The heat of summer is full upon us, excruciating in parts of the Northern Hemisphere, and this makes me think of scorpions. It’s a reminiscence, not a vigilance, because I now live far enough north that I don’t have to check my shoes every time I put them on. No wonder people in Arizona like sandals!

Scorpions are fascinating, multi-faceted creatures. They embody mystery, in the sense that they become more intriguing the more you learn about their secret world. They embody boundaries, in the sense that much larger creatures are respectful of them and their venom. They embody transformation, in the sense that their venom has huge effects on the human body.

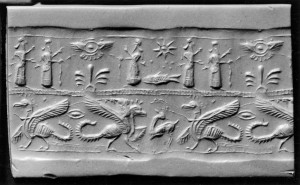

Scorpions are dangerous and live in a dangerous world, hunted continually by birds. Even mating is dangerous. Summer is scorpion courtship season, involving a dance pincer-to-pincer under the starry sky. That sounds sweet, but since both parties are heavily armed it can involve stinging. Some scorpions reproduce parthenogenetically, which seems like a better idea.

Here is an excerpt from a chapter on scorpions in Divining with Animal Guides:

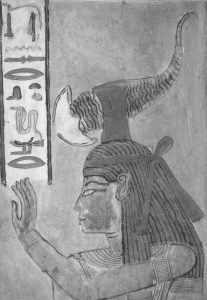

The Egyptians had a scorpion goddess, Selket, who was called upon for protection against—you guessed it—scorpions. Selket was one of the guardians of the “canopic jars,” the containers holding the pickled remains of four vital organs of the deceased: liver, intestines, lungs, and stomach. The heart, the all-important anchor of the soul within the body, was preserved, wrapped, and returned to the body cavity. The brain was thrown in the trash. Each of the four organs was guarded by a specific deity, and Selket protected the intestines. The guardian deity was depicted on the outside of the jar along with hieroglyphic prayers to invoke that deity’s protection. This label also helped the expired prince remember which jars housed his various organs. Labeling funerary objects was an important precaution: not only did the rich take a lot of stuff with them, the world beyond had so many people—as many people as had ever trod the earth—that mixups were a potential complication. Thus everything was tagged, and clothing and bedding contained laundry marks. This consistent attention to organizational detail in preparation for the final voyage may strike some people as absurd, but think about it: would you want to root around in someone else’s canopic jar by mistake? Selket was entrusted with an important responsibility.

Selket’s other major role was helping the deceased draw their first breath in the afterlife. Most “death goddesses” are really death-and-birth goddesses, and breath is the fundamental connection to life. Selket initiated breathing in both worlds. To emphasize this nurturing aspect of Selket’s character, she was sometimes depicted without a stinger or as a stingless Water Scorpion. The Water Scorpion is not an arachnid but an insect in a family biologists call the “true bugs.” Water Scorpions are true bugs and fake scorpions, and most of them don’t even faintly resemble scorpions, but there are a few with pincer-like front legs and long tails that look vaguely reminiscent. The “tail” is actually a breathing tube that sticks out of the shallow water. The Nile species depicted in art has a double-breasted air tube.

Here is an excerpt from a longer article on scorpions in the anthology, iPagan:

Renaissance scorpion magic was unequivocally combative, used surreptitiously for destroying personal enemies. Outside of hot climates a scorpion would have been a scarce commodity, all the more so because there was no use for the creature which enjoyed public approbation, and this must have heightened the allure for those dedicated to intrigue. Picture a man in tights with a ridiculously large shirt collar gazing down at a desiccated scorpion while rubbing his hands together and saying “Hahahahaha.”