The link to the webinar Mystick Path of the Deer has been corrected. Here it is again:

https://hearthmoonrising.com/webinar/

This webinar promises to answer many of your questions, including why I’m misspelling the word “mystick.”

The link to the webinar Mystick Path of the Deer has been corrected. Here it is again:

https://hearthmoonrising.com/webinar/

This webinar promises to answer many of your questions, including why I’m misspelling the word “mystick.”

Several years ago a North Country man shot and killed a member of his hunting party, the girlfriend of his son. This is an all too frequent tragedy, not worth a mention anywhere but the local news. The man said he thought the girlfriend was a deer, which is also not so unusual. More perplexing is that the woman was standing not far away from the shooter and was immobile, leaning against a tree. Regardless, the victim’s family and the prosecutor believed this was an accident, and the shooter was offered a reduced prison sentence that left some observers looking askance. Was it plausible that a sober man with good eyesight could accidentally shoot a person at close range, no matter how crazed he was to “get his buck”?

Or, could the victim-hunter – thinking about the deer, struggling to perceive the deer, trying to get in the mind of the deer, willing the deer to come closer – actually have turned into a deer? This alternative may seem more fantastic than the first, yet I have seen women (always women for some reason) momentarily turn into deer.

Moreover, I once received validation of sorts for my perception, during a women’s ritual. I glanced over to the woman beside me and saw that she had turned into a deer, and I thought I must be mistaken. This woman was very infatuated with bears, and I would never have associated her with deer. She was not fazed by this, however, explaining that her Cherokee great-grandmother had believed her to be attuned with the deer and had lobbied unsuccessfully to give her a deer name.

In the story of Sadb and Oisin the Irish heroine Sadb is turned into a fawn by one of her father’s enemies. She evidently retains the power to change back and forth, because she becomes the lover of the hero Fionn Mac Cumhaill after he spares her cervid form during a hunting expedition. The enraged druid changes her back into a doe, this time permanently, and in this form she gives birth to their son Oisin. The child appears human in all ways, save for a fawnlike forelock of hair, yet he can run as fast as a deer. (A slightly different version of this story appears in my book Invoking Animal Magic.)

The Scottish hag Beinne Bhric changes into a gray deer, echoing legends of the Cailleach Bheur, the giant crone who keeps a herd of magic deer. The generic Scottish word for a shape-shifting charm, fith-fath (fee faw), literally means to take the shape of a deer.

Make no mistake: women can take the shape of deer, at least some women can. It is the stuff of legend, but nonetheless true. Serious inquiry has not been made into the qualities of the children of doe-mothers, but perhaps this is how shape-shifting ability is passed on. If you think you might be part deer, make your way carefully in the woods.

Sources:

Celtic Mythology. New Lanark, Scotland: Geddes and Grosset, 1999.

Matthews, Caitlin and John. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Wisdom: The Celtic Shaman’s Sourcebook. Shaftsbury, UK: Element Books, 1994.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.

Learn more about deer magic in the upcoming webinar,

The Mystick Path of the Deer

Happy Solstice everyone! This Sunday-Monday marks the time when, from our perspective, the sun is at its southernmost arc on the horizon in the Northern Hemisphere or its northernmost arc in the Southern Hemisphere.

