Magical herbology is an area every witch needs to develop competency in, whatever her eventual area of focus. The challenge is to gain more than an abstract knowledge of herbs, to find opportunities for hands-on learning. A Kitchen Witch’s World includes tips on ways to work herbs into your daily life and your magical routine. Over 150 common herbs are covered, which for most witches includes all that will ever be needed. Most of the herbs are easily obtained, although one important herb – mandrake – is hard to find in the United States. (Occult stores will try to sell you mayapple as “American Mandrake” instead.) The entries for each herb are fairly short, but contain a brief description of the plant or its growing habitat, which I believe is important because most beginning witches first encounter these herbs in a package.I think what I like most about this book is that it doesn’t indulge in a plethora of correspondences. The tendency to go overboard with correspondences, to the point where it begins to inhibit learning rather than adding to it, is the bane of beginners – yet correspondences do have an important, necessary role in herb magic. I think this book sets the right balance to a thorny issue.If you already work a good deal with magical herbs, to the point where you have begun growing your own, this book is probably not for you, and if you decide to make this your area of expertise you will outgrow this book in a few years. This is not an encyclopedia, and I think we’ve come to expect the encyclopedic approach to herbs, whether for magic or healing. If you would like to use magical herbs a bit more than you do at present, this would be a good resource to have.A Kitchen Witch’s World of Magical Plants and Herbs is due out this fall and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.

Magical herbology is an area every witch needs to develop competency in, whatever her eventual area of focus. The challenge is to gain more than an abstract knowledge of herbs, to find opportunities for hands-on learning. A Kitchen Witch’s World includes tips on ways to work herbs into your daily life and your magical routine. Over 150 common herbs are covered, which for most witches includes all that will ever be needed. Most of the herbs are easily obtained, although one important herb – mandrake – is hard to find in the United States. (Occult stores will try to sell you mayapple as “American Mandrake” instead.) The entries for each herb are fairly short, but contain a brief description of the plant or its growing habitat, which I believe is important because most beginning witches first encounter these herbs in a package.I think what I like most about this book is that it doesn’t indulge in a plethora of correspondences. The tendency to go overboard with correspondences, to the point where it begins to inhibit learning rather than adding to it, is the bane of beginners – yet correspondences do have an important, necessary role in herb magic. I think this book sets the right balance to a thorny issue.If you already work a good deal with magical herbs, to the point where you have begun growing your own, this book is probably not for you, and if you decide to make this your area of expertise you will outgrow this book in a few years. This is not an encyclopedia, and I think we’ve come to expect the encyclopedic approach to herbs, whether for magic or healing. If you would like to use magical herbs a bit more than you do at present, this would be a good resource to have.A Kitchen Witch’s World of Magical Plants and Herbs is due out this fall and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.

Tag: Pagan Blog Project

Puleew Highway

August 1, 2014

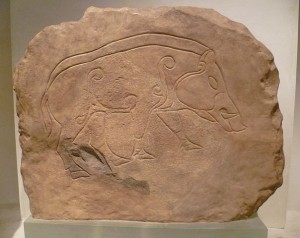

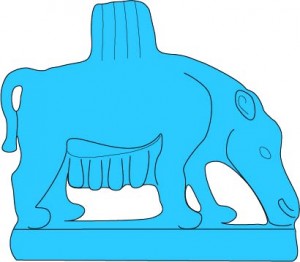

The Old Sow (part 3)

July 25, 2014 The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/

The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/

Oracle

July 18, 2014

Non-Hierarchy in Covens

July 11, 2014

Nut a Sow Goddess?

July 4, 2014

Witchcraft Today: 60 Years On (Review)

