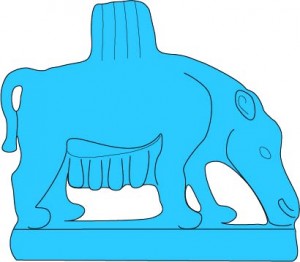

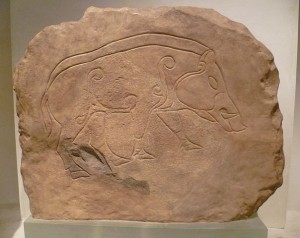

The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/

The third installment of my ongoing saga The Old Sow is now up at Return to Mago blog. Please note that you do not need to read these articles in any order. This series talks about the Sow Goddess, her importance in Neolithic pre-patriarchal cultures in Europe and the Middle East, and her subsequent vilification as patriarchy solidified. There was some discussion after my last article about my assertion that the pig was domesticated about 10,000 years ago. I did not realize that my readers would consider this bit of information interesting, yet alone controversial, or I would have included some sources. Greger Larson, et al, in a 2005 article in Science Magazine place pig domestication at 9,000 years ago while Jean-Denis Vigne, et al, in a paper from the 2009 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say pig domestication could have occurred as early as 13,000 years ago. The Cambridge World History of Food (2000) gives a date of 10,000 years before present. Part of the discrepancy in dates involves the definition of “domestication.” If we define a domesticated animal as one that is commonly raised in captivity for food or work, then earlier dates apply. If an animal that is born in captivity and lives out its life in captivity is considered domestic, then the date of domestication becomes somewhat later. These scenarios reflect the idea of domestication that is most prevalent among journalists and the general public. Archaeologists for the most part have begun defining a “domestic animal” as one that has been selectively bred over a period of time to develop physical features that distinguish it from its wild cousin. This should make it easier to agree on a date, but there have been complications. “Domestic” pigs have often been allowed to forage in the wild, resulting in continuing hybridization between the pig and the wild boar, which was once a common animal with a widespread range. Needless to say, because there are challenges dating the emergence of the domestic pig, there have been disagreements about where the pig was first domesticated (probably in Asia Minor), whether domestication arose independently in different places (considered unlikely, except in Asia Minor and China), and whether pigs were domesticated before or after certain other livestock.I think that it is less important to put a date and an order on domestication of animals than it is to understand 1) that domestication of animals was integral to the development of the type of agriculture needed to support large settled populations and 2) once people got the idea of raising large animals in captivity, they began trying to domesticate many animals that could be a potential food source (usually without success). Since all of this happened so long ago, and since the domestication of animals for food happened quickly, ascertaining the geographic spot and the relative dates is difficult, and even with improved methods of dating, these dates may always be tenuous.SourcesKipple, Kenneth and Ornelas, Kriemhild Conee. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge, UK: The Cambridge University Press, 2000. http://www.cambridge.org/us/books/kiple/hogs.https://community.dur.ac.uk/Larson, Greger, et al. “Worldwide Phylogeography of Wild Board Reveals Multiple Centers of Pig Domestication.” Science Magazine, March 2005. greger.larson/DEADlab/Publications_files/2005%20Larson%20et%20al%20Science.pdfVigne, Jean-Denis, et al. “Pre-Neolithic Wild Boar Introduction and Management in Cyprus More Than 11,400 Years Ago.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752532/

Month: July 2014

Oracle

July 18, 2014

Non-Hierarchy in Covens

July 11, 2014

Nut a Sow Goddess?

July 4, 2014