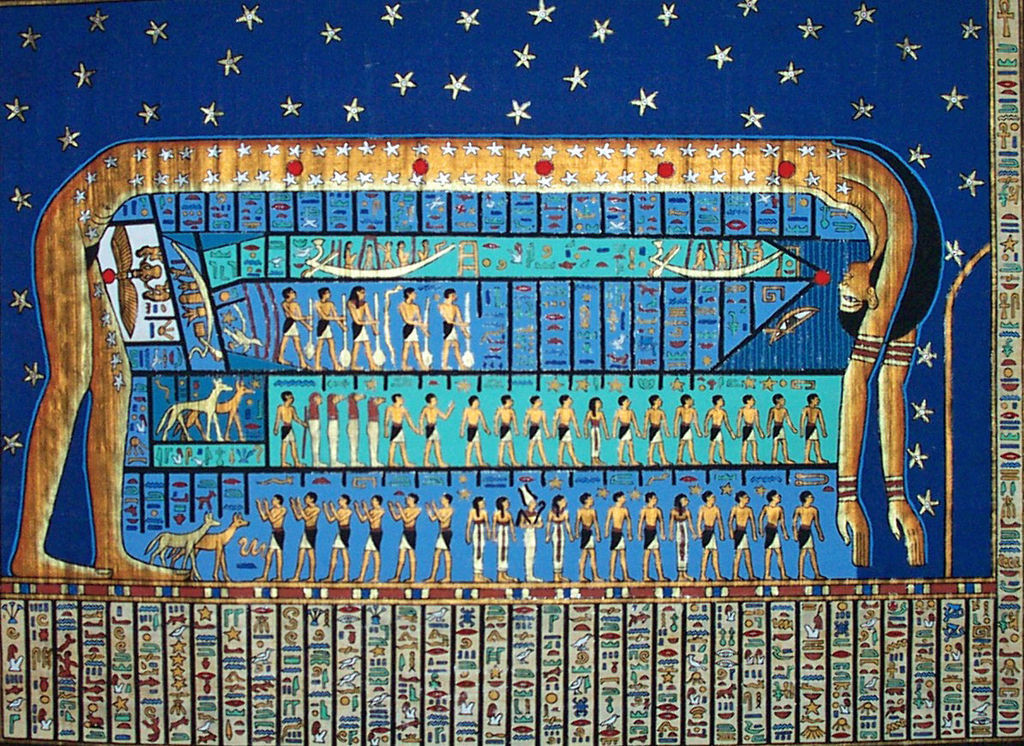

Barbara Lesko in The Great Goddesses of Egypt shares this interesting perspective on the Winter Solstice:

A professional astronomer has recently published maps of the pre-dawn Egyptian sky as it would have appeared in the predynastic period on the morning of the winter solstice. The Milky Way exhibits an amazing likeness to the outsretched figure of the goddess Nut, with her feet on one horizon and her hands touching the other. The sun would have appeared in the winter solstice in the correct area of the figure’s anatomy to suggest to observers that it was being born by Nut. Nine months earlier, at the spring quinox, the sun began to rise an hour and a quarter after sunset in such a position that it appeared to fall into Nut’s mouth, which would have easily suggested the idea that the great female in the sky was swallowing the sun, only to bear him nine months later during the last days of what is now December.

Could this explain why the birth of the Sun King is celebrated at this time?

Here is another scientific explanation of sun movements and weather patterns.

Few things are more exhilarating than running through the woods on a spongy trail and hitting your stride. I was moving in that effortless state of freedom on a late afternoon run when my partner pulled up suddenly and commanded me to stop. We were in a large open stand of pine with little undergrowth.

“Don’t move,” my partner whispered.

“I don’t see anything,” I replied.

“Shhh! Right in front of you,” he said – and then I saw it. A large doe a few feet away, standing perfectly immobile. She was relying on her coloring and her stillness for camouflage, and I would have passed close by her if I had not been alerted. Yet I am a fairly observant person. I can’t help but wonder if pine trees change into deer when they have a hankering for movement, or if deer swiftly turn to pine when they need to disappear.

Can you spot the spotted deer in the forest? It takes a willingness to move between worlds, and by acquiring this depth of perception you greatly enhance your psychic abilities. The upcoming webinar The Mystick Path of the Deer will focus on better understanding and attuning with this remarkable creature.

The Mystick Path of the Deer

Monday, January 12, 2015

7:00–8:00 pm Eastern Time

Attend live or stream later

Cost $25

Pre-registration required

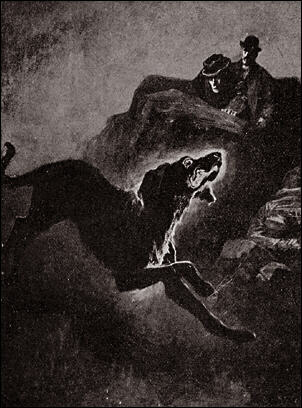

And if a man shall meet the black dog once, it shall be for joy; the second time, it shall be for sorrow; and the third time, he shall die.

The webinar on Monday December 8th will be about the phantom black dog, a phenomenon that stretches back into Pagan times yet remains surprisingly contemporary. One of the best known examples is the Black Dog of Hanging Hills, Connecticut. Geologist W.H.C. Pynchon relates how he and his colleague Herbert Marshall were exploring West Peak in the Hanging Hills range when they chanced upon the fabled Black Dog. Marshall, who had already encountered the Black Dog twice, scoffed at the legend; but later that day he slipped on a patch of ice and tumbled to his death.