June 27, 2014 This anthology, published today, is a look at the major branches of witchcraft that have emerged since the publication of Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today 60 years ago. The branches examined in this book have been heavily influenced by Gardner, reflecting to varying degrees not only the practices of the coven he was initiated into, but Gardner’s own reflections and innovations.The first section of the book explains many of the most popular traditions, while the second section is a collection of personal reflections by practicing witches. There is also a brief biography of Gerald Gardner and a discussion of the climate from which his groundbreaking book emerged. You do not need to have read any of Gardner’s work to follow the articles. This book aims to give an overview of what “witchcraft today” has become and how it has matured.I have written the chapter on Dianic Witchcraft for this anthology. It is not surprising that the Dianic tradition is included here – we usually are mentioned in any overview of Paganism and Witchcraft – but this is the first time to my knowledge that the section on Dianic Witchcraft in an overview has been written by a Dianic priestess. There has been so much misinformation propagated by those outside the Dianic tradition over the years that I think it is an important read not only for women who may be considering finding a Dianic coven, but for all witches. I think this background on Dianic Witchcraft is also important for all feminists, even those who do not consider themselves spiritual. Like it or not, a large part of the battle for women’s rights is occurring within religious institutions and frameworks.Witchcraft Today: 60 Years On is edited by Trevor Greenfield and published by Moon Books. It can be purchased in bookstores or on Amazon.

This anthology, published today, is a look at the major branches of witchcraft that have emerged since the publication of Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today 60 years ago. The branches examined in this book have been heavily influenced by Gardner, reflecting to varying degrees not only the practices of the coven he was initiated into, but Gardner’s own reflections and innovations.The first section of the book explains many of the most popular traditions, while the second section is a collection of personal reflections by practicing witches. There is also a brief biography of Gerald Gardner and a discussion of the climate from which his groundbreaking book emerged. You do not need to have read any of Gardner’s work to follow the articles. This book aims to give an overview of what “witchcraft today” has become and how it has matured.I have written the chapter on Dianic Witchcraft for this anthology. It is not surprising that the Dianic tradition is included here – we usually are mentioned in any overview of Paganism and Witchcraft – but this is the first time to my knowledge that the section on Dianic Witchcraft in an overview has been written by a Dianic priestess. There has been so much misinformation propagated by those outside the Dianic tradition over the years that I think it is an important read not only for women who may be considering finding a Dianic coven, but for all witches. I think this background on Dianic Witchcraft is also important for all feminists, even those who do not consider themselves spiritual. Like it or not, a large part of the battle for women’s rights is occurring within religious institutions and frameworks.Witchcraft Today: 60 Years On is edited by Trevor Greenfield and published by Moon Books. It can be purchased in bookstores or on Amazon.

What are the women’s mysteries?

June 20, 2014

Lady Slipper

June 13, 2014A Lady Slipper is an orchid that grows throughout the northern hemisphere. There are several species, and all of them are rare to uncommon depending on the country. This beautiful orchid is difficult to cultivate, even as orchids go. It requires a special soil fungus for seeds to germinate, and the Lady Slipper does not transplant well. To make matters worse, there is a special demand for this orchid, and not just from gardeners who feel they must have one. The root stock has calming, pain relieving, and hallucinogenic qualities that have prompted overharvesting of the plant, which is never abundant even under ideal circumstances.I have had the good fortune of stumbling across this flower on occasion, ever since I was a girl in Ohio. Last week I was hiking on a popular mountain path when I spied two blooms right next to the trail. I decided to come back early the next day to take a picture, crossing my fingers that no one would arrive before me and take the plants. Sure enough, when I returned the next morning they were gone. I scouted around the area, however, and I found a nice specimen that was slightly better hidden. In researching this post I discovered that one variety of Lady Slipper does indeed look like a shoe. I had always assumed from looking at the flower that the name referred to a different kind of “slipper.” What would you think?

In researching this post I discovered that one variety of Lady Slipper does indeed look like a shoe. I had always assumed from looking at the flower that the name referred to a different kind of “slipper.” What would you think?  Before heading down the mountain with my photographic trophy, I decided to bushwhack to an open ledge for a snapshot of the view, and I came across a whole clump of Lady Slipper plants. There were seven blooms, one for each of the Seven Sisters (Pleiades). These nymph siblings are priestesses of Artemis.

Before heading down the mountain with my photographic trophy, I decided to bushwhack to an open ledge for a snapshot of the view, and I came across a whole clump of Lady Slipper plants. There were seven blooms, one for each of the Seven Sisters (Pleiades). These nymph siblings are priestesses of Artemis.  SourcesGraves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin, 1960.McGhan, Patricia J. Ruta. “Pink ladies slipper (Cypripedium acule Ait.)” US Dept. of Agriculture.

SourcesGraves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin, 1960.McGhan, Patricia J. Ruta. “Pink ladies slipper (Cypripedium acule Ait.)” US Dept. of Agriculture.

Looking at the Sow Goddess

June 6, 2014