the gods who rewarded them so generously for their labors. Their joie de vivre was not tempered by cynicism, as it so often is today, although they had a fine appreciation for ironic humor. If in the ancient world the Egyptians strove to be memorable, the Israelites to be good, the Greeks to be wise, the Romans to be victorious, the Celts to be honorable, and the Germans to be brave, the Mesopotamians strove to extract the most satisfying enjoyment possible out of life.In closing let’s turn once again to the words of the tavern keeper, sometimes identified as the goddess Ninkasi, to Gilgamesh

Humans are born, they live, then they die,this is the order that the gods have decreed.But until the end comes, enjoy your life,spend it in happiness, not despair.Savor your food, make each of your daysa delight, bathe and anoint yourself,wear bright clothes that are sparkling clean,let music and dancing fill your house,love the child who holds you by the hand,and give your wife pleasure in your embrace.That is the best way for a man to live.

SourcesBottero, Jean. The Oldest Cuisine in the World: Cooking in Mesopotamia. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.Mitchell, Stephen. Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press, 2004.