Unlike the huge terrifying death hounds of the British Isles, the Black Dog of Hanging Hills is a small friendly scruffy character with a silent bark. He leaves no footprints. There are common sightings of this pup on West Peak and, more rarely, accidental hiking deaths in the area. The unusual rock formations and panoramic views make the peak an enticing destination for off trail exploration, yet the volcanic rock is brittle and the surfaces are littered with scree, making this a dangerous place for bushwhacking. No one has suggested that the Black Dog is anything but a messenger of impending danger or disaster. Hikers describe him as an engaging pup whose sole disconcerting quality, aside from the legends surrounding him, is a tendency to appear and disappear unexpectedly.

Pynchon declared himself a firm believer in the common wisdom surrounding the Black Dog of Hanging Hills, but sticklers for fact are quick to point out that, while Pynchon is on record as having encountered the Black Dog twice, he did not follow his friend some years later into a deadly ravine on West Peak. Pynchon died in 1910 on Long Island, and Herbert Marshall is the only known geologist to have a little black dog silently speak his doom.

Sources:

Pure, delicious rumor.

Befriending the Black Dog

A webinar with Hearth Moon Rising

Monday, December 8, 2014

7:00 – 8:00 Eastern Time

Attend live or stream later

Pre-registration required

Several people had seen a creature upon the moor which corresponds with this Baskerville demon, and which could not possibly be any animal known to science. They all agreed that it was a huge creature, luminous, ghastly, and spectral. I have cross-examined these men, one of them a hard-headed countryman, one a farrier, and one a moorland farmer, who all tell the same story of this dreadful apparition, exactly corresponding to the hell-hound of the legend.

The creator of Sherlock Holmes had a vivid imagination that his famous protagonist would have sneered at. Conan Doyle’s impressionable mind was piqued by a story he chanced upon in 1901 when driven from the golf course by a storm. His companion regaled him with tales of a phantom dog that haunted the countryside, with bloody eyes and a luminous aura. Throw in a family curse, an evil aristocrat, and a lovely victim, and the legend had all the ingredients of a first rate mystery. The Hound of the Baskervilles is considered Conan Doyle’s most expertly crafted plot and one of the best detective novels ever penned.

But this was not an obscure folktale, at least not the hellhound part of it. Legends of a phantom dog from the death realm, usually huge and black, are found wherever there has been Celtic influence, most notably the British Isles but also France, Germany, and Spain. Black Dog anecdotes have even cropped up in North and South America, all containing elements of the core fable: a black dog inhabiting liminal spaces, strongly connected with death. Conan Doyle probably did not know that the Black Dog is also a storm dweller, making the eminent author’s retreat from the golf course that inclement day appear to have the paw prints of fate.

In this upcoming webinar we will examine the origin of the Black Dog as emissary of the Mother-goddess. We will also discuss myths originating in Mesoamerica and the Philippines that provide clues to the meaning of the strange and persistent tales of the phantom dog.

Befriending the Black Dog

Monday, December 8, 2014

7:00–8:00 pm Eastern Time (US)

Attend live or stream later

Cost $25 $10

Pre-registration required

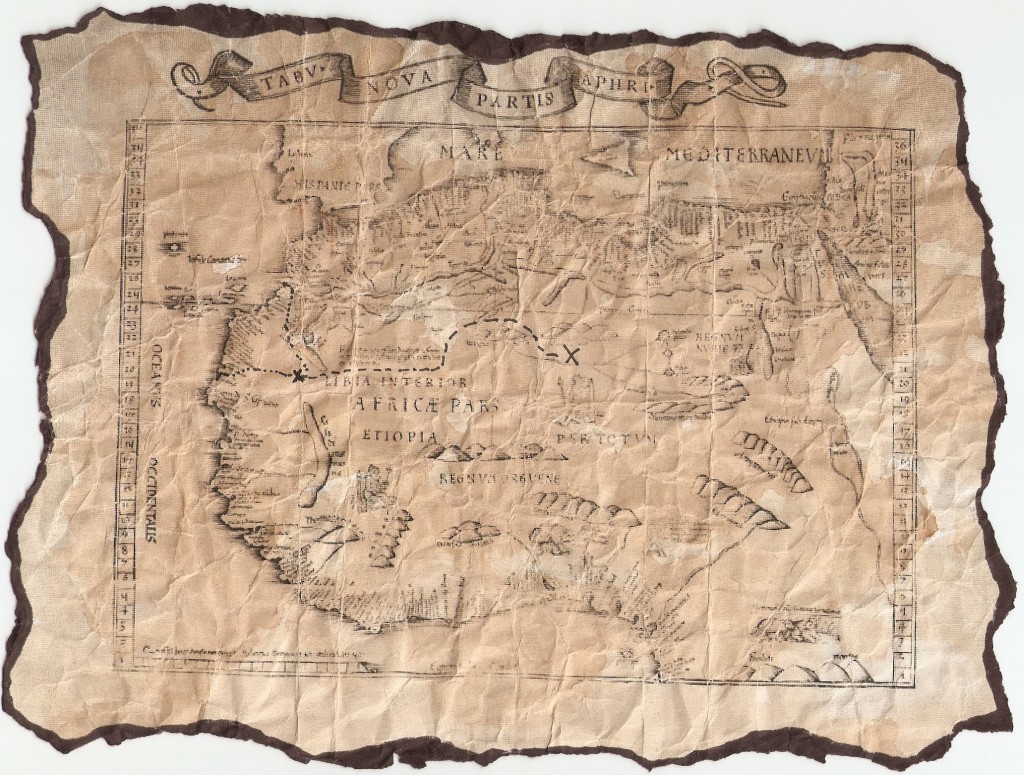

In magic we use symbols frequently: scrawled on a candle, a piece of paper, or even in dirt. The symbol X is a particularly versatile symbol that belongs in anyone’s bag of tricks.

I believe in general that a symbol, like a word, should have a clear definition, that it should mean something, but X is often the symbol for the unknown. In algebra, for example, it is used as the symbol for the unknown quantity and does not necessarily have a precise definition, which is not the same thing as saying it is undefined. It may be a real number, for instance, or a whole number, or a prime number less than 100. Likewise X in a magical equation can stand for a specific unknown – perhaps a manuscript that is sought whose title is unknown. In detective fiction, X often stands for an unknown person, either the person who commits the crime or some other enactor of an anonymous deed. You would not be using X in your magic to summon a criminal (at least I hope not), but X could stand for an unknown donor or other helper.

The X shaped rune gyfu means “A sign of hospitality and friendship, of joy and celebration.”* It may represent an offering to the gods or some other kind of gift. This interpretation of gyfu relates to another important intimation of the symbol X: as a mark on a map indicating the location of buried treasure. X can mean treasure or it can refer to the place that is sought, be it literal or metaphorical.

*D. Jason Cooper, Using the Runes. (Wellingborough, UK: The Aquarian Press), 1986.

The persecution of cats in Western Europe during the Witch Craze is widely known. Under Christian influence cats were considered agents of the devil or witches in disguise. The terrifying specter of the cat may have pre-Christian antecedents in Celtic countries however. The legend of “King Arthur and the Cat,” though recorded well into Christian times, may reveal something about earlier Celtic attitudes toward the cat, attitudes possibly influenced by interactions with the indigenous wildcat.

The story begins with a fisherman alone in his boat making a vow to offer the first fish he catches to the Lord. But the first catch is unusually fine, so the fisherman hedges and says he will donate the second fish. The second fish is even bigger than the first, so the third catch is then offered. The third fish, however, is not a fish at all, but a small black kitten. The fishermen has need of a mouse catcher, so this third catch does not go to the Lord but is taken to the man’s home.

The kitten grows into a giant cat who eventually strangles the fisherman and his family, then escapes into the countryside where he wreaks havoc, taking many lives. The populace lives in terror and the land becomes desolate.

Eventually Merlin intervenes and enlists the aid of King Arthur. It takes both Merlin’s magic and Arthur’s courage to vanquish the cat, who attacks so persistently that the feet of the dead cat remain fastened to Arthur’s shield.

This fourteenth century French tale has parallels in the eleventh century Irish Voyage of Mael Duin and the sixteenth century English short story Beware the Cat. In all of these stories there is a fierce, implacable cat who takes human life. The cat in these cases does not follow the witch hunter’s narrative as a devilish seducer of the innocent: he is an agent of retribution for a serious offense against Celtic morality. In King Arthur and the Cat the sin is a broken vow, in Beware the Cat it is a brutal raid, and in Voyage of Mael Duin it is a violation of hospitality. The savage cat is not an expression of evil, but of justice.

The webinar “Magical History of the Cat” has been rescheduled for Monday, November 24th, so there’s still time to register. Details are at the webinar website.

Sources

“An Irish Odyssey: The Voyage of Mael Duin” in Celtic Mythology. New Lanark, Scotland: Geddes and Grosset, 1999.

Baldwin, William. Beware the Cat.

“Wilde, Lady Francesca Speranza. “King Arthur and the Cat” in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland.